In a nutshell

As the proportion of women in Turkey with eight rather than five years of education grew, there was a decline in the number of pregnancies and the number of children born per ever-married woman.

As the proportion with eight years of schooling rose, so too did the proportion of women using modern family planning methods and with knowledge of their ovulation cycle.

There is little evidence that schooling changed women’s attitudes towards gender equality.

Economists argue that more educated individuals are more efficient producers of health and more educated parents are more efficient in producing healthy children. Knowledge helps parents make informed decisions about their children’s nutrition and healthcare. It influences health-related behaviours (such as smoking, drug abuse and binge drinking) and lifestyles (such as physical exercise). The health behaviour and lifestyle of parents, particularly mothers, also affects their children’s health (for example, their birth weight).

Parental education is also the most basic component of socio-economic status, which according to epidemiologists is the key determinant of an individual’s health and their children’s health (Adler and Newman, 2002).

Furthermore, education may affect attitudes towards gender equality empowering women (Mocan and Cannonier, 2012). Because mothers are often the primary caregivers for infants and young children, their empowerment is likely to channel family resources more towards the wellbeing of mothers and children.

But economists also quibble over empirical evidence to support these hypotheses. Because genetic endowments are a key determinant of a child’s health, it is challenging to provide convincing evidence that the simple association (correlation) between parental education and children’s health, documented in many studies, implies causality: that parental education improves children’s health.

Arguably, heritable ability may result in more able women seeking higher education and having more able children who have better health (Behrman and Rosenzweig, 2002). Furthermore, future orientation may cause mothers to acquire more education and invest in their children’s health (Fuchs, 1982).

Similarly, establishing causality between mother’s education and early marriage, early childbearing and fertility outcomes is a challenge because low levels of empowerment and high dependency may result in women marrying early and having children, thus forgoing education.

This is an important issue in many Middle Eastern countries where marriage and childbearing in adolescence are high. For example, according to the Turkey Demographic Health Survey 2008, approximately 17% of ever-married women aged 20-45 in Turkey are married before the age of 16, and 13% have a child before they turn 17.

In a recent study, we use a ‘natural experiment’ in Turkey to study the effect of education on women’s fertility, their empowerment and their children’s health (Dinçer et al, 2013).

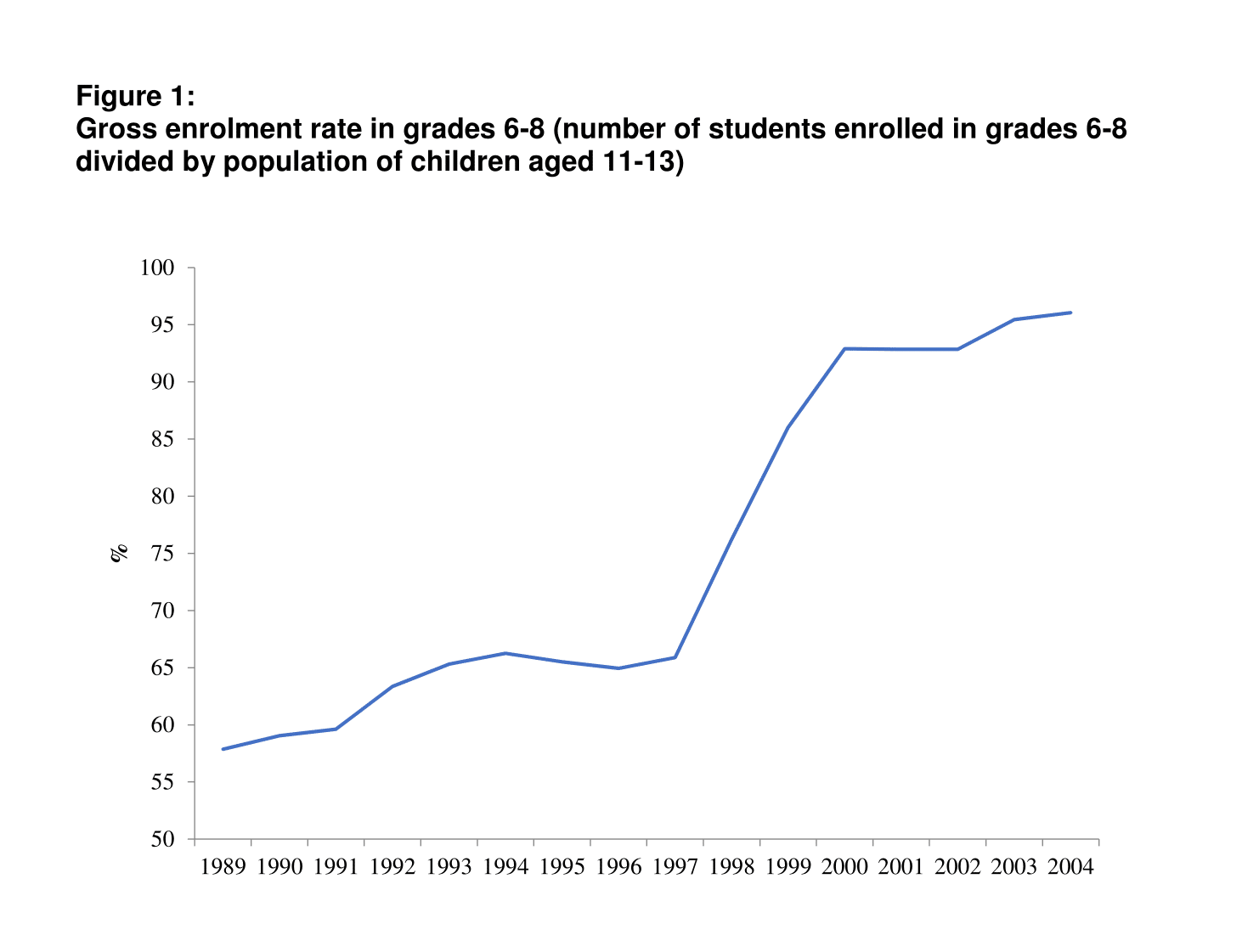

In 1997, Turkey passed the Compulsory Education Law, which increased compulsory formal schooling from five to eight years. Individuals born after 1985 (who were 11 or under in 1997) were the targets of the law – and their rates of enrolment in school in grades 6-8 (ages 11-13) rose (see Figure 1).

To accommodate the expected increase in enrolment, the government devoted additional resources to school infrastructure and hiring new teachers, and these investments varied across the sub-regions of Turkey.

In our experiment, we take a ‘treatment’ group of women who were born between 1986 and 1990 and who were affected by the legislation, and a corresponding comparison group of women who were born between 1979 and 1985 and were not affected.

We take advantage of variations across cohorts in the number of primary school teachers in the sub-region of residence at age 11 to construct an ‘instrument’ that we apply to predict the educational attainment of young women resulting from the Compulsory Education Law.

We then use the predicted education variable to estimate the effect of education on a variety of outcomes experienced by the treatment group of women and their offspring from information obtained when the treatment cohort was between the ages of 18 and 22 and the comparison cohort was between the ages of 23 and 29.

We find that a 10-percentage-point increase in the proportion of ever-married women with eight years of schooling lowered the number of pregnancies per ever-married woman by approximately 0.13 and the number of children born by 0.11. There is also some evidence of a decline in child mortality caused by mother’s education.

Our analysis also shows that a 10-percentage-point increase in the proportion with eight years of schooling raised the proportion of women using modern family planning methods by 8-9% and the proportion of women with knowledge of their ovulation cycle by 5-7%. But we find little evidence that schooling changed women’s attitudes towards gender equality.

From these findings, we infer that the decline in fertility and child mortality that we observe could not be on account of changes in women’s attitudes towards gender inequality resulting from increased education.

It is more likely that the decline in fertility and child mortality are the result of increases in age at first marriage and age at first childbirth, or increased use of contraceptive methods and improvements in women’s understanding of their ovulation cycle. It might be that attitudes are slow to change and that the content of education in classrooms is an important factor when it comes to changing attitudes.

Further reading

Adler, Nancy, and Katherine Newman (2002) ‘Socioeconomic Disparities in Health: Pathways and Policies’, Health Affairs 21(2): 60-76.

Behrman, Jere, and Mark Rosenzweig (2002) ‘Does Increasing Women’s Schooling Raise the Schooling of the Next Generation?’ American Economic Review 92(1): 323-34.

Dinçer, Mehmet Alper, Neeraj Kaushal and Michael Grossman (2013) ‘Women’s Education: Harbinger of Another Spring? Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Turkey’, NBER Working Paper No. 19597.

Fuchs, Victor (1982) ‘Time Preference and Health: An Exploratory Study’, in Economic Aspects of Health edited by Victor Fuchs, University of Chicago Press.

Mocan, Naci, and Colin Cannonier (2012) ‘Empowering Women Through Education: Evidence from Sierra Leone’, NBER Working Paper No. 18016.