In a nutshell

Data on night-light intensity suggest huge destruction in the Syrian economy as a result of the civil conflict.

There is considerable regional variation in the magnitude of destruction, ranging from 18% in Damascus to almost 95% in Idlib.

The destruction has spilled over into neighbouring countries with relatively weak states and institutions, such as Iraq.

The refugee crisis is a growing concern for humanity. According to figures from the United Nations Refugee Agency, one in every 108 people on the planet is ‘displaced’; 20 people were forced to leave their home every minute during 2016, which corresponds to around 29,000 people per day (UNHCR, 2016).

As of today, the total number of displaced people around the world is approximately 70 million. Since the civil conflict began, Syria has been the major country of origin for refugees.

Research on Syrian refugees mostly focuses on the impact of refugee flows on host countries. The main outcomes of interest include employment, wages, consumer prices, housing prices and rents, health status, crime rates, schooling and firm openings in major host countries such as Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. (For some examples, see Tumen, 2016; Balkan and Tumen, 2016; Ceritoglu et al, 2017; Del Carpio and Wagner, 2015; Fallah et al, 2018; and Altindag et al, 2018.)

Developed countries are also concerned with a possible movement of refugees – from either Syria or these primary host countries – towards the West. Governments care about the political economy consequences of refugee inflows. As a result, most of the ‘refugee debate’ in economic research is centred on the wellbeing of natives of host countries.

But with a few exceptions, economists seem to have entirely ignored what has happened in Syria itself. Aside from focusing on the reaction of host countries, this negligence is also due to a lack of systematic and healthy data on the state of the Syrian economy since the conflict began.

We are using data provided by the National Geophysical Data Center of the United States to compare the night-light intensity in Syria before and after the conflict began. Economists have recently started to use night-light data measured by satellites (see, for example, Henderson et al, 2012). The data act as a proxy for local economic activity, exhibiting a strong correlation with other major welfare indicators.

Using the Geographic Information System (GIS) methods adopted in related research, we construct indices combining the contrast and dispersion of night-lights. We report the time series evolution of these indices both for the entire country and at a province level.

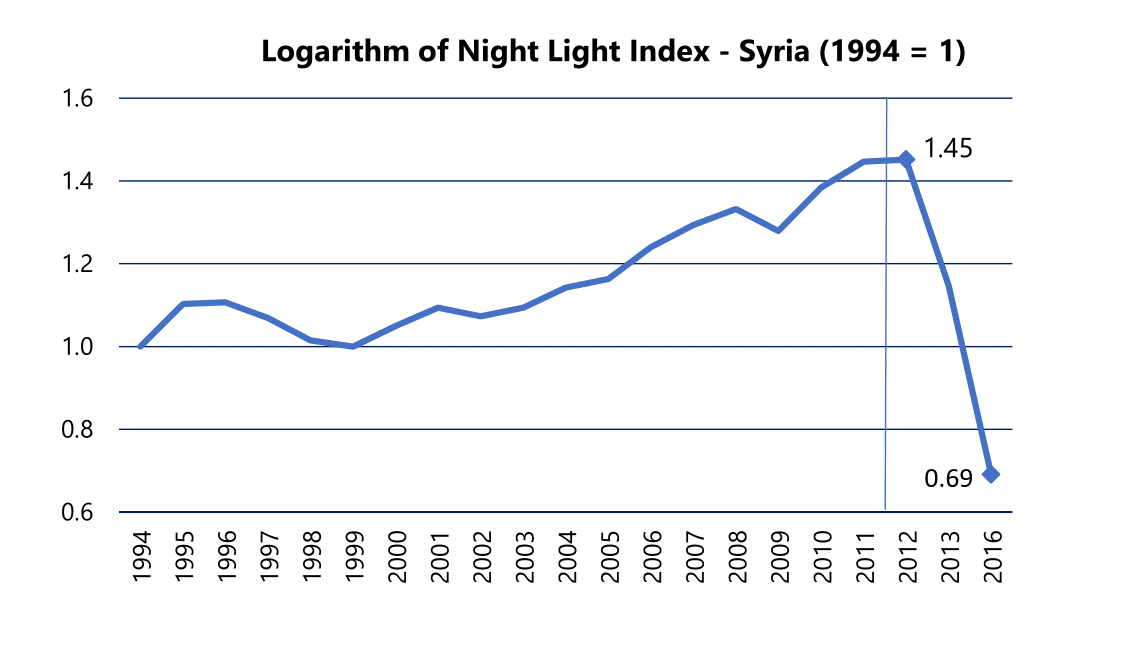

Figure 1 demonstrates the rise and dramatic decline in the aggregate index based on data covering the period from 1994 to 2016. The figure raises three main points:

- First, before the civil conflict, Syrian economy grew – as measured by our index – by approximately 4-5% a year.

- Second, in the post-crisis era (from 2012 to 2016), the magnitude of economic destruction is above 75%.

- Finally, GDP as of 2016 is more than 30% below its level in 1994.

These numbers suggest huge destruction in the Syrian economy as a result of the civil conflict.

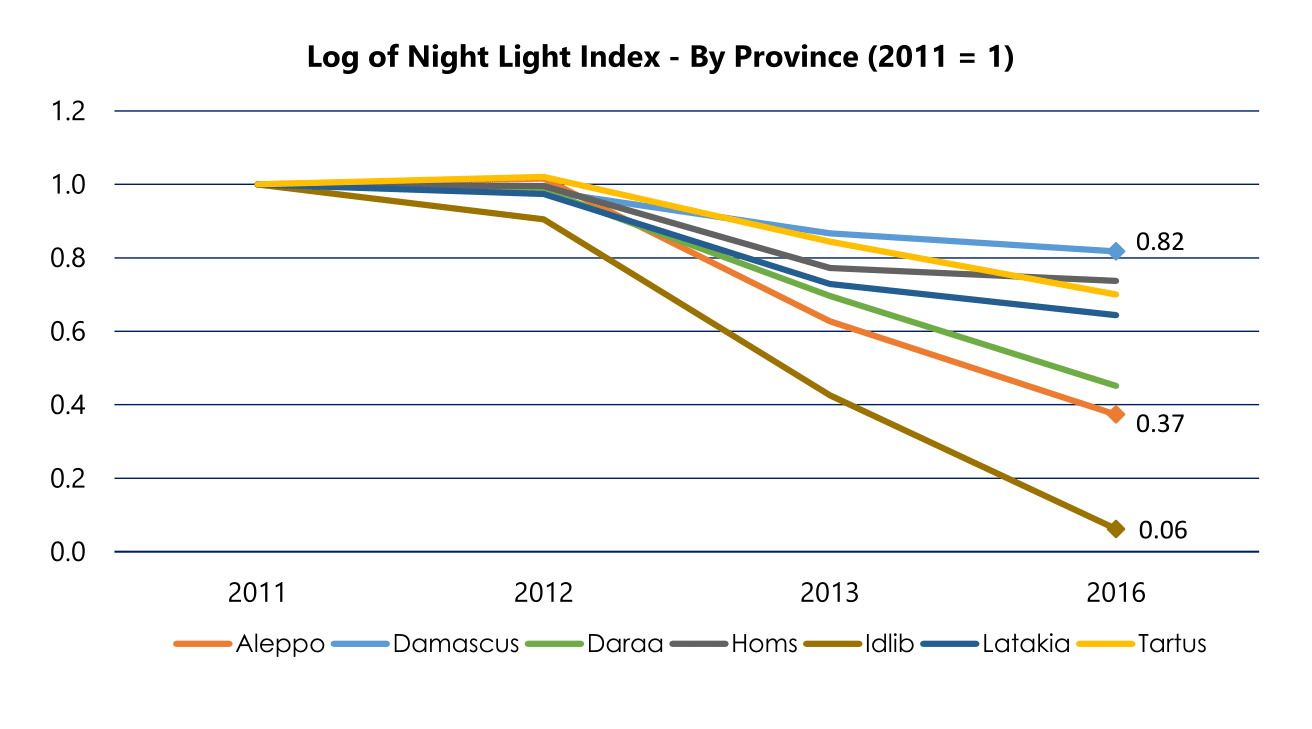

Figure 2 shows the extent of economic destruction in some major Syrian provinces. Clearly, there is considerable regional variation in the magnitude of destruction, ranging from 18% in Damascus to almost 95% in Idlib.

The intensity of violence seems to be an important determinant both in terms of the magnitude of destruction and the volume of refugee outflows. Decline in night-light intensity in provinces such as Idlib, Aleppo and Daraa following the conflict supports this hypothesis. Note that province-level calculations are slightly less reliable than the aggregate figures.

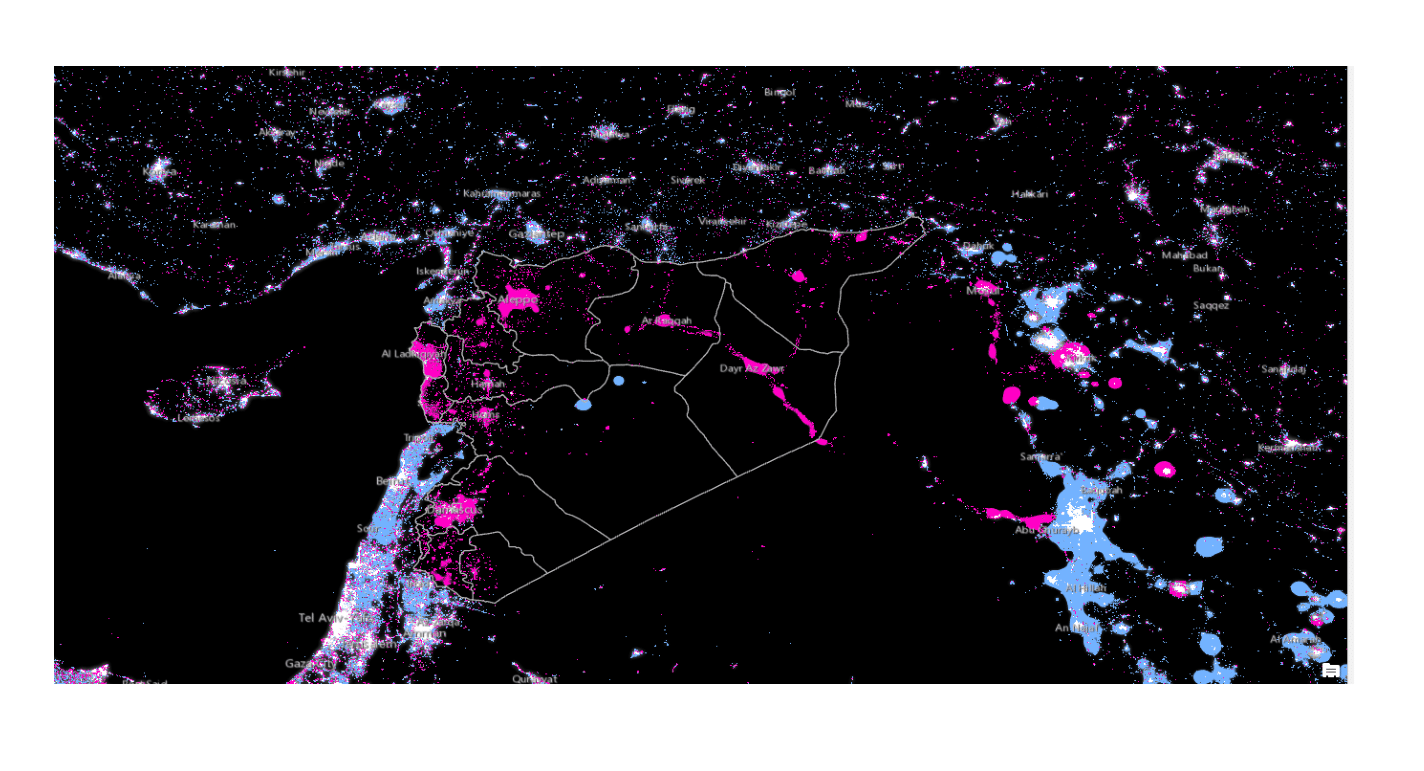

Figure 3 compares the night-light intensity between two years: 2012 and 2016. Pink regions mark the night-lights that existed in 2012 but which had disappeared by 2016. It clearly demonstrates that the crisis has not only severely hit the Syrian economy, but it has also spilled over into Iraq in the form of jihadist terror.

The bottom line is that the civil conflict in Syria has destroyed the economy. The destruction has also spilled over into neighbouring countries with relatively weak states and institutions, such as Iraq.

Current debates about future prospects offer ‘the return of refugees to Syria after the conflict is over’ as a solution to the problems that host countries have been experiencing.

But our calculations suggest that the extent of economic destruction in Syria is so huge that even when the conflict is over, lack of economic opportunity will persist if external assistance to rebuild the country is not provided promptly. Without a strong programme of economic rebuilding, the return of approximately 5.6 million registered refugees to Syria will not happen any time soon.

Further reading

Altindag, O, O Bakis and S Rozo (2018) ‘Blessing or Burden? The Impact of Refugees on Businesses and the Informal Economy’, unpublished manuscript, University of Southern California.

Balkan, B, and S Tumen (2016) ‘Immigration and Prices: Quasi-experimental Evidence from Syrian refugees in Turkey’, Journal of Population Economics 29: 657-86.

Ceritoglu, E, HB Gurcihan-Yunculer, H Torun and S Tumen (2017) ‘The Impact of Syrian Refugees on Natives’ Labor Market Outcomes in Turkey: Evidence from a Quasi-experimental Design’, IZA Journal of Labor Policy 6:5.

Del Carpio, XV, and M Wagner (2015) ‘The Impact of Syrian Refugees on the Turkish Labor Market’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7402.

Fallah, B, C Krafft and J Wahba (2018) ‘The Impact of Refugees on Employment and Wages in Jordan,’ ERF Working Paper No. 1189.

Henderson, JV, A Storeygard and DN Weil (2012) ‘Measuring Economic Growth from Outer Space’, American Economic Review 102: 994-1028.

Tumen, S (2016) ‘The Economic Impact of Syrian Refugees on Host Countries: Quasi-experimental Evidence from Turkey’, American Economic Review 106: 456-60.

UNHCR, United Nations Refugee Agency (2016) ‘Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2016’.

Figure 1:

The Syrian economy 1994-2016, measured by night-light intensity

Source: US National Geophysical Data Center and authors’ calculations.

Note: The index is reported as three-year moving average of the index in natural logarithms. The index measures the intensity of ‘total lights’. 2014 and 2015 data are not publicly available. The vertical line indicates the start of the conflict.

Figure 2:

The extent of economic destruction in major Syrian provinces, measured by night-light intensity

Source: US National Geophysical Data Center and authors’ calculations.

Note: The index is reported as three-year moving average of the index in natural logarithms. The index measures the intensity of ‘total lights’. 2014 and 2015 data are not publicly available.

Figure 3:

Changes in Syria’s night-light intensity between 2012 and 2016

Source: US National Geophysical Data Center and authors’ calculations.

Note: Comparison of the night-light intensity between two years: 2012 and 2016. Pink regions mark the lights that existed in 2012 but which had disappeared by 2016.