In a nutshell

For most developed countries, studies of the impact of automation consistently find negative effects on the labour market; but the net impact of robots on employment and wage changes may be different in developing countries, as well as across industries, skill levels and age groups.

Districts in Turkey with existing manufacturing firms tend to expand employment in response to a robot shock; but robotisation negatively affects the total employment of incumbent workers.

Automation seems to have a complementary relationship with those who keep their employment in the affected firms; this evidence is more apparent when these workers are employed in different occupations within the same firm.

How does automation affect labour markets? Does it simply reduce employment – or does it have additional outcomes, such as creating new job opportunities, increasing productivity, forcing workers to seek employment in different sectors or even to change occupations? There has been a considerable amount of economic research on these important questions.

For example, Graetz and Michaels (2018) demonstrate that between 1993 and 2007, an increase in robot density contributed to a 0.37 percentage point rise in annual GDP growth and a 0.36 percentage point increase in labour productivity growth. Their study finds no significant impact of industrial robots on overall employment levels, although it does report some evidence that they displace low-skilled workers and, to a lesser extent, middle-skilled workers.

Acemoglu and Restrepo (2020) find that in the United States, each additional robot per 1,000 workers is associated with a 0.2% decrease in the employment-to-population ratio and a 0.42% reduction in wages. Equivalently, the addition of one new robot results in a reduction in employment of approximately 3.3 workers. The employment impact of robots is predominantly negative in routine manual and blue-collar jobs, because these workers perform tasks that are easily automated by robots, leading to their displacement.

Conversely, Dauth et al (2018) report no overall employment losses in Germany. But their study differentiates between the manufacturing and services sectors, and while it finds a slightly negative impact on manufacturing employment, there is a positive effect on the services sector. This suggests a potential reallocation mechanism from manufacturing to services.

For most developed countries, studies of the impact of automation consistently find negative effects, either affecting the overall labour market or the manufacturing sector and blue-collar workers specifically. But some studies report positive employment effects. For example, analysing data from EU countries, Klenert et al (2022) find that the use of robots is associated with an increase in manufacturing employment.

Providing evidence from a developing country context, Cali et al (2022) explore the effects of robotisation in Indonesian manufacturing industries and find employment gains. Such studies highlight a mechanism where increased productivity leads to greater scale and higher labour demand. Tuhkuri (2022) finds similar results and explains that in Finland, the positive impact of robotisation on employment is due to firms adopting automation being more likely to focus on making new products rather than displacing labour.

Our new research investigates the relationship between robot adoption and labour market outcomes in Turkey, using novel employer-employee data that includes firm-specific information such as production, wages, trade and worker details provided by the Enterprise Information System of the Ministry of Industry and Technology of Turkey, along with data from the International Federation of Robotics database (Aytun et al, 2023).

Our study analyses labour market outcomes in relation to variations in robot exposure at the district and worker level by considering how sectors and occupation have been affected.

The evolution of robot adoption over recent years

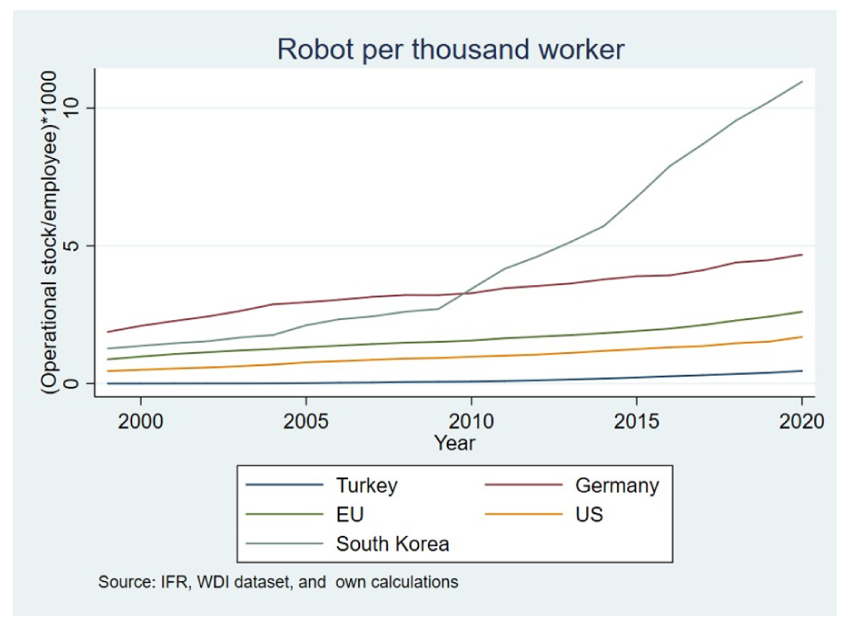

Figure 1 compares the total number of robots per 1,000 workers among selected leading countries and the EU. There is a general upward trend for all, but considerable variations between countries. South Korea experienced a sharp increase in robot penetration per 1,000 workers after 2010, achieving the highest rate of robot adoption. In contrast, Turkey has the lowest penetration rate and has seen only a slight increase during the same period.

Figure 1: Robot stock per 1,000 workers, 1999-2021

Source: Aytun et al (2023)

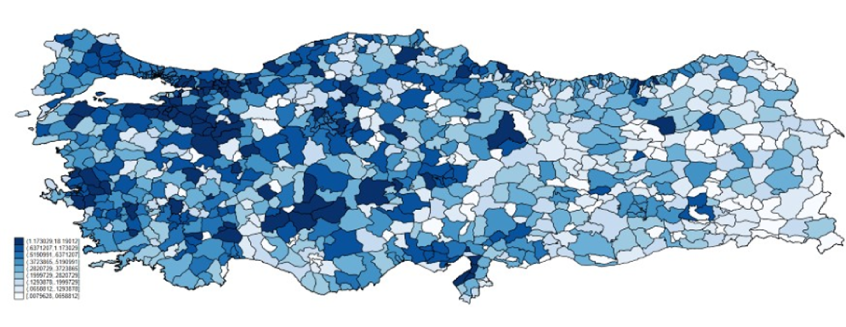

Figure 2 illustrates the robot exposure index developed by Acemoglu and Restrepo (2020). The figure demonstrates that the level of exposure closely mirrors the industrialisation levels of districts in Turkey. Western regions tend to have higher employment in manufacturing industries, while eastern regions are more focused on agriculture and services.

Given that the robot industry is primarily concentrated in the automotive and electronics sectors, this specialisation is directly reflected in the exposure index. The Marmara region in the northwest, along with Aksaray and Kirikkale – highlighted as the boldest regions in central Turkey – are prime examples of this trend.

Figure 2: Robot exposure of Turkey, all industries

Source: Aytun et al (2023)

Robots and the workplace

Developing countries often exhibit inefficiencies in their production processes. This indicates the potential for average productivity gains from using robots to generate demand for more workers.

We first test this hypothesis by analysing data from firms operational since 2014, finding that districts with existing firms tend to expand employment in response to a robot shock. But null effects of robot exposure are also found.

Second, we look at how workers in the manufacturing industry adjust their employment and wages when they are exposed to robots. Our results reveal that robotisation negatively affects the total employment of incumbent workers.

This effect is mainly for workers who stay at their original workplace. In other words, the likelihood of keeping the same employment in a non-manufacturing industry reduces when incumbents face exposure to robots. Staying at the original firm and manufacturing industry is also negatively affected by robotisation. But the earnings of the former group are improved in industries with higher robot exposure.

This finding confirms that automation has a complementary relationship with those keeping their employment in the original firm. This evidence is more apparent when these workers are employed in different occupations within the same firm.

Further reading

Acemoglu, D, and D Autor (2011) ‘Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings’, in Handbook of Labor Economics 4: 1043-1171, Elsevier.

Acemoglu, D, and P Restrepo (2020) ‘Robots and jobs: Evidence from US labor markets’, Journal of Political Economy 128(6): 2188-2244.

Aghion, P, C Antonin, S Bunel and X Jaravel (2020) ‘What are the labor and product market effects of automation? New evidence from France’.

Autor, D, F Levy and RJ Murnane (2003) ‘The skill content of recent technological change: An empirical exploration’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4): 1279-1333.

Aytun, U, Y Kılıcaslan, O Mecik and Ü Yapıcı (2023) ‘Robots, Employment and Wages: Evidence from Turkish Labor Markets’, ERF Working Paper No 1696.

Calì, M, and G Presidente (2021) ‘Automation and manufacturing performance in a developing country’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 9653.

Dauth, W, S Findeisen, J Suedekum and N Woessner (2021) ‘The adjustment of labor markets to robots’, Journal of the European Economic Association 19(6): 3104-53.

Frey, CB, and MA Osborne (2017) ‘The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114: 254-80.

Graetz, G, and G Michaels (2018) ‘Robots at Work’, Review of Economics and Statistics 100(5): 753-68.

Griliches, Z (1969) ‘Capital-skill complementarity’, Review of Economics and Statistics 51(4): 465-68.

Keynes, JM (1930) ‘Economic possibilities for our grandchildren’, in Essays in Persuasion: 321-32, Palgrave Macmillan.

Klenert, D, E Fernandez-Macias and JI Anton (2023) ‘Do robots really destroy jobs? Evidence from Europe’, Economic and Industrial Democracy 44(1): 280-316.

Tuhkuri, J (2022) ‘Essays on Technology and Work’ (doctoral dissertation, MIT).