In a nutshell

The health and economic performances of countries during the pandemic map closely to ‘trust in government’ as measured before the onset of the health crisis: countries with high levels of trust tend to perform better on both health and the economy.

In the case of the Arab world, there are over- and under-achievers: trust in government could go up for countries that over-achieve, and down for those that under-achieve, in relation to their pre-crisis levels of trust, making their future challenges more solvable.

Coming out of the Covid-19 crisis, the future for all Arab countries looks starker. In the short-term, the main challenge will be the unavoidable austerity to come: trust can help in distributing losses in society without generating high levels of discontent.

Societies across the Arab world were already facing historical challenges before the Covid-19 pandemic struck. Their economies were hit by a massive oil shock in 2015 (coming on the heels of an equally massive oil boom) and their autocratic mode of governance was in crisis after the 2011 Arab Spring (especially in Egypt, Libya, Syria, Tunisia and Yemen) and its aftershock in 2019 (especially in Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon and Sudan).

Calls for renewed ‘social contracts’ and ‘economic diversification’ had become commonplace before the virus hit. At issue is the nature of the relations between state, society and business. At the risk of caricaturing a complex picture, the unwillingness of autocrats to open up the economy to private (and more autonomous) businesses has bled the economy, pushing society to rebel.

At such critical junctures, small differences in circumstances can make a big difference for the path a society takes. Here comes Covid-19. With lives threatened, public policy became a matter of national security. The response is as complex as war – it involves all parts of the state and affects the entire population. As some have described the pandemic, it is a ‘stress test’ for the whole system. Along with evidence-based and sound public health strategies, national solidarity and individual sacrifice are required to stop the spread of the virus.

Politically, Covid-19 did manage to stop the second Arab Spring, for now. But this is at best a short reprieve. How each country comes out of the pandemic will define the momentum with which it can start addressing its own structural challenges – economic, social and political.

In particular, countries that are able to manage the Covid-19 crisis successfully could end up with sufficient levels of national trust to help address more ambitious collective challenges. Indeed, in the case of Kerala (a state in southwest India), trust in government, especially in the context of good governance, was reinforced after the public authorities pro-actively responded and successfully contained the ‘first wave’ of the pandemic (Jalan and Sen, 2020).

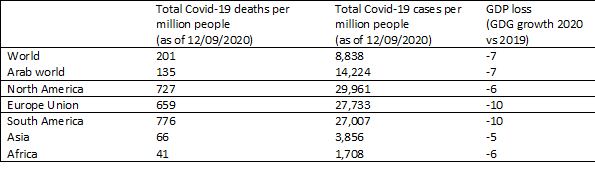

There is a common view that managing Covid-19 is all about making a trade-off between lives and livelihoods (Diwan and Abi-Rached, 2020). But comparing global performance on health and on economics does not support this view (see Table 1). Countries and regions have tended to do well, or not, on both fronts simultaneously.

At the global level, we find that a key correlate of a successful country performance is a high level of ‘trust in government ‘ or TG (measured in the Middle East and North Africa by the Arab Barometer). A higher level of TG makes compliance with public health and social measures more efficient and therefore minimises economic casualty (more on this below).

The Arab world generally performed fairly well when compared with other regions. Through a ‘combination of luck and skill’, it was spared very high rates of mortality and morbidity during the first wave, although recently it has started to move closer to the rest of the world (Beschel and Youssef, 2020).

The Arab world still falls close to the world average on both health and economic performances – worse than Asia, but better than the rich West and Latin America.

Table 1. Global comparison of health and economic performances

Source: Our World in Data for Covid-19 mortality and cases and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) World Economic Outlook 2020 for GDP point losses.

This is somewhat hopeful. But there is significant variation within the region, suggesting that the future may be one of divergence among countries.

Health performance

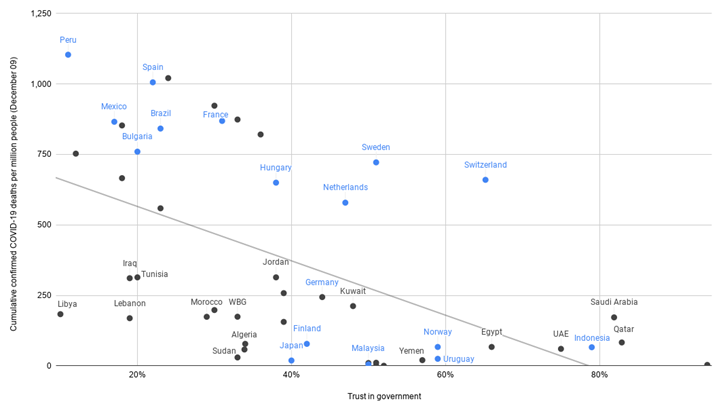

On the health side, broadly speaking, there are four categories of countries (see Figure 1):

Countries that have performed worse than the world average

These include Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman and Tunisia. The reasons for such poor performance are various. Iraq, for example, the worst performing country in the Arab world, is experiencing an unprecedented breakdown of both society and state. Not only is the healthcare system in total shambles, but the state is also unable to enforce either lockdown or other public health measures, such as mask wearing or social distancing (The Economist, 2020).

Countries that have overdone social and mobility measures while failing to protect vulnerable groups

The countries within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have tended to overdo the stringency and length of the mobility restrictions (as measured by Our World in Data). Despite strict measures, they did not manage to protect migrants sufficiently (Bahrain, Kuwait and Oman have a high number of Covid-19 deaths per million people, above the world average). Some ended up with some of the highest Covid-19 infection rates in the world (Qatar has a staggering 50,000 cases per million people, five times the world average).

Countries that have tried to manage the spread of the virus closely, with variations in lockdown intensity over time

Some of the countries that have opted for this ad hoc approach in the absence of a comprehensive strategy have succeeded better than others when they were able to provide sufficient social safety nets to vulnerable groups and adequate economic relief to businesses. In order of decreasing performance, these are: Algeria, Egypt, Lebanon and Morocco. Algeria and Egypt may have used Covid-19 to quell protests, given that the stringency of the public health measures was disproportionate to the number of cases and fatalities in the two countries (for Algeria, see Serrano, 2020; for Egypt, see Human Rights Watch, 2020).

Countries with unreliable institutions

In several countries with continuing civil strife or emerging from war, and where institutions are notoriously unreliable, the data are likely to be extremely unreliable and one cannot assess what truly happened. These include Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

Figure 1: Health performance and trust in government

Sources: Our World in Data for Covid-19 mortality; World Value Survey (wave 7) and Arab Barometer (wave 5) for Trust in Government (‘how much do you trust government,’ we retained the percentage for a great deal or quite a lot). R2 is 0.3.

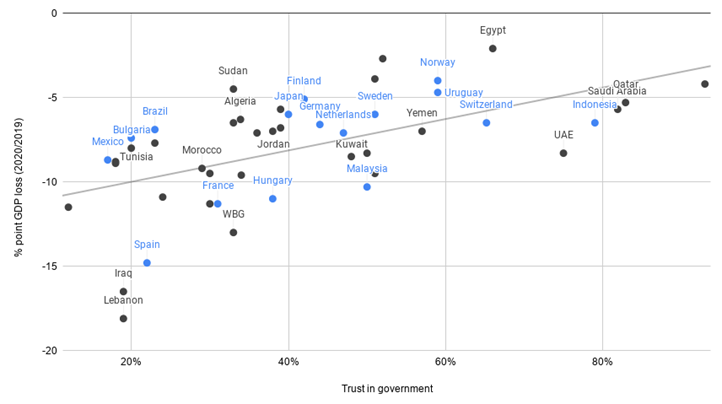

Economic performance

Economically, countries that are more exposed externally have suffered more – with reduced tourism, remittances, oil revenues and foreign direct investment, and more costly debt refinancing. But equally, countries with poor health performance, and those that had to impose tight closures of the economy repeatedly, suffered additionally from deeper internal shocks (Figure 2):

Lebanon and Iraq, which were already in crisis, collapsed (around a 20 percentage point GDP loss) while the West Bank and Gaza was badly hurt (a 12 percentage point GDP loss).

Some GCC countries (Kuwait, Oman and the UAE), Morocco and Tunisia have had world average performances with between a 7 and 10 percentage point GDP loss.

The best achievers (less than a 7 percentage point GDP loss) include Egypt (-2 percent), Algeria, Bahrain, Jordan, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. (Also, Sudan and Yemen, but only because they experienced a large fall in GDP in 2019).

Figure 2. Economic performance and trust in government

Sources: IMF (change in real GDP growth between 2019 and 2020), World Value Survey (wave 7) and Arab Barometer (wave 5) for Trust in Government (‘how much do you trust government,’ we retained the percentage for a great deal or quite a lot). R2 is 0.312

Trust in government

As is evident in Figures 1 and 2, health and economic performances map closely to TG (as measured before the onset of the health crisis) in the global sample. Countries with high TG levels tend to perform better on both health and the economy.

In the case of the Arab world, however, there are over- and under-achievers. Given Kerala’s experience of a virtuous cycle of trust-building, one can hence speculate that the TG figures could go up for countries that over-achieve, and down for those that under-achieve, in relation to their pre-crisis TG levels, making their future challenges more solvable.

In particular we can identify three groups given their TG levels:

High trust in government

GCC countries had high TG levels going into the crisis and, instead of performing well, some under-achieved on both health and the economy compared with countries at similar levels of TG (for example, Indonesia). Egypt, which also had relatively high TG, performed well on the economic front, but less so on health (when compared, for example, with Uruguay).

Medium trust in government

Algeria, Jordan and Morocco have medium TG levels, and they all over-performed compared with countries at similar TG levels (for example, France or Hungary). This could create positive momentum for future reforms.

Low trust in government

In the low TG level countries, the results are rather surprisingly favourable: while their performances are worse than global averages, they tend to be better than those of countries at similarly low levels of TG.

In that sense, Tunisia over-performed on both economic and health (for example, compared with Bulgaria) and while Lebanon and Iraq under-performed on the economy (where crises were brewing before the arrival of Covid-19), they both over-performed on health (compared, for example, with Mexico, Spain and other countries with similar TG levels).

This may create positive momentum though the situation is complex in these countries, with some currently facing a multitude of crises, including unprecedented socio-economic crises (for Lebanon, see Abi-Rached and Diwan, 2020). Moreover, questions have been raised about the accuracy of the data given fear, stigmatisation, weak institutions and lack of surveillance systems (for Iraq, see United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq, 2020).

Looming austerity

Coming out of the Covid-19 crisis, the future in all the countries of the Arab region looks starker. In the short term, the main challenge will be the unavoidable austerity to come. Trust can help in distributing losses in society without generating high levels of discontent.

Social stress is acute in countries already in the middle of an economic crisis (Lebanon, Sudan and Yemen). And it is rising in countries where the fiscal space is closing rapidly. The list is growing and includes: Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco, Oman, Tunisia and countries where public and/or external debt ratios are fast reaching unsustainable levels (International Monetary Fund, 2020).

The medium-term challenge of diversifying the economy away from oil and creating good jobs is even more difficult. The central trade-offs on this front are largely political. Rather than just thinking about what goods can be produced, the real question is whether the political system is willing to free up the private sector, where the opposition may hide, and allow for ‘creative destruction’, including among firms that are closely allied with ruling regimes (see Diwan et al, 2020).

The task will be especially complex for the oil exporters and for the regimes that have not started to open up.

Further reading

Abi-Rached, Joelle M., and Ishac Diwan (2020) ‘The Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19 on Lebanon: A Crisis Within Crises’, The European Union and the European Institute of the Mediterranean, June.

Beschel, Robert P. and Tarik M. Youssef (2020) ‘The Middle East and North Africa and Covid-19: Gearing up for the long haul’, Brookings, 13 December.

Diwan, Ishac, and Joelle Abi-Rached (2020) ‘Killer Lockdowns’, The Forum, ERF.

Diwan, Ishac, Adeel Malik and Izak Atiyas (eds) (2019) Crony Capitalism in the Middle East: Business and Politics from Liberalization to the Arab Spring, Oxford University Press.

The Economist (2020) ‘Iraq Is Too Broken to Protect Itself from Covid-19’, 3 October.

Human Rights Watch (2020) ‘Egypt: Covid-19 Cover for New Repressive Powers’, 7 May.

International Monetary Fund (2020) Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East and Central Asia.

Jalan, Jyotsna, and Arijit Sen (2020) ‘Containing a Pandemic with Public Actions and Public Trust: The Kerala Story’, Indian Economic Review, 28 July: 1-20.

Serrano, Francisco (2020) ‘In Algeria, Protests Pause for COVID-19 as the Regime Steps Up Repression’, World Politics Review, 31 August.

United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (2020) ‘COVID-19: Putting Numbers in Perspective – Iraq’, ReliefWeb, 3 April.