In a nutshell

Firms in Egypt with more educated and more experienced managers are more likely to operate with a checking account, which is often a prerequisite for obtaining credit.

There is evidence of crowding-out: firms located in areas with a greater presence of banks that heavily invest in government debt are more likely to be credit-constrained.

Financially excluded firms are less likely to invest: it may well be that lack of access to external finance prevents some profitable investment opportunities from being realised.

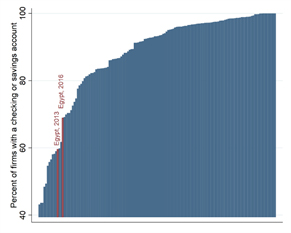

Access to finance in Egypt is characterised by two salient features. First, account penetration is structurally low. Egypt is a ‘cash economy’ and, as Figure 1 illustrates, even among registered firms, less than 70% had a checking account in 2013 and 2016 (60% and 69%, respectively).

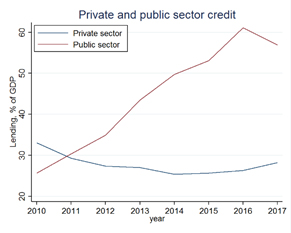

Second, credit supply has exhibited considerably cyclical variation over the past decade. Figure 2 shows that the share of public debt in the balance sheets of banks increased substantially after 2011. At the same time, the government’s overdraft with the central bank increased from 6% of GDP in 2010 to a peak of 22% in 2016, indicating that the domestic banking system was not able to accommodate the refinancing needs of the government.

In a recent study (Betz et al, 2019), we explore structural and cyclical aspects of access to finance using unique data on the location of firms and bank branches in Egypt. The structural level of our analysis looks at whether a firm has a checking account and why. At the cyclical level, we examine whether the firm is able to obtain credit when it needs it, using a standard measure of credit constraints.

Our study uses firm-level data from the Middle East and North Africa Enterprise Survey, which provides representative samples of the formal private sector in several MENA economies. For Egypt, panel data on 600 firms that answered the same questionnaire in 2013 and 2016 are available. The availability of panel data mitigates the concern that our findings are an artefact of the exceptional environment prevailing in the aftermath of the Arab Spring.

Figure 1. Account penetration in Egypt and around the world, by country

Source: Enterprise Surveys.

Figure 2. Government borrowing from local banks in Egypt in 2010-2017

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Central Bank of Egypt.

Consequences of remaining unbanked: lower employment growth and less investment

Small and medium-sized enterprises trade off the costs and benefits of participating in the financial system. The decision to open a checking account is similar to the decision to register a company. Access to credit is valuable for firms with substantial growth opportunities, while the costs can consist of taxes, licensing requirements and social insurance contributions (Kenyon, 2008; Straub, 2005).

A checking account is important for access to finance because it allows a bank to monitor inflows and outflows and thereby reduces the information asymmetries that plague lending to small firms. In particular, account information helps the bank to establish reliable turnover and cash flow figures, which in turn is crucial for creating rudimentary financial statements (Munro, 2013).

Banks are therefore likely to withhold financing from a borrower that operates on a cash-only basis. But routing transactions through the checking account also comes at a cost for the firm because it can become more difficult to hide revenues from tax authorities. The costs of having a bank account are likely to be higher if the intermediation capacity of the banking system is weak and the likelihood of being credit-rationed is high.

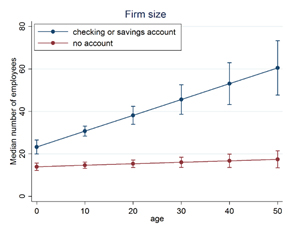

We find that firm size is strongly associated with having a checking account. Figure 3 plots the median number of employees conditional on age for firms in the MENA region. While old firms with an account tend to be larger than young firms with an account, unbanked firms remain small, regardless of age. The figure is also in line with previous evidence showing that an average firm grows faster in the United States than in Mexico or India, where financial systems are less developed (Hsieh and Klenow, 2014).

Our analysis provides some insights as to why financially excluded firms remain small:

- First, financially excluded firms are less likely to invest. Whereas 17% of firms with an account purchased fixed assets in the previous financial year, only 11% of the unbanked firms did.

- Second, 73% of firms with an account fund their investments exclusively from internal sources, compared with 90% of financially excluded firms. It may well be that lack of access to external finance prevents some profitable investment opportunities from being realised.

Figure 3. Median number of employees, by firm age and account status

Source: Authors’ calculations using MENA Enterprise Survey.

Note: The figure reports predictions from a linear quantile regression net of year and industry fixed effects.

Human capital of the manager supports financial inclusion

The extent to which financial exclusion has opportunity costs in terms of lost firm growth is likely to depend on entrepreneurial skill (La Porta and Shleifer, 2014; Gennaioli et al., 2013). Indeed, our results show that Egyptian firms with a more educated and more experienced manager are more likely to obtain an account. In addition, firms that operated informally before registering are less likely to open an account.

We also provide evidence that entrepreneurial human capital matters because of firm quality rather than financial literacy. Firms run by more educated managers are more likely to have a website, to innovate and to have expansion plans.

At the same time, however, we do not find evidence that local intermediation capacity provides incentives for firms to engage with the banking system. Our study considers three different measures of credit supply and one measure for a demand shock. In particular, the share of firms with a bank account or with a loan outstanding in the neighbourhood of the respondent, and a measure of crowding out are not strongly associated with the decision to open a bank account.

Similarly, a negative liquidity shock coming from losses due to spoilage, a power outage or a request for a bribe from a government official cannot explain financial inclusion. It appears likely that in times of need, unbanked firms turn to informal providers of finance.

Firms with a bank account can be credit-constrained due to crowding-out

In addition to the structural dimension, we consider how the intermediation capacity of the banking system varies over the business cycle. In particular, we look at whether a firm is credit-constrained. Credit-constrained firms fall in one of two categories:

- Firms that applied for a loan and were rejected.

- Firms discouraged from applying either because of unfavourable terms and conditions or because they did not think the loan application would be approved. The terms and conditions that discourage firms include high collateral requirements, complex application procedures, unfavourable interest rates and insufficient size of loan and maturity.

To measure cyclical variation in credit supply, we construct a crowding-out index that exploits information on the location of firms and bank branches, as in Betz and Ravasan (2016) and Popov and Udell (2012). A firm that is surrounded by branches of banks that invest more in government debt will score high on the crowding out index. The idea is that firms located in the vicinity of banks that rapidly increased their government debt holdings are more likely to be financially constrained.

We find that crowding-out reduces credit supply: firms located in areas with a greater presence of banks that increase their holding of government debt are more likely to be credit-constrained. Our results also show that firms with a more educated and more experienced manager are less likely to be credit-constrained, while firms that operated informally before registering are more likely to be credit-constrained.

Conclusion and policy implications

Following the outbreak of Covid-19, public spending in Egypt is projected to increase to cushion the negative impact of the pandemic on the economy. Higher refinancing needs, combined with heightened risk aversion among investors, may drive up interest rates and crowd out lending to the private sector. The authorities need to take account of the implications for the intermediation capacity of the banking system and the financing conditions of the private sector.

While crowding-out affects the supply of loans to firms that have a bank account, it does not have a strong impact on the structural issue of the large share of firms that are completely disconnected from the financial sector, in good and bad times of the economic cycle. Instead, reforms to improve the business environment and managerial skills, which in turn increase the opportunity costs of remaining unbanked, can also support financial inclusion.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Investment Bank.

Further reading

Betz, F, and FR Ravasan (2016) ‘Collateral regimes and missing job creation in the MENA region’, EIB Working Paper 2016/03.

Betz, F, FR Ravasan and CT Weiss (2019) ‘Structural and cyclical determinants of access to finance: Evidence from Egypt’, EIB Working Paper 2019/10.

Gennaioli, N, R La Porta, F Lopez-De-Silanes and A Shleifer (2013) ‘Human capital and regional development’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(1): 105-64.

Hsieh, C-T, and PJ Klenow (2014) ‘The life cycle of plants in India and Mexico’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(3): 1035-84.

Kenyon, T (2008) ‘Tax evasion, disclosure, and participation in financial markets: Evidence from Brazilian firms’, World Development 36(11): 2512-25.

La Porta, R, and A Shleifer (2014) ‘Informality and development’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(3): 109-26.

Munro, D (2013) A Guide to SME Financing, Palgrave Macmillan.

Popov, A, and GF Udell (2012) ‘Cross-border banking, credit access, and the financial crisis’, Journal of International Economics 87(1): 147-61.

Straub, S (2005) ‘Informal sector: The credit market channel’, Journal of Development Economics 78(2): 299-321.