In a nutshell

Disruptions to three of Egypt’s big foreign income sources – tourism, the Suez Canal and remittances from Egyptians working abroad – will have far-reaching implications.

If the crisis persists for three to six months, the cumulative loss from these three external shocks alone could amount to between 2.1% and 4.8% of GDP in 2020.

While the country’s focus currently is rightly on fighting the health crisis and mitigating its immediate impacts, planning on how to re-open the economy should start now.

The economic impacts of the Covid-19 crisis are increasingly hitting low- and middle-income countries and the poor. International travel restrictions and the full or partial closure of businesses and industries in Asia, Europe and North America have led to a collapse in global travel and are expected to reduce the flows of remittances. Tourism and remittances are important sources of employment and incomes for the poor, respectively. In what follows, we assess the potential impacts of the expected reductions in these income flows by using Egypt as a case study.

The pandemic is likely to have a significant economic toll. For each month that the Covid‑19 crisis persists, our simulations using IFPRI’s Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) multiplier model for Egypt suggest national GDP could fall by between 0.7% and 0.8% (EGP 36-41 billion or $2.3-$2.6 billion). Household incomes are likely to fall, particularly among the poor.

Egypt is a rising star among emerging economies. Even though several reforms remain to be completed, the reform programme launched in 2016 has started to bear fruit: Egypt has achieved economic growth of over 5% in the last two years. The tourism sector recorded its highest revenues in 2018-19, another sign of increased stability. Continued efforts aimed at improving Egypt’s business climate were expected to lead to even stronger private sector growth and economic diversification in 2020 and beyond.

This progress will almost certainly be interrupted by the Covid‑19 pandemic. While the government is taking actions to contain the spread of the virus (including the suspension of commercial international passenger flights, school and sports clubs closures and a nationwide night-time curfew) and the number of reported infections in Egypt is currently low compared with that of many other countries, the global economic slowdown is expected to have major knock-on effects for Egypt.

International travel restrictions are already curtailing tourism to the country. The global slowdown is likely to be reducing payments received from the Suez Canal and remittances from Egyptians working abroad. These three sources together account for 14.5% of Egypt’s GDP. Thus, any disruptions to these foreign income sources will have far-reaching implications for Egypt’s economy and population.

Using the SAM multiplier model for Egypt, we simulate the individual and combined effects of a collapse in the tourism sector and reductions in Suez Canal revenues and foreign remittances under more and less pessimistic scenarios. SAM multiplier models are well suited to measuring short-term direct and indirect impacts of unanticipated, rapid-onset demand- or supply-side economic shocks such as those caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. We model the demand shocks as the anticipated reductions in tourism, Suez Canal and remittances revenues.

Our results show the potential significant impact on the economy and people for each month that the Covid-19 crisis persists. If the dynamic effects of the Covid-19 shock on the Egyptian economy are different than those simulated, our results could be either under- or over-estimations of the aggregate economic impact of the crisis. Also, effects from other channels may reinforce the effects of the pandemic.

These expectations also assume that there is no change in the current government policies in place to combat the crisis. This is important to note, as the government is taking aggressive action to contain the disease and support the economy and people. As such, the model scenarios do not consider the impacts of specific government economic policies, but are intended to support government decision-makers in deciding on the scale of their support to the economy and Egyptian households.

Figure 1 breaks down estimated losses in GDP, which may hit 0.8% per month in the more pessimistic scenario. Lower tourist spending will affect not only hotels, restaurants, taxi enterprises and tourist guides, but also food processing and agriculture. Lower public revenues from Suez Canal fees are likely to affect the government budget. Lower remittances income will be likely to reduce household consumption of consumer goods and hit sectors producing intermediate goods.

We estimate that the absence of tourists alone may cause monthly losses of EGP 26.3 billion, or $1.5 billion. Thus, the loss in tourism revenues accounts for about two thirds of the total estimated impact.

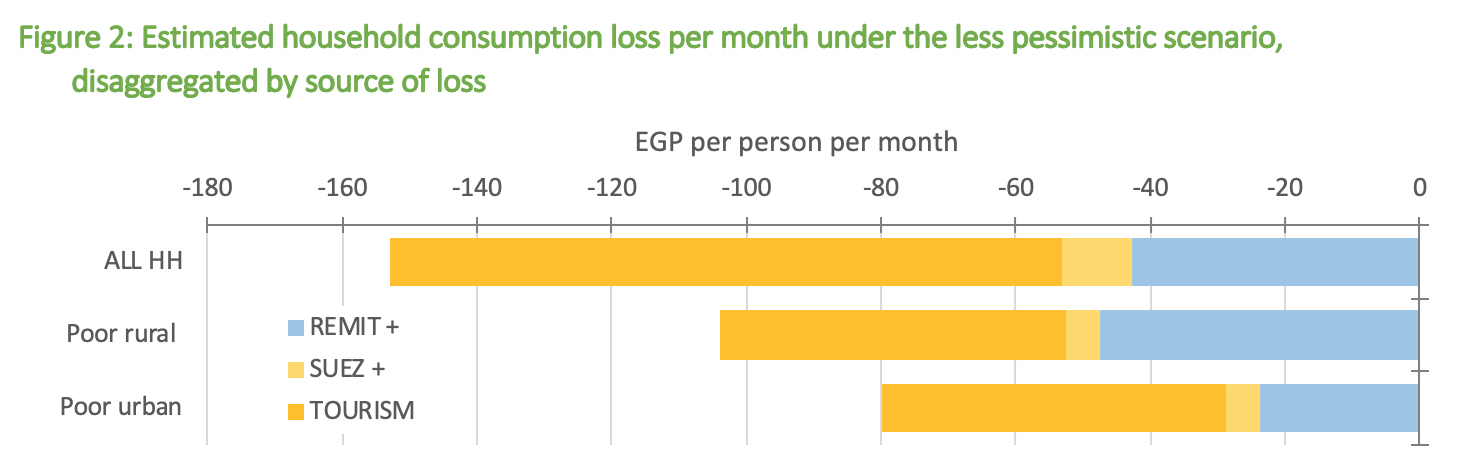

Household incomes are estimated to decline by between EGP 153 or $9.70 (less pessimistic scenario) and EGP 180 or $11.40 (more pessimistic scenario) per person per month for each month that the crisis continues (between 9.0% and 10.6% of household income).

The expected reduction in tourism has the strongest effect on all households, making up more than half the economic impact for all household types in the model (Figure 2). Households are also affected directly and indirectly by lower remittances from abroad.

While all households are hurt by lower tourist expenditures, it is poor households – and especially those in rural areas – that suffer the most from lower remittances. Due principally to the relatively greater decline in remittances that they experience, rural poor households are estimated to lose in total between EGP 104 and 130 ($6.60-$8.20) per person per month, or between 11.5% and 14.4% of their average income, while urban poor households will see their incomes decline somewhat less, between EGP 80 and 94 ($5-$6) per person a month, or between 9.7% and 11.5% of their average income.

Policy considerations

If the crisis persists for three to six months, as many now believe likely, the cumulative loss from these three external shocks alone could amount to between 2.1% and 4.8% of GDP in 2020. Importantly, our simulations measure only the effects that might result from specific impact channels – for example, foreign sources of remittances and revenues.

Domestically, restrictions on movement of people and goods within the country and on certain productive activities may also have adverse economic impacts. On the other hand, some sectors may benefit, such as information and communications technologies, food delivery or the health-related goods and services sectors.

The authorities have begun a course of decisive action to curb the virus outbreak by allocating EGP 100 billion ($6.3 billion) and have enacted tax breaks for industrial and tourism businesses, reducing the cost of electricity and natural gas to industries, and cutting interest rates, and is considering providing grants to seasonal workers.

Additional measures may also be in the works, such as increasing cash transfer payments to poor households, increasing unemployment benefits and providing targeted support to specific sectors.

While the country’s focus currently is rightly on fighting the health crisis and mitigating its immediate impacts, planning on how to re-open the economy should start now. To emerge stronger after the Covid-19 crisis, both the public and private sectors should continue to strengthen their collaboration. The government should work to improve further the business climate for the private sector and continue undertaking serious reforms to overcome institutional weaknesses.

The crisis may also provide an opportunity to strengthen analytical capacity in Egypt to provide policy-makers with research-based solutions for safeguarding Egypt’s economy during future pandemics and other crises.

Unless governments around the world take decisive action, the case of Egypt suggests that poverty is likely to increase in countries where tourism and remittances play a large role. It is also a strong reminder of the interconnectedness of the world and the importance of global cooperation to end this crisis and to be better prepared for the future.

This column was first published by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) – see original version.