In a nutshell

Syrian refugees in Jordan are a predominantly young population in need of substantial support: nearly half of them are children under the age of 15.

Syrian refugees’ potentially protracted residence primarily in host communities is an important factor to consider in the services and opportunities that they are able to access, including work permits, cash assistance, food vouchers, public schools and public healthcare.

Registration determines refugees’ access to most services in Jordan: while documentation requirements compound the difficulties they face, recent reforms have improved access.

Since the Syrian conflict started in 2011, Jordan has experienced an influx of refugees seeking safety. Almost 1.3 million Syrians were living in Jordan as of the 2015 Population Census (Department of Statistics, Jordan, 2015). It is important to understand the characteristics of this community in order to protect their rights and provide them with services such as education, healthcare and work.

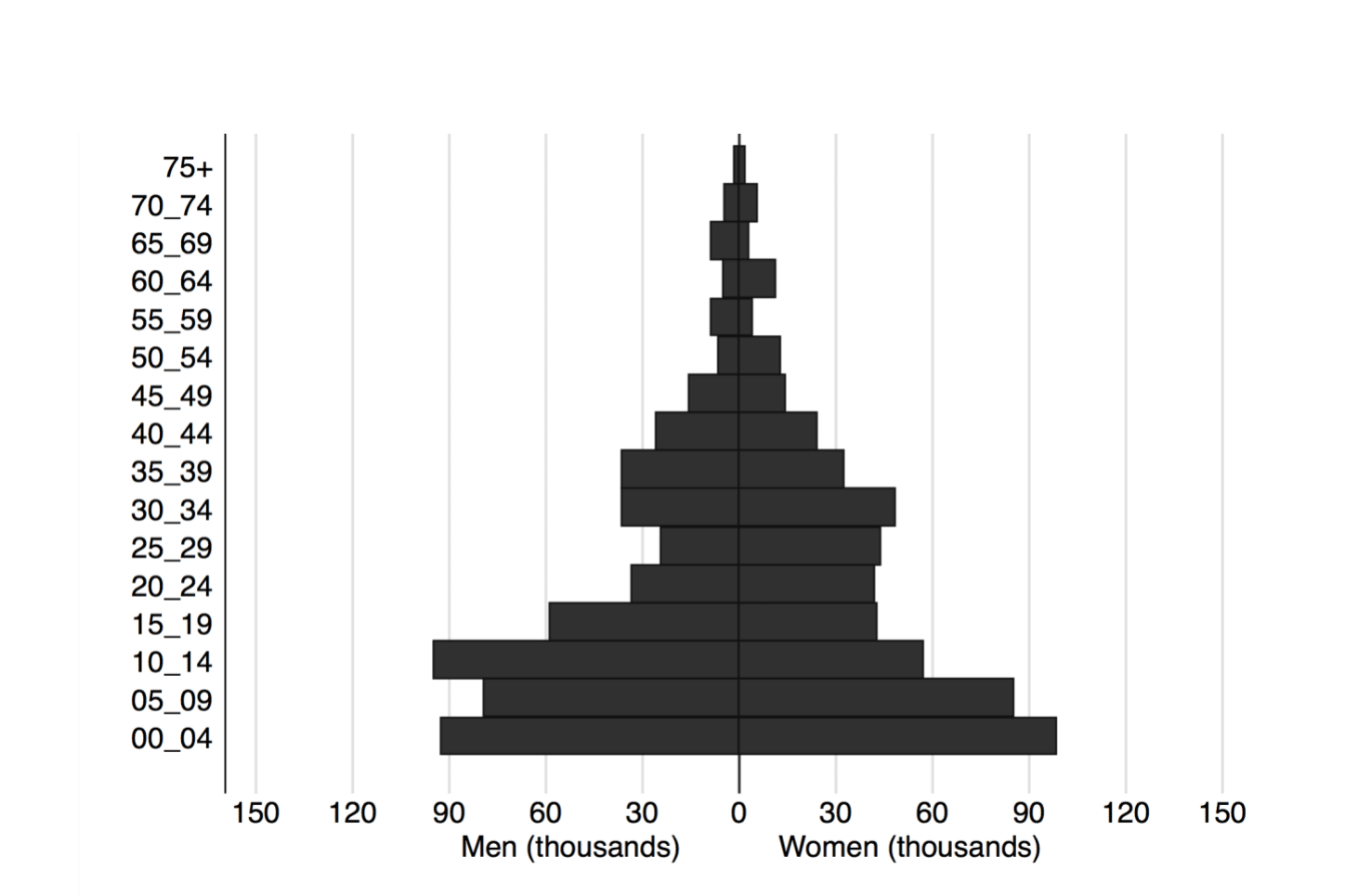

Syrian refugees are primarily children

The Syrian refugee population in Jordan is very young. Figure 1 shows the population structure of Syrian refugees in Jordan based on the new Jordan Labor Market Panel Survey 2016. Children under the age of 15 make up nearly half (48%) of the Syrian refugee population.

There are fewer men than women in the 20-34 age groups. Men aged 20-34 may have remained in Syria to fight; they may have died due to the conflict; or they may have chosen to seek asylum in a different country. As a result, in 2016, a woman led 23% of Syrian refugee households compared with 14% of Jordanian households (Krafft et al, 2018).

The high shares of children and female-headed households are important factors shaping Syrians’ need for services and potential contributions to Jordan’s economy.

Figure 1. Population structure of Syrian refugees in Jordan (in thousands), by age group and sex, 2016

Source: Krafft et al. (2018)

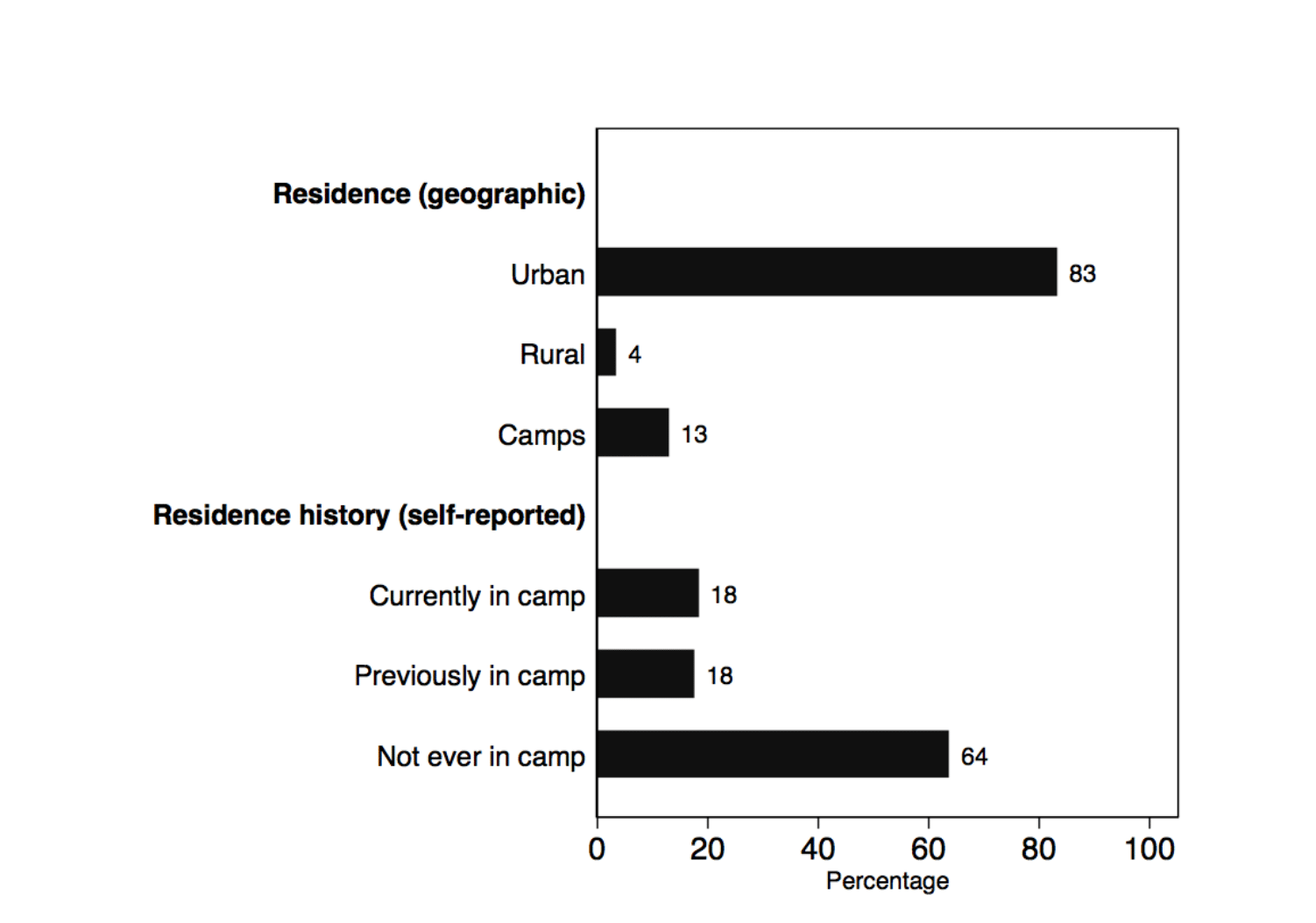

Most Syrians live in host communities

The majority of Syrian refugees live in host communities (87%). Figure 2 shows Syrian refugees’ official geographical residence, as well as their self-reported current (as of 2016) residence and residence history. About 83% of Syrian refugees live in host communities in urban areas; few Syrian refugees (4%) are rural residents; while 13% are in refugee camps.

When asked to self-report their current residence, more Syrian refugees (18%) reported currently living in a camp, which may represent individuals living in unofficial camps or informal tented settlements (REACH, 2014). A sizeable share of refugees (18%) also reported living in camps previously.

Syrian refugees have been in Jordan for multiple years and face a protracted stay, making access to services all the more critical for the development of this young population. Most Syrian refugees in Jordan arrived in 2013 or earlier; only 13% arrived in 2014 or later.

Refugees’ options for return to Syria long-term may also be limited, as 64% left Syria when the government was controlling their home town, compared with 36% leaving when the opposition was in control (Krafft et al, 2018). Syrians’ long-term and potentially protracted residence primarily in host communities is an important factor to consider in the services and opportunities they may be able to access.

Figure 2:

Current residence and residence history of Syrian refugees aged 15-59 in Jordan (percentage), 2016

Source: Krafft et al (2018)

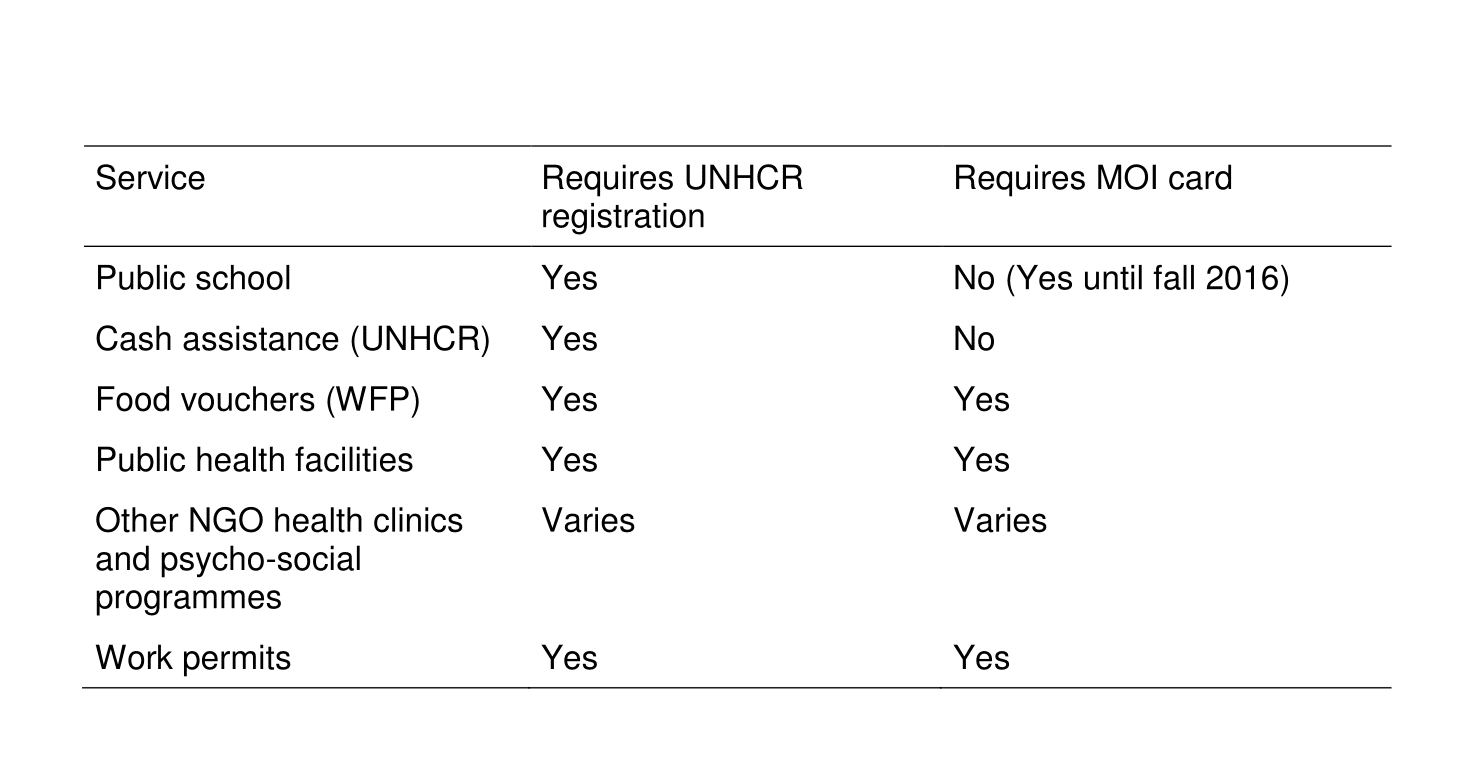

Refugees must be registered to access most services

Refugee registration determines access to most services in Jordan. Refugees must register with both the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Jordanian Ministry of Interior (MOI). As of March 2018, there were 659,063 Syrians registered as refugees with UNHCR (UNHCR, 2018).

In addition, to register with the MOI and obtain a service card, Syrians must go to their local police station with identity documents, confirmation of their place of residence, and a health certificate. If Syrians move districts they must re-apply for a new MOI service card. Syrians who left camps without permission have historically been unable to receive new documentation (Salemi et al, 2018).

Not all 1.3 million Syrians who fled to Jordan are registered with UNHCR and the MOI. This limits their access to important services, as shown in Table 1.

Refugees who are registered have access to services such as work permits, cash assistance, food vouchers, public schools and public healthcare. Refugees who are not registered may have to live in poverty with fewer services and resources. Even refugees who are registered may still face barriers in accessing services, for example, difficulties in paying for healthcare even at public facilities (Doocy et al, 2016).

Table 1:

Access to services by documentation requirements

Improving Syrians’ access to services by overcoming documentation challenges

Syrians in Jordan are a predominantly young population in need of substantial support. Refugees need services regardless of whether they are registered with UNCHR or have a MOI card. Documentation should not be a barrier to accessing services, particularly for children.

Two recent policy changes in Jordan show important promise for improving access to needed services despite documentation challenges.

The first reform was that Syrian refugee children’s access to school no longer depends on having a service card. Initially, documentation requirements were waived for fall 2016 (Jordan Times, 2016). The temporary waiver became official policy in 2017 (Abed, 2017).

This policy shift has been widely praised for its positive impact on the futures of Syrian children in Jordan. Documentation barriers to other services should be reconsidered as well.

The second reform was in March 2018, when the MOI and UNHCR launched a joint campaign to formalise and document Syrians living without registration in urban areas of Jordan (Jordan Times, 2018). The campaign will run until September 2018, targeting refugees who left the camps without authorisation as well as refugees who never registered.

This campaign provides an important opportunity for Syrians to gain legal status in Jordan, free of charge. Receiving documentation will allow refugees greater access to services and benefits.

The Jordanian government and UNHCR should continue these efforts to make documentation accessible for Syrian refugees as well as lowering documentation requirements for needed services. Helping Syrian refugees gain access to services will help them to rebuild their country in the future. In the meantime, these Syrian refugees will also be better able to contribute to Jordan’s economy and society.

Further reading

Abed, Mahmoud Al (2017) ‘Jordan Allows Syrian Children with No Documents to Join Schools – Officials’, Jordan Times, 24 September.

Department of Statistics, Jordan (2015) ‘Table 8.1: Distribution of Non-Jordanian Population Living in Jordan by Sex, Nationality, Urban/ Rural and Governorate.’ Population and Housing Census 2015.

Doocy, Shannon, Emily Lyles, Laila Akhu-Zaheya, Ann Burton and Gilbert Burnham (2016) ‘Health Service Access and Utilization among Syrian Refugees in Jordan’, International Journal for Equity in Health 15(108): 1-15.

Jordan Times (2016) ‘HRW Commends Positive Steps on Education for Syrian Children’, 23 August.

Jordan Times (2018) ‘Ministry, UNHCR Launch Campaign to Regularise Status of Syrian Refugees in Urban Areas’, 4 March.

Krafft, Caroline, Maia Sieverding, Colette Salemi and Caitlyn Keo (2018) ‘Syrian Refugees in Jordan: Demographics, Livelihoods, Education, and Health’, ERF Working Paper No. 1184.

REACH (2014) ‘Syrian Refugees Staying in Informal Tented Settlements in Jordan: Multi-Sector Assessment Report’, REACH.

Salemi, Colette, Jay Bowman and Jennifer Compton (2018) ‘Services for Syrian Refugee Children and Youth in Jordan: Forced Displacement, Foreign Aid, and Vulnerability’, ERF Working Paper, forthcoming.

UNHCR (2018) ‘Situation Syria Regional Refugee Response’.