In a nutshell

Analysis of monetary policy in Egypt indicates that a fixed exchange rate regime generates the highest output and inflation variability, in addition to the worst loss function for the economy.

As the exchange rate is allowed more flexibility, the variability of output and inflation declines.

Monetary policy has many more opportunities to correct its mistakes when targeting inflation rather than the exchange rate.

Inflation targeting is one of the operational frameworks for monetary policy aimed at attaining price stability. In contrast to alternative strategies, notably money or exchange rate targeting, which seek to achieve low and stable inflation through targeting intermediate variables – for example, the growth rate of money aggregates or the level of the exchange rate against an ‘anchor’ currency – inflation targeting focuses directly on inflation.

Economic research has identified a relatively long list of requirements for countries trying to operate a successful inflation targeting framework. Key among them is the need for increased exchange rate flexibility to eliminate confusion surrounding the central bank’s nominal anchor.

But in many cases, particularly in emerging markets, inflation targeting is pursued without completely fulfilling the exchange rate requirements. This is done on the grounds that there is a high pass-through from exchange rate fluctuations to inflation in these countries. Hence, it is argued, if the overriding concern is to reduce inflation variability and, in turn, output variability, there will be a tendency to maintain some exchange rate rule.

Although a functioning exchange rate transmission channel may add to the effectiveness of monetary policy under inflation targeting, actively manipulating the exchange rate along with inflation is likely to worsen the performance of monetary policy. But this does not imply that central banks should not pay attention to the exchange rate.

While inflation targeting may be a framework that is typically free from formal exchange rate commitments, it is nonetheless not free from exchange rate considerations. The apparent reluctance of policy-makers to take a completely hands-off approach to the exchange rate may reflect neither an irrational fear nor an unconditional distaste for floating per se.

There are many good reasons for any open economy to be concerned about certain types or magnitudes of exchange rate movements, such as the high degree of exchange rate pass-through, effects on the external sector, financial stability and market functioning.

Against this background, research and country experience in this area have focused on introducing an exchange rate term into the central bank’s reaction function under an inflation targeting regime.

My work builds on this research by presenting a small open economy structural gap model with forward-looking expectations and with an endogenous monetary policy response for the case of Egypt (Al-Mashat, 2011). The study examines the consequences of various approaches to the conduct of monetary policy by presenting the variability of inflation and output in the light of alternative degrees of exchange rate intervention under an inflation targeting regime for Egypt.

As is evident in Figures 1 and 2, the closer the system is to a fixed exchange rate regime, the higher are the inflation variability and output variability. The variability starts to decline as the exchange rate starts to become more flexible. Unsurprisingly, this is consistent with a situation where the central bank adopts a monetary policy reaction function that is closer to an inflation targeting regime.

In pegged regimes, central banks are punished for their mistakes by financial markets, which act swiftly and with a force that is hard to counteract. On the other hand, mistakes in inflation targeting regimes are punished by consumers (and the public in general) through their expectations – and these evolve only gradually. In practice, then, monetary policy has many more opportunities to correct its mistakes when targeting inflation rather than the exchange rate.

The higher volatility of the variables under a fixed exchange rate regime does not come from the absence of the direct exchange rate to inflation channel of transmission. It is the demand side that stabilises the economy.

In driving demand, however, the real exchange rate does not help to stabilise the shock when the nominal exchange rate is fixed as much as when the exchange rate is flexible. Hence, nominal (and real) interest rates have to move more to compensate for this.

In other words, the conduct of monetary policy targeting inflation while maintaining a fixed exchange rate regime has to count on a larger volatility of its main macroeconomic variables, particularly output.

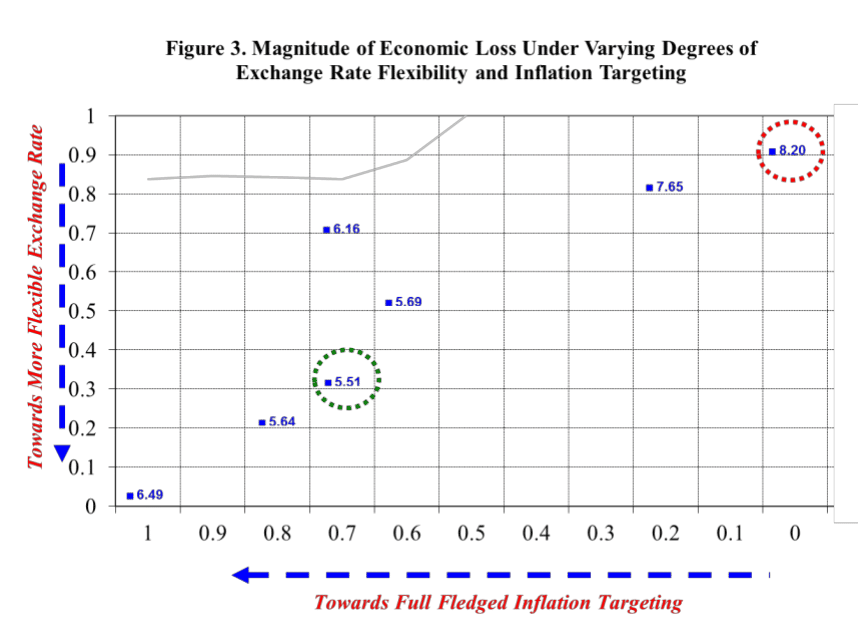

In addition to examining inflation and output variability, it is important to evaluate the ‘loss function’ under the various exchange rate flexibility and inflation targeting scenarios. The loss function summarises the trade-off between inflation and output by providing a combination of inflation and output variability rather than emphasising the importance of one variable over the other.

Previous results are confirmed in Figure 3, where the fixed exchange rate regime provides the highest loss in terms of inflation and output variability put together.

To sum up, the results reveal that a fixed exchange rate regime generates the highest output and inflation variability, in addition to the worst loss function for the economy. As the exchange rate is allowed more flexibility, the variability of output and inflation declines.

Further reading

Al-Mashat, Rania (2011) ‘Assessing Inflation and Output Variability using a New Keynesian Model: An Application to Egypt’, in Money in the Middle East and North Africa: Monetary Policy Frameworks and Strategies edited by David Cobham and Ghassan Dibeh, Routledge.

Al-Mashat, Rania (2007) ‘Monetary Policy in Egypt: A Retrospective and Preparedness for Inflation Targeting’, Egyptian Center for Economic Studies Working Paper No. 134.

Al-Mashat, Rania, and Andreas Billmeier (2008) ‘The Monetary Transmission Mechanism in Egypt’, Review of Middle East Economics and Finance 4(3).

Benes, Jaromir, and David Varva (2004) ‘Exchange Rate Pegs and Inflation Targeting: Modeling the Exchange Rate in Reduced Form New Keynesian models’, mimeo, Czech National Bank.

Berg, Andrew, Philippe Karam and Douglas Laxton (2006) ‘Practical Model-based Monetary Policy Analysis – A How-to Guide’, International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 06/81.