In a nutshell

Citizens’ trust in the government in Lebanon is unambiguously lower in 2024 compared with 2013 and 2016; the pattern is similar for parliament, with trust having been in significant decline since 2016.

While public confidence in the governance of civil institutions continues to erode, the army remains a resilient and trusted institution; this is an unprecedented divide in institutional trust.

Amid this bleak outlook for civil institutions, there is a glimmer of hope: the emergence of new political voices in parliament offers potential for subtle shifts in the dynamic.

The election of General Joseph Aoun as president of Lebanon in early 2025, followed by Nawaf Salam’s selection as prime minister, comes at a critical juncture after years of institutional paralysis.

In previous research (Fakih et al, 2022), we documented a significant erosion of trust in Lebanese public institutions between 2013 and 2016, followed by controversial fiscal policies that inflated public sector salaries through a central bank Ponzi scheme. In Makdissi et al (2025), we document how these measures temporarily reduced poverty levels, only to trigger unprecedented hardship across the country following their collapse in the autumn of 2019.

As Lebanon’s new leadership confronts these daunting economic challenges amid regional tensions, understanding the evolution of citizens’ trust in public institutions becomes crucial.

In new research, we examine the evolution of trust in three key institutions – parliament, the government and the armed forces – using four waves of Arab Barometer surveys: July 2013, July-August 2016 (during a presidential vacuum), September-October 2019 (just before the 17 October uprising) and February 2024 (during another presidential vacuum and southern border tensions following the 7 October 2023 events in Gaza).

Each survey measured institutional trust on a four-point Likert scale: No trust at all, Not a lot of trust, Quite a lot of trust and A great deal of trust.

To analyse these ordinal trust measures, we first follow the standard practice of dichotomising responses, defining institutional trust as the proportion of respondents expressing either Quite a lot of trust or A great deal of trust.

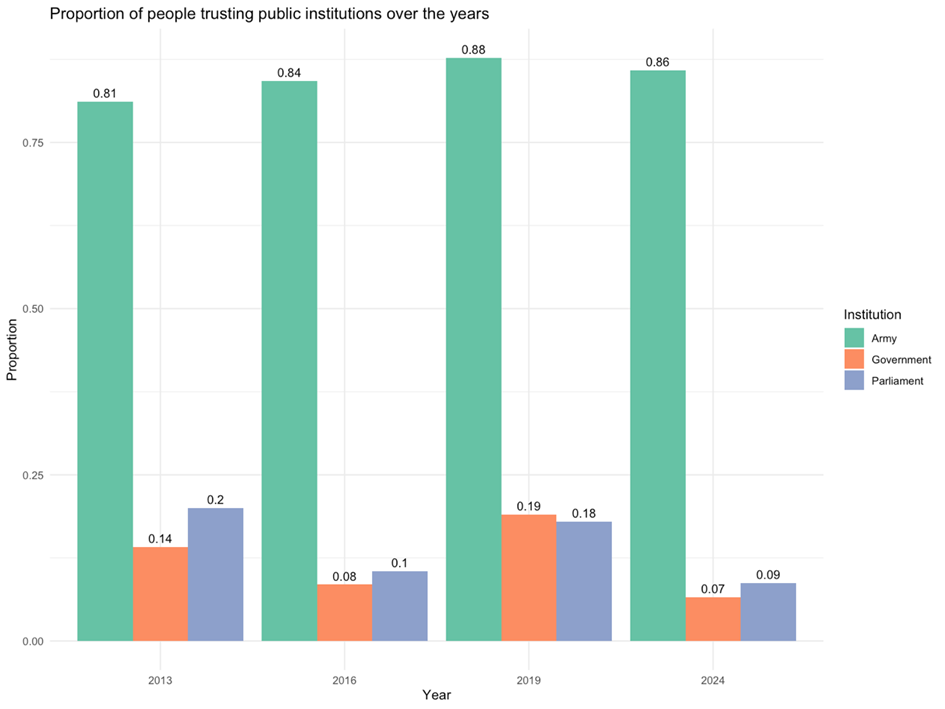

Figure 1 reveals a striking divergence between military and civilian institutions. While trust in the Lebanese armed forces remained consistently high and gradually strengthened to exceed 85% by 2024, confidence in both the government and parliament followed a marked downward trajectory. The sole exception was a brief uptick in trust in civilian institutions in 2019, coinciding with the period of artificial economic prosperity before the collapse of the central bank’s Ponzi scheme by the autumn of 2019 (Makdissi et al, 2025).

By 2024, these civilian institutions retained the confidence of less than 10% of the population, creating an unprecedented divide in institutional trust.

Figure 1: Proportion of people trusting public institutions

While dichotomising trust responses provides clear initial insights, it overlooks important nuances in the ordinal data. A natural statistical approach to summarise the complete distribution of a variable is to compute its mean. Unfortunately, using summary statistics such as means with ordinal variables can be misleading, as results may not be robust to changes in the numerical scale applied to the ordinal categories.

Allison and Foster (2004) demonstrate that robust comparisons of ordinal variables are possible through first-order stochastic dominance: if the cumulative distribution of trust in distribution A first-order stochastically dominates that of distribution B, then any increasing numerical scale applied to the trust categories will result in distribution A having a higher average trust level than distribution B.

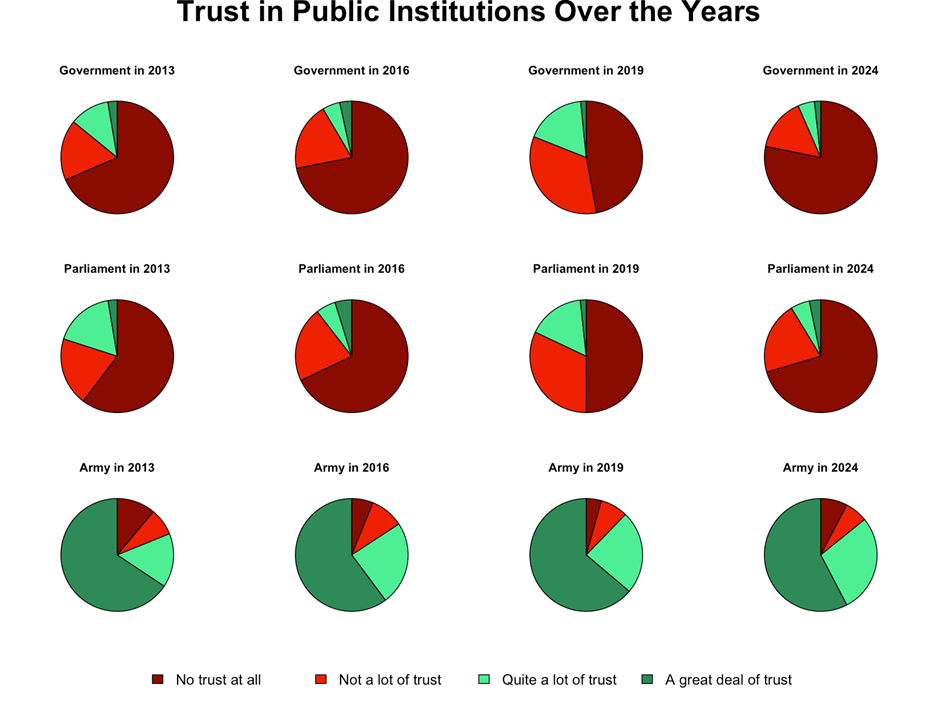

To make this technical concept accessible to a general audience, we use pie charts as a visual tool for representing first-order dominance. Starting from No trust at all, we can establish that trust has unambiguously declined if:

- The segment for No trust at all has grown.

- The combined segment for No trust at all and Not a lot of trust has expanded.

- The segment combining the first three categories (No trust at all, Not a lot of trust and Quite a lot of trust) has increased.

This data visualisation approach allows us to identify robust changes in trust levels across institutions and time periods, complementing our previous analysis while avoiding the potential pitfalls of using summary statistics for ordinal data analysis.

Figure 2: Trust in public institutions

Figure 2 presents pie charts for trust in parliament, the government and the armed forces across all four survey waves. The visual contrast is striking: while the army’s pie charts are dominated by shades of green representing the high trust categories, those for civil institutions (that is, the government and parliament) are overwhelmingly coloured red, representing low trust categories.

Beyond these visual patterns, our analysis reveals several robust findings about the evolution of institutional trust in Lebanon.

The temporal analysis shows a clear deterioration in the level of trust in civil institutions compared with the relatively stable level of trust in military institutions and a marked increase in these trust levels between 2016 and 2019. As for trust in the government, it is unambiguously lower in 2024 compared with 2013 and 2016. A similar pattern is depicted for parliament, similarly with a significant decline since 2016.

Turning to cross-institutional comparisons, we note the army’s consistent dominance in public trust. In every survey wave from 2013 to 2024, the armed forces have unambiguously higher trust than civil institutions.

But 2024 presents a new pattern within civil institutions: trust in parliament exceeds trust in the government. This change might reflect the impact of the 2022 parliamentary elections, which saw the unprecedented entry of opposition parliamentarians from civil society movements into the legislature, offering a small but a significant alternative to traditional political forces.

These findings highlight not only the persistence but also the deepening of Lebanon’s divide in institutional trust. While the army remains a resilient and trusted institution, public confidence in the governance of civil institutions continues to erode. But amid this bleak outlook for civil institutions, there is a glimmer of hope: the emergence of new political voices in parliament offers potential for subtle shifts in this dynamic.

Further reading

Allison, RA, and JE Foster (2004) ‘Measuring health inequality using qualitative data’, Journal of Health Economics 23: 505524.

Fakih, A, P Makdissi, W Marrouch, R Tabri and M Yazbeck (2022a) ‘A stochastic dominance test under survey nonresponse with an application to comparing trust levels in Lebanese public institutions’, Journal of Econometrics 228: 342-58. Makdissi, P, W Marrouch and M Yazbeck (2025) ‘Monitoring poverty in a data-deprived environment: The case of Lebanon’, Review of Income and Wealth 71(1): e12708.