In a nutshell

In most countries of the Arab world, the proportion of the population trusting the government has diminished over the years between 2013 and 2022; the only exception is Libya, which has moved in the opposite direction.

The decline in trust across many countries, particularly Iraq and Lebanon, is a stark reminder of the challenges that governments face in maintaining legitimacy amid economic hardship, corruption and external influence.

Strengthening governance, ensuring accountability and promoting inclusive economic development should be priorities to reverse growing distrust, which could otherwise be a precursor to further instability.

More than a decade ago, the Arab Spring sparked a wave of protests across several countries in the Middle East and North Africa, driven by their populations’ lack of trust in their governments. After a decade, examining how this trust has evolved in the years following these uprisings is crucial.

In this column, I leverage data from Waves III and VII of the Arab Barometer to explore the changes in trust in Arab governments over the past decade. The Arab Barometer provides information on public trust by asking respondents how much they trust their government. This analysis focuses on eight countries where data were collected in both waves: Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Sudan and Tunisia.

The experience of the Arab Spring was not the same among the countries for which we have data. In Iraq, protests focused on government corruption and inadequate services, while Jordan saw peaceful demonstrations that led to political reforms under King Abdullah II. Lebanon initially experienced limited calls for reform, but growing dissatisfaction culminated in the mass protests in the autumn of 2019, driven by economic collapse and corruption.

In Morocco, protests prompted constitutional changes that increased parliamentary powers. Palestine saw limited direct impact from the Arab Spring, as the focus remained on Israeli occupation, though small protests were calling for improved governance. Sudan saw more profound change later, with protests leading to the ousting of President Omar al-Bashir in 2019. Tunisia, where the Arab Spring began, made a successful transition to democracy after ousting President Ben Ali, though it is now moving away from democracy under President Kais Saied.

Measuring trust

For ease of reference, I refer to the results from Wave III, collected between 2012 and 2014, as ‘2013’, and the results from Wave VII, conducted in 2021 and 2022, as ‘2022’. This comparison offers a valuable perspective on how public trust in Arab governments has shifted since the Arab Spring.

The trust question in the Arab Barometer has four ordinal categories: No trust at all, Not a lot of trust, Quite a lot of trust, and A great deal of trust. I first estimate the proportion of the population trusting their government. I define this category as incorporating those answering Quite a lot of trust or A great deal of trust to the question.

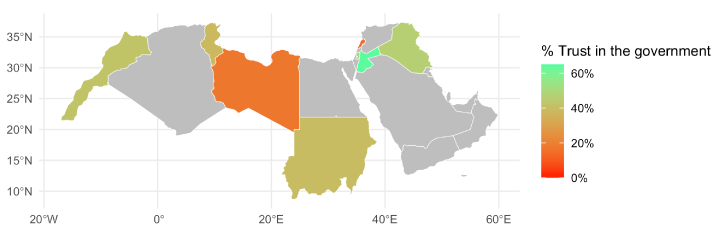

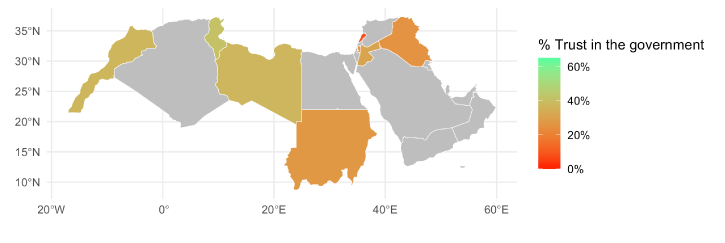

Figures 1 and 2 present these estimates for 2013 and 2022, respectively. Each country’s colour on these maps signifies the percentage of people trusting the government, ranging from vibrant green (65%) to stark red (0%).

A striking pattern quickly becomes evident: in most countries, the proportion of the population trusting the government has diminished over the years, with the colours shifting noticeably from green to red, except for Libya, which moves in the opposite direction.

Splitting the sample in two categories based on the answer to an ordinal variable, as I did to produce Figures 1 and 2, overlooks part of the information that is incorporated in the variable. For this reason, it is often desirable to look at other summary statistics. Unfortunately, as I explained in two previous columns on happiness and freedom (Makdissi, 2024a and 2024b), using a summary statistic, such as the mean, with an ordinal variable may lead to results that are not robust to a change in the increasing numerical scale applied to this ordinal variable.

In this context, Allison and Foster (2004) show that if the cumulative distribution of this ordinal variable in population A first order dominates the cumulative distribution in population B, then the mean of this ordinal variable in distribution A is higher than in distribution B for any increasing numerical scale one applies to this ordinal variable.

In any dataset, some variables have missing values for some observations. Often, the analyst assumes these missing values are random and uses the rest of the survey as a representative subsample. Making this assumption about sensitive questions such as ‘Tell me how much you trust the government’ may be problematic, as the refusal to answer a question is most probably related to the level of trust a person has in institutions.

Using a known result from Horowitz and Manski (1995), Fakih et al (2022a) propose a modified version of the Allison and Foster (2004) condition to study the evolution of trust in public institutions in Lebanon between 2013 and 2018 to account for non-randomness in non-answering the question.

For the distribution of population A to first-order dominate the distribution of population B for any assumption one could make on missing values-generating process, the upper bound of the set of all potential cumulative distributions of population A has to be below the lower bound of the set of all potential cumulative distributions of population B. To create the upper bound for population A, one must allocate all no-answers to No trust. To create the lower bound for population B, these non-answers must be allocated to A great deal of trust.

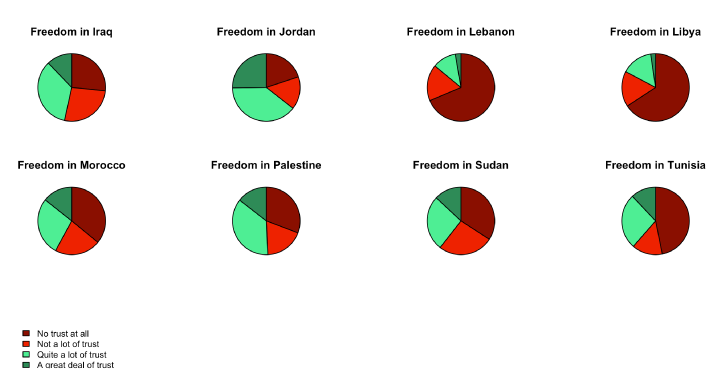

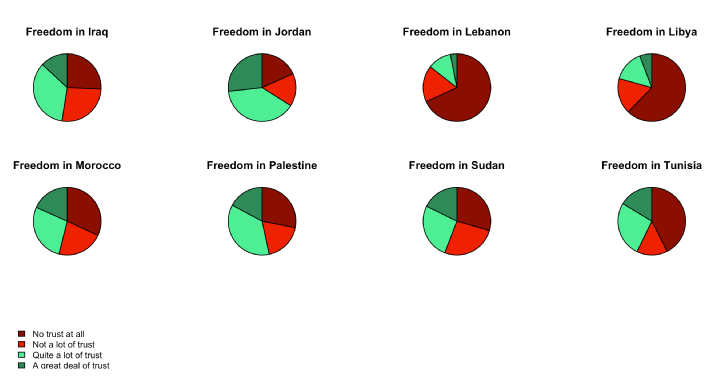

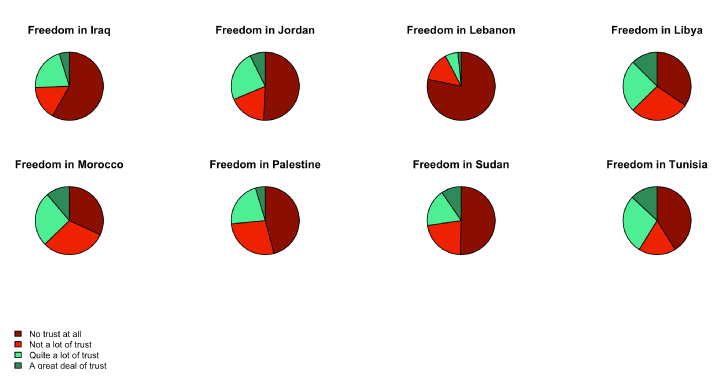

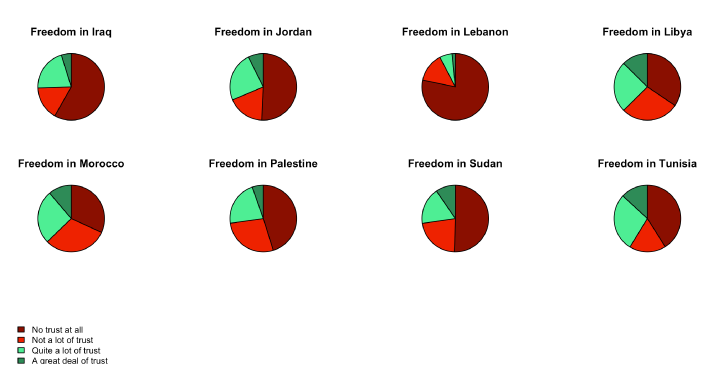

In the rest of this column, I use the condition in Fakih et al (2022a) to identify robust comparisons of trust in the government in the Arab countries for which we have data. The first-order stochastic dominance condition can be identified visually using pie charts. For population A to have a higher average trust than population B for any increasing numerical scale:

- The pie chart segment representing the No trust at all category should be smaller in the upper-bound pie chart of population A than in the lower-bound pie chart of population B.

- When combining the No trust at all and Not a lot of trust segments, this combined segment should be smaller in the upper-bound pie chart of population A than in the lower-bound pie chart of population B.

- Adding the Quite a lot of trust segment to the previous categories, the combined segment should still be smaller the upper-bound pie chart of population A than in the lower-bound pie chart of population B.

The important result here is that this condition, laid down in Fakih et al(2022), is based on the minimum number of assumptions: the only assumption is the requirement for the numerical scale is that it is non-decreasing (a weaker version of increasing). No assumption is made on the missing values-generating process. In this context, the condition gives results that are valid for any increasing numerical scale one could use to compute the average of the ordinal trust variable and to any assumption and model an analyst could impose on the missing values-generating process. In this sense, many would consider this condition to be too strong.

Trust in governments in Arab countries

Figures 3 and 4 present the upper and lower bounds pie charts of the trust distributions for 2013, while Figures 5 and 6 highlight the corresponding pie charts for 2022. A surprising result is that, although the condition in Fakih et al (2022a) may be considered too strong, many rankings of change in the level of trust in governments within Arab countries over the decade are robust.

Key findings reveal a robust decline in average trust in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and Sudan, regardless of the numerical scale used to interpret the ordinal trust categories and the assumption on the missing values-generating process. In contrast, Libya demonstrates a robust increase in average trust levels, aligning with the earlier findings from Figures 1 and 2.

The direction of change in trust levels in Morocco and Tunisia is not robust. For these countries, trust is sensitive to the choice of numerical scales and the missing values-generating process, with some combinations of assumptions indicating an increase in trust while others show a decrease.

The growing distrust across many Arab countries is a worrisome trend, raising concerns about future political and social instability. Policy-makers must consider this an early warning signal and address the underlying causes.

In 2013, Jordan stood out as a clear leader in terms of trust in government. Jordan’s population exhibited higher trust in its government than the other seven countries studied. On the other hand, Lebanon and Libya were ranked lowest, with lower trust in their respective governments than in the other six countries.

By 2022, the situation had shifted dramatically. Lebanon remains at the bottom of the rankings, with the lowest average trust in government. This reflects the economic collapse, continuing political instability and the devastating Beirut Port explosion of 2020. The banking crisis of 2019, dubbed a nationwide Ponzi scheme, and the government’s failure to address the economic collapse further exacerbated public distrust, as highlighted by Fakih et al (2022b).

Iraq, which previously held a mid-level position in 2013, has now fallen to second from the bottom, just above Lebanon. Iraq’s decline may be partially attributed to the violent suppression of protests in 2019, an event with striking parallels to the Lebanese demonstrations of the same year.

Conversely, Libya, which had ranked among the lowest in 2013, has now risen to join Morocco and Tunisia at the top of the trust rankings in 2022. Libya’s relative improvement is likely to be linked to hopes for peace and stability following the formation of the Government of National Unity in 2021, after years of conflict. The increased stability offers optimism, but it will be necessary to monitor whether this upward trend in trust is sustained.

Meanwhile, Jordan’s position has declined sharply. From leading the trust rankings in 2013, Jordan now ranks just above Iraq and Lebanon. This significant drop is potentially driven by budgetary decisions that have exacerbated poverty (35%) and unemployment (21.4%), as discussed by Ersan (2024).

Conclusions

The findings reveal a dynamic and often fragile landscape of trust in Arab governments between 2013 and 2022. Libya’s rise and Jordan’s fall exemplify how shifting political, economic and social conditions directly affect public trust in leadership. The decline in trust across many countries, particularly Iraq and Lebanon, is a stark reminder of the challenges that governments face in maintaining legitimacy amid economic hardship, corruption and external influence.

For policy-makers, these results underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions that restore faith in institutions. Strengthening governance, ensuring accountability and promoting inclusive economic development should be priorities to reverse growing distrust, which could otherwise be a precursor to further instability. Ensuring these efforts are grounded in the real concerns of populations will be essential to rebuilding trust and avoiding social unrest in the future.

Further reading

Allison, RA, and JE Foster (2004) ‘Measuring health inequality using qualitative data’, Journal of Health Economics 23: 505-24.

Ersan, M (2024) ‘Jordan: How to Read the Election Results and Why the Islamists Came Out Ahead’, Arab Reform Initiative, Bawader/Commentary.

Fakih, A, P Makdissi, W Marrouch, R Tabri and M Yazbeck (2022a) ‘A stochastic dominance test under survey non-response with an application to comparing trust levels in Lebanese public institutions’, Journal of Econometrics 228: 342-58.

Fakih, A, P Makdissi, W Marrouch, R Tabri, and M Yazbeck (2022b) ‘Élections au Liban: est-ce la fin pour les dirigeants kleptocrates qui ont mis le pays en faillite?’, La Conversation.

Horowitz JL, and CF Manski (1995) ‘Identification and robustness with contaminated and corrupted data’, Econometrica 63: 281-302.

Makdissi, P (2024a) ‘Happiness in the Arab world: should we be concerned?’, The Forum: ERF Policy Portal.

Makdissi, P (2024b) ‘Freedom: the missing piece in multidimensional well-being analysis’, The Forum: ERF Policy Portal.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.