In a nutshell

The GPA can act as an anchor for economic reforms, whether they are of investment policy, procurement procedures, export strategy or the institutional and legal framework – this is important for Arab countries.

But joining the GPA in itself might not help if the surrounding business and investment environment is not ready, and the human capacity concerned with implementation remains reluctant to do so.

Joining the GPA with its flexible provisions should be prudently applied by the implementing agencies in Arab countries to ensure that they serve development purposes and are not hijacked by special interests.

Public procurement in Arab countries is governed by laws on tendering and related regulations and decrees, which are typically complicated. The central problem is the widening gap between what is stated in the laws and what happens in reality. In Egypt and the Gulf countries, for example, the contracting ministries and agencies have created their own unwritten procurement rules, which have become known to bidders over time (Modaffari, 2023; Shreiber et al, 2020).

Hence, despite the fact that the governing laws in general have been assessed to allow for fair competition and non-discrimination (EBRD, 2012, 2013), the lack of specific regulations and the discretionary power granted for contracting agencies have pre-empted the laws and created room for corruption.

Efforts to reform the procedures associated with public procurement in a number of Arab countries have remained modest. This is mainly a result of the vested interests involved in the process and the lack of efficient institutional set-ups that govern the process (Modaffari, 2023; Shreiber et al, 2020).

Existing international databases, such as the Global Public Procurement Database published by the World Bank, do not include data on Arab countries, with the exception of some information on Saudi Arabia. The estimated value of public procurement in Arab countries varies significantly from a low of 5% of GDP in countries like Sudan and Yemen to around 20% in countries like Egypt (ITC, 2023). These shares compare with a world average that is in the range 12-14% (Bosio and Djankov, 2020).

In light of such facts, it remains an open question whether joining Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA) of the World Trade Organization (WTO) can help Arab countries to improve their public procurement systems in terms of efficiency and enhancement of transparency while overcoming the expected negative effects on development.

What could the GPA do for Arab countries?

In general, the revised version of the GPA introduced in 2014 was intended to make accession easier, and it includes several elements of flexibility intended to cater for the sensitivities of developing countries. Aspects such as price preferences, offsets, phased-in additions of specific entities and sectors, as well as thresholds that are initially set higher than their permanent levels, have eased the process of accession for developing countries (Anderson and Müller, 2020; Yukins and Schnitzer, 2015).

There are currently 49 members of the GPA, and 35 observers including four Arab countries – Bahrain, Jordan, Oman and Saudi Arabia – with Jordan and Oman in the process of negotiating accession (WTO, 2024). Despite the fact that developing countries have tended to be reluctant to apply for GPA accession, all countries that have applied recently are developing economies.

So is it a good or bad idea for Arab countries to join the GPA? To answer this question, we identify three key pillars associated with socio-economic development (following Anderson et al, 2011; and Chakravarthy and Dawar, 2011) and ask whether GPA accession can help Arab countries to achieve them.

Enhancing exports and inward foreign direct investment

First, Arab countries’ major trading partners besides China are the European Union (EU) and the United States, which are already members of the GPA. The total market value of government procurement in the world was estimated at $11 trillion in 2018 (Bosio and Djankov, 2020). This had increased to $13 trillion in 2021 (ITC, 2021), although what really counts is the market penetration rate.

Moreover, Arab countries are widening their web of free trade areas with members of the GPA. There is no guarantee that such information on trade will be easily translated into equivalent information on public procurement. Yet, empirical evidence has confirmed that GPA membership has a positive impact on trade in goods and services between GPA parties as well as on outward service sales by foreign affiliates (Anderson, et al, 2014; Chen and Whalley, 2011).

The second issue that needs to be considered is the presence of China among the countries seeking GPA accession. This will be worrying for all GPA members, not just Arab countries, due to China’s aggressive use of price competition. China’s accession will probably be subject to strict conditions that ensure that such aggressive behaviour will be handled in its terms of accession. Hence, we cannot depend on this factor as one of the criteria to evaluate Arab countries’ accession to the GPA.

The GPA can also act as an engine for enhancing inbound foreign direct investment (FDI). This is especially true in fields that require domestic establishment, for example, construction activities, which represents a significant portion of government procurement in Gulf countries as well other Arab countries such as Egypt and Libya. Since there are no published data on the size of public procurement in Arab countries, GPA membership can act as ‘stamp of approval’ for the investment and procurement policy of the country concerned, which would help to encourage more FDI (Anderson, et al, 2011).

Promoting good governance, enhancing competition and reducing costs

Joining the GPA will surely help to enhance competition and reduce costs (Anderson et al, 2011) as it will act as an effective device for enhancing transparency and abiding by rules. Fears that efficiency gains enjoyed by the government from joining the GPA will not be shared by local suppliers, who might be kicked out of the market due to fierce foreign competition, are contained due to the flexibility embedded in the accession process.

Identifying phased-in additions of specific sectors and entities (including defence departments), offsets (including local content requirements), price preferences and thresholds will enable the government to take account of sensitive sectors and/or small firms. As a matter of relief for Arab countries, estimates of government procurement that falls outside the GPA’s purview for a developed member have been 80% of total public EU procurement (Anderson, et al, 2011) a share that is expected to be higher for developing countries.

This is not to mention the ‘home bias’ in the procurement systems of Arab countries, which is typically driven by many factors, including compliance costs and the domestic policy environment. These act as a shield from high substitution of foreign firms for domestic ones in procurement activities.

Moreover, the negative impact on the economy would be reduced by the high probability of foreign firms that win the bids subcontracting local firms – and the subsequent possibility of technology transfer. Moreover, empirical evidence shows that joining the GPA has not led to an increase in the value of foreign procurement in the countries that have joined, although it has increased the import demand for contracts (Shingal, 2011).

Another fear that can act as an obstacle is the negotiating costs as well as the costs of altering different laws, rules and regulations related to adapting domestic law and regulations to the GPA. Such costs, which are relatively significant, can be reduced through the technical and financial support provided by international organisations and donors.

Moreover, the majority of Arab countries are not federal states, and hence government procurement is governed by a central law, which will reduce the costs associated with adapting to the GPA compared with federal systems. Finally, the flexibilities embedded in the accession process are certainly an important aspect that should be considered if Arab countries decide to join.

Fighting corruption, anchoring reforms and enhancing transparency

The GPA in itself can act as an anchor for reforms, whether that is of investment policy, procurement procedures, export strategy or the institutional and legal framework. This is important for Arab countries.

Corruption is a worldwide phenomenon in public procurement, especially in developing countries (Shingal, 2015). As a result, joining an international agreement like the GPA can act as an effective device in initiating and anchoring reforms on several fronts whether related directly to procurement policy or to related issues, including corruption, investment and exports.

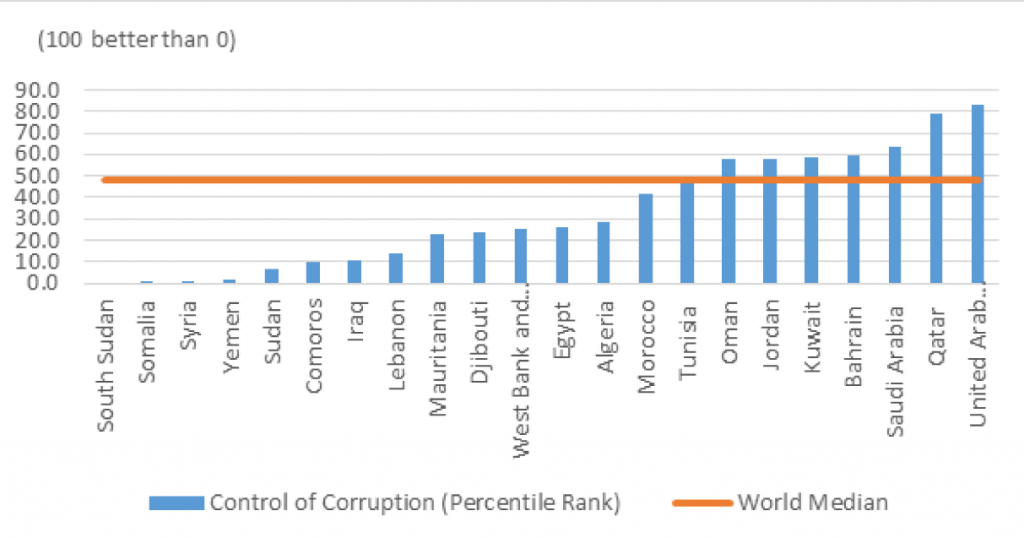

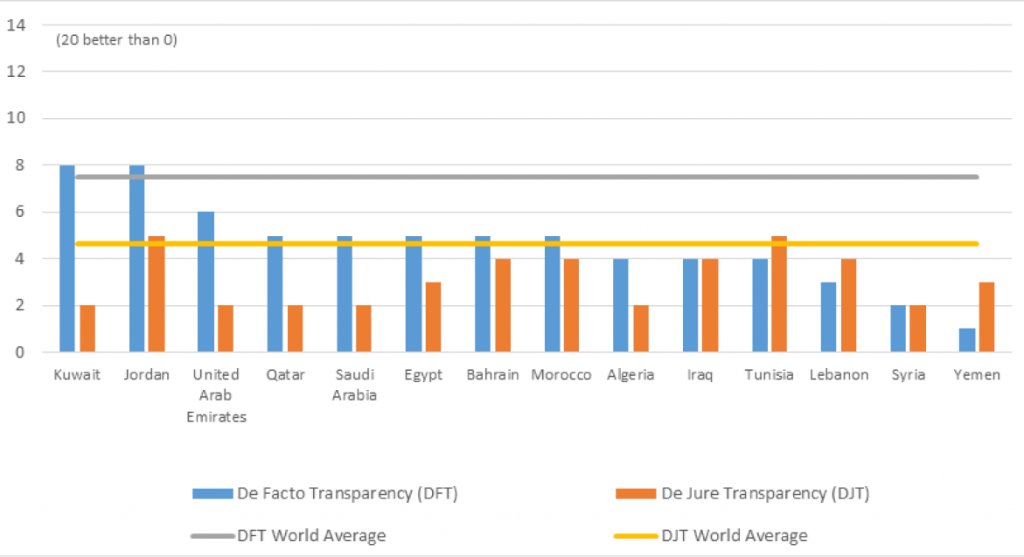

The revised GPA includes a new provision that imposes a specific requirement on GPA parties to avoid conflicts of interest and corrupt practices (Anderson et al, 2016). The governance indicators reveal that Arab countries are in a relatively backward position and suffer great deviation relative to rest of the world as well as among themselves (see Figures 1 and 2). Hence, joining the GPA can be a way to improve the governance framework in Arab countries.

Figure 1: Control of corruption indicator in Arab countries, percentile rank (2022)

https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

Figure 2: Transparency index in selected Arab states (2023)

Note: The new Computer Mediated Government Transparency Index (T-Index) produced by ERCAS in 2021 measures transparency as the existence of accessible (free of cost) public information required to deter corruption and enable public accountability in a society. The De Jure index reviews legal transparency (a country’s transparency legislation), and de the De Facto Index rates 14 essential websites for the coverage and accessibility of data. The 14 websites were selected using the categories of transparency described in the United Nations Convention (UNCAC) against Corruption and Sustainable Development Goal16.

Conclusions

Joining the GPA is not a panacea for Arab countries. The political will for reform and the desire to fight corruption could act as strong incentives for current regimes to join the GPA as a way to achieve such goals. But joining the GPA in itself might not help if the surrounding business and investment environment is not ready, and the human capacity concerned with implementation of the GPA remains reluctant to do so.

Hence, joining the GPA with its flexible provisions should be prudently applied by the implementing agencies in Arab countries to ensure that they serve development purposes and are not hijacked by special interests.

Political will is of paramount importance to ensure that flexibility is not abused and that the GPA helps to achieve transparency in the procurement process and provides a level playing field for competition. In this regard and for acceding to the GPA to be useful for Arab countries, there is a need to revisit the related rules and regulations, especially those dealing with investment disputes. Moreover, there is a need to amend the related government procurement laws to be compliant with the GPA.

Finally, the institutional set-up governing procurement must be revised to ensure common practice by all implementing agencies and reduce the discretion provided to the contracting agencies in their own jurisdictions.

Further reading

Anderson, Robert D (2010) ‘The WTO Agreement on Government Procurement: An emerging tool of global integration and good governance’, EBRD Law in Transition Autumn 2010.

Anderson, Robert D, Claudia Locatelli, Anna C Müller and Philippe Pelletier (2014) ‘The Relationship between Services Trade and Government Procurement Commitments: Insights from Relevant WTO Agreements and Recent RTAs’, WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2014-21.

Anderson, Robert D, and Anna C Müller (2020) ‘Keeping markets open while ensuring due flexibility for governments in a time of economic and public health crisis: The role of the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement’, Public Procurement Law Review 29(4).

Anderson, Robert D, Anna C Müller and Bill Kovacic (2016) ‘Promoting Competition and Deterring Corruption in Public Procurement Markets: Synergies with Trade Liberalization’, paper presented at E15 Expert Group on Competition Policy and the Trade System, ICTSD, World Economic Forum.

Anderson, Robert D, Philippe Pelletier and Kodjo Osei-Lah (2011) ‘Assessing the value of future accessions to the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA): Some new data sources, provisional estimates, and an evaluative framework for individual WTO members considering accession’, WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2011-15.

Bosio, Erica, and Simeon Djankov (2020) ‘How Large is Public Procurement?’

Chakravarthy, S, and Kamala Dawar (2011) ‘India’s possible accession to the Agreement on Government Procurement: What are the pros and cons?’, chapter 4 in S Arrowsmith and RD Anderson (eds) The WTO Regime on Government Procurement: Challenge and Reform, Cambridge University Press.

Chen, Hejing, and John Whalley (2011) ‘The WTO Government Procurement Agreement and Its Impacts’, NBER Working Paper No. 17365.

EBRD, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (2012) Global Practice Guide: Public Procurement, prepared by Lex Mundi.

EBRD, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (2013) Public Procurement Sector Assessment: Review of Laws and Practice in the SEMED region – Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia.

ITC, International Trade Centre (2023) WTO Government Procurement Agreement: A Gender Lens for Action.

Modaffari, Fortunata Giada (2023) ‘The Procurement Law in the Middle East’, Scholars International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice.

Shreiber, Bernd, Raymond Khoury and Lokesh Dadhish (2020) ‘Public Procurement Transformation in the GCC Region: Post Covid 19 Era’, Arthur Little.

Shingal, Anirudh (2011) ‘Foreign market access in government procurement’, paper presented at the 13th annual conference of the European Trade Study Group, 8-10 September 2011, University of Copenhagen.

Shingal, Anirudh (2015) ‘Internationalization of government procurement regulation: The Case of India’, EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2015/86.

WTO, World Trade Organization (2024) Agreement on Government Procurement. Yukins, Christopher R, and Johannes S Schnitzer (2015) ‘GPA Accession: Lessons Learned on the Strengths and Weaknesses of the WTO Government Procurement Agreement’, Trade Law & Development Journal 89.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.