In a nutshell

The Sudan Labor Market Panel Survey 2022 – which is the country’s first nationally representative survey since 2014 – provides substantial opportunities for researchers to develop a better understanding of the evolution of Sudan’s labour market, economy and society.

The survey consists of a household questionnaire and an individual questionnaire for those aged five and older; the resulting data – which were collected from June to September 2022 by Sudan’s Central Bureau of Statistics and ERF – include 4,878 households and 25,442 individuals.

The absence of a nationally representative labour market or household survey for almost a decade has meant that policy-makers have faced major barriers to making evidence-based decisions.

There has not been a nationally representative labour market or household survey in Sudan for almost a decade. This means that, until recently, policy-makers and researchers have faced major barriers to making evidence-based decisions.

The Sudan Labor Market Panel Survey (SLMPS) 2022 is the country’s first nationally representative survey since 2014. The survey includes household and individual information on geographical location, housing conditions, employment status and history, household enterprises, wages and sources of income, education, marital status, time use and more. The survey also includes people in refugee camps, IDP (internally displaced people) camps, refugee areas and IDP areas.

The SLMPS, which offers publicly available data, provides substantial opportunities for researchers to develop a better understanding of the evolution of Sudan’s labour market, economy and society.

Long-standing challenges for Sudan

Sudan has experienced a series of crises and shocks since 2018. The country has not been able to achieve structural transformation, and it has been experiencing declining productivity and rising poverty for some time (Etang Ndip and Lange, 2019).

Long-standing economic challenges contributed to the protests in 2018, leading to the eventual ousting of President Al-Bashir in 2019. While the formation of a civilian government later in the year brought a moment of global re-engagement, the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 was a major setback for the Sudanese economy (Central Bureau of Statistics, CBS, and World Bank, 2020), and one that was then compounded by rapid inflation (Asare et al, 2020; CBS and World Bank, 2020).

Political instability, including the military coup in October 2021, continued into 2022, in conjunction with further economic woes. Most recently, in April 2023, open conflict began between the armed forces and Rapid Support Forces.

Throughout this period, there have been limited data available to understand the state of Sudan’s labour market, economy and society. Like much of the MENA region, Sudan is a ‘data desert’ (Das et al, 2013; Ekhator-Mobayode and Hoogeveen, 2021). The most recent preceding household surveys in Sudan were in 2014, and the most recent labour force survey in 2011 (Ebaidalla and Satti, 2021; Ministry of Human Resources Development and Labour, 2011), neither of which are publicly available.

About the new data

The SLMPS 2022 is a new, publicly available and nationally representative survey (Krafft, Assaad and Cheung, 2023; OAMDI, 2023). The survey consists of a household questionnaire and an individual questionnaire for those aged five and older. The resulting data include 4,878 households and 25,442 individuals. The data were collected from June to September 2022 by Sudan’s CBS, in collaboration with ERF.

The household questionnaire includes identifiers and household location; a roster of household members; housing conditions and durable assets; current household member migrants abroad; remittances; other income and transfers; shocks and coping mechanisms; non-agricultural enterprises, including information on characteristics, employment of household members and others, assets, expenditures, and revenue; and agricultural assets, land and parcels, capital equipment, livestock, crops, and other agricultural income.

The individual questionnaire includes information about residential mobility; the characteristics of fathers, mothers and siblings (including siblings abroad); health; education level and detailed educational history; training experiences; skills; current employment and unemployment; job characteristics of primary and secondary jobs; labour market history; costs and characteristics of marriage; fertility; women’s employment; wages from primary and any secondary jobs; return migration, refugee and IDP experiences for Sudanese respondents; modules for immigration and refugees for non-Sudanese respondents; information technology; savings and borrowing; attitudes; time use (a full 24-hour diary for adults and a shorter module for children); and a series of questions on rights to parcels, livestock and durables.

The sample

The SLMPS 2022 was a random stratified cluster sample, based on 250 primary sampling units (PSUs). The sample frame was based on remote sensing data population estimates (WorldPop, 2020) in order to create PSUs. This sampling frame was used because there has not been a national population census in Sudan since 2008. The sample frame was complemented by a field listing of households within the PSUs and random sampling.

The strata represented in the sample are:

- Refugee camps

- Refugee areas (areas with non-camp refugee settlements)

- IDP camps

- IDP areas (areas with non-camp IDP settlements)

- Other (non-refugee/non-IDP) rural areas

- Other urban areas

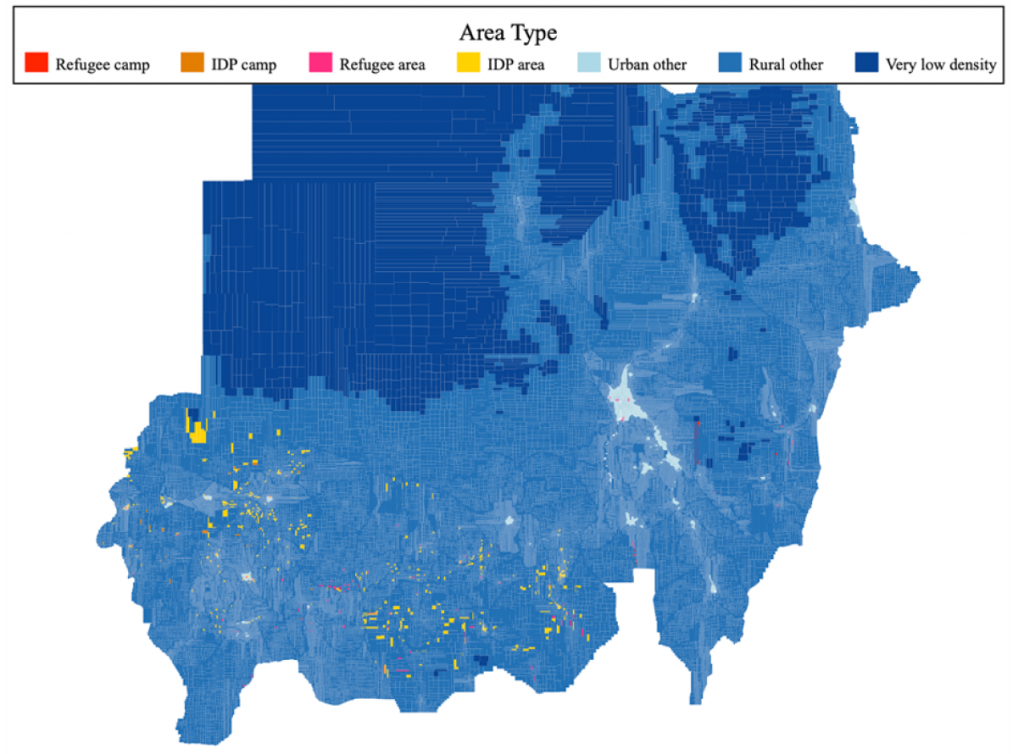

Figure 1 shows the full sample frame of PSUs, classified by the different strata. Sampling weights reflect the sample design, response rates and the national population as of mid-2022 (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, 2022). For more details on the sample design, data collection activities and validation of the sample, see Krafft, Assaad and Cheung (2023).

Figure 1. Full sample frame of PSUs, classified by area type

Source: Authors’ construction based on WorldPop population projections (WorldPop, 2020) and locality boundaries (OCHA Regional Office for Sourthern and Eastern Africa, ROSEA, 2020), data on locations of refugees (OCHA Sudan, 2021) and IDPs (International Organization for Migration, IOM, 2020)

Potential future research

Public-use microdata from the 2022 wave of the SLMPS are available from ERF’s Open Access Microdata Initiative (OAMDI, 2023). While some research on the data has already begun (Assaad, Krafft and Jamkar, 2023; Assaad, Krafft and Wahby, 2023; Krafft et al, 2023a; Krafft, et al, 2023b), the data have enormous potential for additional research. Researchers can request the microdata free of charge from the ERF data portal.

The other waves of LMPSs from Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia are available from OAMDI (Assaad et al, 2016; Krafft and Assaad, 2021; Krafft, Assaad and Rahman, 2021; OAMDI, 2016; 2018; 2019), as well as harmonised datasets across countries.

The rich, publicly available data of the SLMPS provide substantial opportunities for researchers and policy-makers to develop a better understanding of the evolution of Sudan’s labour market, economy and society.

Acknowledgments

SLMPS 2022 was funded with support from the LSMS+ program at the World Bank and the Growth and Labor Markets | Low Income Countries (GLM | LIC) program at IZA, with underlying support from FCDO.

Further reading

Asare, J, S Awad, S Logan, P Mathewson and C Sacchetto (2020) ‘Sudan in the Global Economy: Opportunities for Integration and Inclusive Growth’, International Growth Centre.

Assaad, R, S Ghazouani, C Krafft and DJ Rolando (2016) ‘Introducing the Tunisia Labor Market Panel Survey 2014’, IZA Journal of Labor and Development 5(15): 1-21.

Assaad, R, C Krafft and V Jamkar (2023) ‘Gender, Work, and Time Use in Sudan’, ERF Working Paper series (forthcoming).

Assaad, R, C Krafft and S Wahby (2023) ‘Labor Market Dynamics in Sudan through Political Upheaval and Pandemic’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) and World Bank (2020) Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19 on Sudanese Households.

Das, J, Q-T Do, K Shaines and S Srikant (2013) ‘U.S. and Them: The Geography of Academic Research’, Journal of Development Economics 105(1): 112-30.

Ebaidalla, EM, and SSOM Nour (2021) ‘Economic Growth and Labour Market Outcomes in an Agrarian Economy: The Case of Sudan’, in Regional Report on Jobs and Growth in North Africa 2020 (152-82), International Labour Organization and ERF.

Ekhator-Mobayode, UE, and J Hoogeveen (2021) ‘Microdata Collection and Openness in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA): Introducing the MENA Microdata Access Indicator’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 9892.

Etang Ndip, A, and S Lange (2019) The Labor Market and Poverty in Sudan, World Bank.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2020) ‘Sudan Displacement Data – IDPs [IOM DTM]’, HDX.

Krafft, C, and R Assaad (2021) ‘Introducing the Jordan Labor Market Panel Survey 2016’, IZA Journal of Development and Migration 12(8): 1-42.

Krafft, C, R Assaad and R Cheung (2023) ‘Introducing the Sudan Labor Market Panel Survey 2022’, ERF Working Paper No. 1647.

Krafft, C, R Assaad, A Cortes-Mendosa and I Honzay (2023a) ‘The Structure of the Labor Force and Employment in Sudan’, ERF Working Paper No. 1648.

Krafft, C, T Kilic and H Moylan (2023b) ‘Women’s Economic Empowerment in Sudan: Assets and Agency’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Krafft, C, R Assaad and KW Rahman (2021) ‘Introducing the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey 2018’, IZA Journal of Development and Migration 12(12): 1-40.

Ministry of Human Resources Development and Labour (2011) Sudan Labour Force Survey 2011.

OAMDI (2016) Labor Market Panel Surveys (LMPS), Version 2.0 of Licensed Data Files; TLMPS 2014, ERF.

OAMDI (2018) Labor Market Panel Surveys (LMPS), Version 1.1 of Licensed Data Files; JLMPS 2016, ERF.

OAMDI (2019) Labor Market Panel Surveys (LMPS), Version 2.0 of Licensed Data Files; ELMPS 2018.

OAMDI (2023) Labor Market Panel Surveys (LMPS), Version 2.0 of Licensed Data Files; SLMPS 2022.

OCHA Regional Office for Sourthern and Eastern Africa, ROSEA (2020) ‘Sudan – Subnational Administrative Boundaries – Humanitarian Data Exchange’, HDX.

OCHA Sudan (2021) ‘UNHCR Refugee Camps – Humanitarian Data Exchange’, HDX.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2022) ‘World Population Prospects: The 2022 Revision‘. WorldPop (2020) ‘Sudan – Population Counts – Humanitarian Data Exchange‘, HDX.