In a nutshell

The Sudan Labor Market Panel Survey (SLMPS) 2022 reveals a steady decline in men’s participation in the labour force and a sudden drop in women’s participation; these may reflect the worsening economic conditions in the country over recent years.

In the aftermath of numerous recent shocks, Sudan’s labour market faces several challenges; demographic pressures on labour supply, difficulties with enrolment and gender inequality in participation are long-standing issues that may have been exacerbated by the decade of crises.

Creating decent work for Sudan’s young and growing population has become even more challenging; ending the conflict and stabilising the security and political situation will be essential pre-requisites for addressing wider economic and labour market challenges.

Since Sudan’s last labour force survey in 2011, the country has been beset by a series of shocks (Ministry of Human Resources Development and Labour, 2011). Over the past decade, the country has experienced revolution, political turmoil and the Covid-19 pandemic (Central Bureau of Statistics, CBS, and World Bank 2020; Asare et al, 2020), as well as the recent outbreak of conflict in April 2023.

Rapid inflation and negative economic growth in Sudan have been well-documented (World Bank 2023). But until now, the impacts of the shocks and crises on households and the labour market have remained largely unknown.

The Sudan Labor Market Panel Survey (SLMPS) 2022 (OAMDI, 2023; Krafft, Assaad and Cheung, 2023) provides an important opportunity to understand how Sudan’s labour market has responded to these shocks. Using the new survey data, this column discusses the evolution of Sudan’s population; marriage and fertility trends; educational composition; labour force participation; employment and unemployment rates; and the structure of employment (based on Krafft et al, 2023).

Sudan has a young and growing population

Sudan has a large youth population, with 63% of its population aged 24 and younger. Early marriage is common for women, as 30% of women aged 15-59 in the SLMPS married before the age of 18. The median age at marriage was 20 for women and 29 for men. This early marriage is one contributor to Sudan’s high fertility rate. The data show the total fertility rate to be 4.9 births per woman – the same rate as in 1999.

Education remains less than universal

Nearly half of adults aged 25-64 (49%) are illiterate in Sudan – 39% of men and 58% of women. A substantial fraction of adults can read and write but have not completed any level of formal schooling. A further 14% have attained less than secondary level, with just 13% attaining secondary (with fewer women than men doing so). About a tenth of adults have attained higher education, with a slightly higher share among women than men. Rural women are particularly unlikely to have completed school.

In 2022, net enrolment rates (the percentage of those of primary age enrolled in primary education and likewise for secondary education) were 56% for primary school and 23% for secondary school. Net enrolment rates estimated from the SLMPS 2022 are higher for girls (58% primary, 27% secondary) than boys (55% primary, 20% secondary), and they are higher in urban areas (80% primary, 48% secondary) than in rural areas (48% primary, 12% secondary).

Declining labour force participation and employment

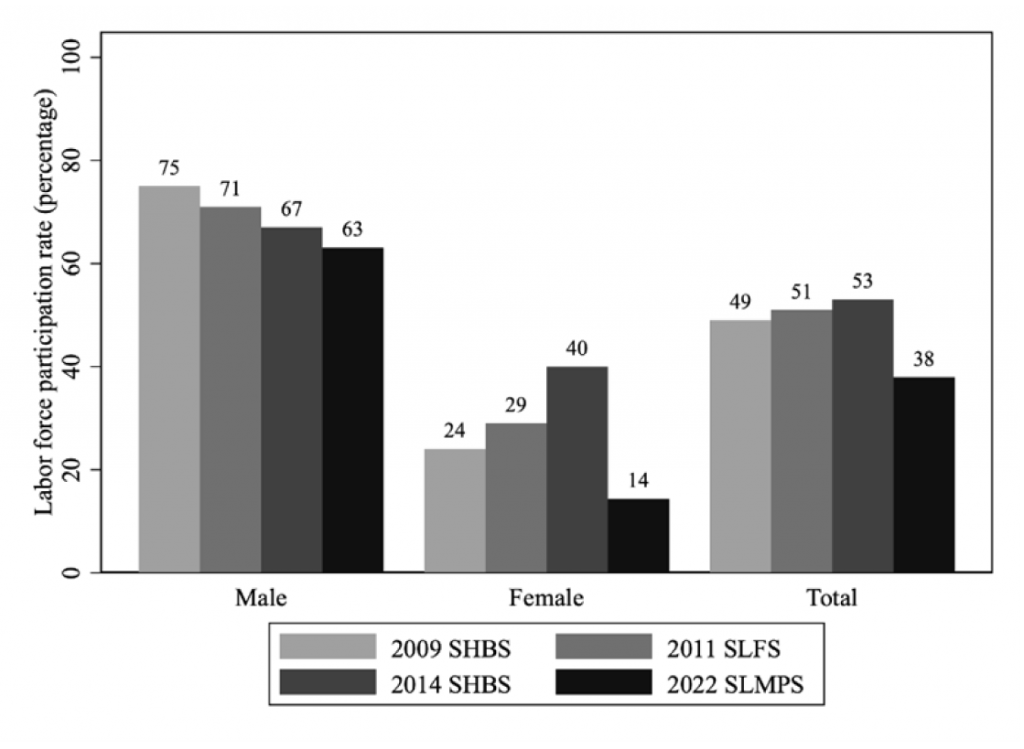

Sudan’s labour force participation rate was 38% in 2022 (63% for men, 14% for women). Over time (see Figure 1), there has been a decline in men’s labour force participation. In contrast, there had been a steady increase in women’s participation before the SLMPS 2022.

The rate estimated for men in 2009 was 75%, but this fell to 71% in 2011 and 67% in 2014, such that the rate of 63% in the SLMPS 2022 is in line with the trend (Krafft, Nour and Ebaidalla, 2022; Krafft, Assaad and Cheung, 2023). Participation had been rising for women prior to the SLMPS 2022: from 24% in 2009 to 29% in 2011 and 40% in 2014 (Krafft, Nour and Ebaidalla, 2022; Krafft, Assaad and Cheung, 2023). But in 2022, the participation rate for women was just 14%.

The steady decline in men’s participation in the labour force and the sudden drop in women’s participation may reflect the worsening economic conditions in Sudan. The decline in women’s participation may also reflect women being more infrequently involved in market work or working in family businesses. Particularly for rural women, such participation often goes under-detected by standard measures of participation (Assaad, Krafft and Jamkar, 2023; Assaad and Krafft, 2023).

Figure 1: Labour force participation rate (percentage of individuals aged 15-64), by sex and data source

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the SLMPS 2022, Sudan Census 2008, and report with SHBS 2009, SLFS 2011, and SHBS 2014/15 statistics (Ebaidalla and Nour, 2021).

Notes: Market employment, standard, search-required, 7-day reference period definition used for the SLMPS 2022.

Employment and unemployment

Changes in labour force participation can reflect shifts in employment or unemployment. Both employment rates and unemployment rates are lower in the SLMPS 2022 than in earlier surveys. Employment rates fell from 42% in 2014 to 35% in 2022 – from 60% to 59% for men; and from 26% to 12% for women. Standard unemployment rates also fell from 20% to 8% – falling from 11% to 7% for men; and from 34% to 15% for women (Krafft, Assaad and Cheung, 2023).

But there are much higher rates of both employment and unemployment when broader definitions are used – for example, when using annual measures of employment that include participation detected from family businesses, or when including the discouraged unemployed (Krafft et al, 2023; Assaad, Krafft and Jamkar, 2023).

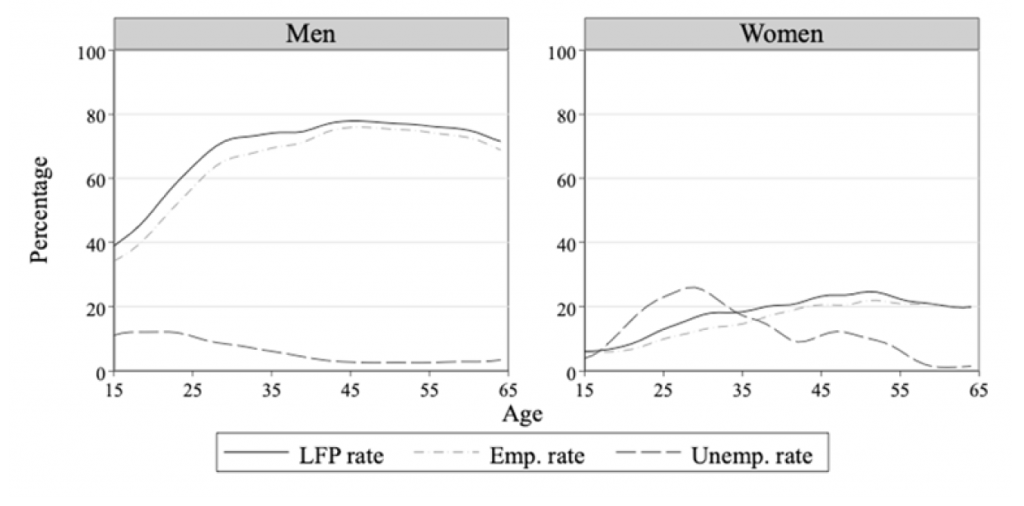

While there are only moderate differences in labour market outcomes by education (as other research has noted – see Ebaidalla and Nour, 2021; Krafft, Nour and Ebaidalla, 2022), there are clear life-cycle patterns of labour force participation (see Figure 2).

For men, participation increases sharply between the ages of 15 (from just below 40%) and 25 (slightly below 70%), with more modest increases until a peak at almost 80% at the age of 45. Rates drop slightly to a bit above 70% by the age of 64.

For women, participation is low (less than 10%) at the age of 15. Participation rises with age, with women’s participation peaking around 25% just before the age of 55, then falling slightly to 20% by the age of 64.

Figure 2: Labour force participation rate (percentage of the population), employment rate (percentage of the population), and unemployment rate (percentage of the labour force), ages 15-64, by sex and age, 2022

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the SLMPS 2022

Unemployment is primarily a youth phenomenon, particularly among men. Unemployment rates for men are above 10% from the age of 15 until around 25, and then they decline steadily between the ages of 25 and 45 to reach a very low level at older ages. Women’s unemployment rises substantially with age, from below 10% at the age of 15 to a peak of just over 25% at around 30.

Employment remains in agriculture, non-wage work and informal wage work

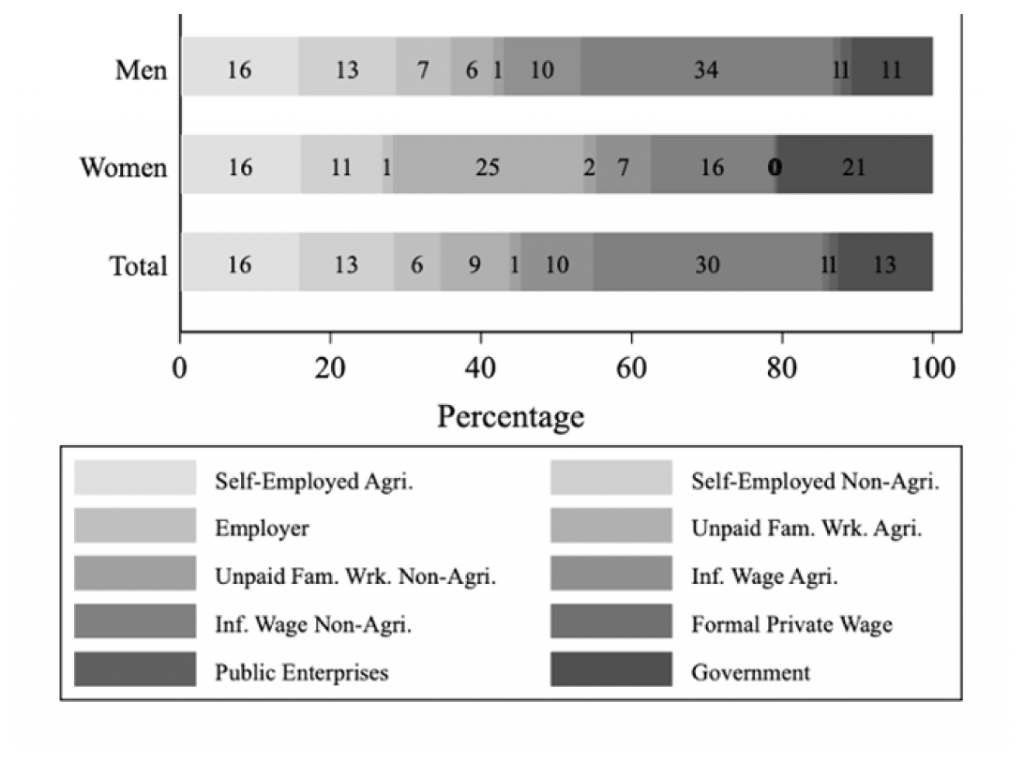

Sudan’s economy has experienced limited structural transformation. The country has long been dominated by agriculture, non-wage work and informal wage work (Ebaidalla and Nour, 2021; Etang Ndip and Lange, 2019).

In 2022, this continues to be the case (see Figure 3). A sizeable share of employment is self-employment, including 16% in agriculture and 13% in non-agriculture. A further 6% of workers are employers of others. Unpaid family work is most common in agriculture (9%) but it is rare in non-agricultural sectors (1%). A further 10% of employment is in informal wage work in agriculture and 30% of employment in informal wage non-agricultural industries.

Overall, 39% of employment is in agriculture, although this share increases if definitions other than current market employment are considered. There is very little formal private sector wage work (1%) or public enterprise work (1%), but 13% of employment is in government.

Figure 3. Distribution of employment (percentage) by institutional sector, location, and sex, employed individuals ages 15-64, 2022

Shocks and the future of Sudan’s labour market

In the aftermath of the numerous shocks in the period before the SLMPS 2022, Sudan’s economy and labour market face several challenges. Demographic pressures on labour supply, difficulties with enrolment and gender inequality in participation are long-standing issues that may have been exacerbated by the decade of crises.

Creating decent work for Sudan’s young and growing population has become even more challenging in 2023. Ending the conflict and stabilising the security and political situation will be essential pre-requisites for addressing wider economic and labour market challenges. Additional data collection and research are needed to understand the impact of the recent conflict on Sudan’s society and economy, and to inform efforts trying to ameliorate some of its harms.

Further reading

Asare, J, S Awad, S Logan, P Mathewson and C Sacchetto (2020) ‘Sudan in the Global Economy: Opportunities for Integration and Inclusive Growth’, International Growth Centre.

Assaad, R, and C Krafft (2023) ‘Connecting People to Projects: A New Approach to Measuring Women’s Employment in the Middle East and North Africa’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series (Forthcoming).

Assaad, R, C Krafft and V Jamkar (2023) ‘Gender, Work, and Time Use in Sudan’, ERF Working Paper series (forthcoming).

Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) and World Bank (2020) Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19 on Sudanese Households.

Ebaidalla, EM, and SMN Satti (2021) ‘Economic Growth and Labour Market Outcomes in an Agrarian Economy: The Case of Sudan’, in Regional Report on Jobs and Growth in North Africa 2020 (152-82), International Labour Organization and ERF.

Etang Ndip, A, and S Lange (2019) The Labor Market and Poverty in Sudan, World Bank.

Krafft, C, R Assaad and R Cheung (2023) ‘Introducing the Sudan Labor Market Panel Survey 2022’, ERF Working Paper No. 1647.

Krafft, C, R Assaad, A Cortes-Mendosa and I Honzay (2023) ‘The Structure of the Labor Force and Employment in Sudan’, ERF Working Paper No. 1648.

Krafft, C, SSOM Nour and EM Ebaidalla (2022) ‘Jobs and Growth in North Africa in the COVID-19 Era The Case of Sudan (2018-21)’, in Second Regional Report on Jobs and Growth in North Africa (2018-21): Developments through the COVID-19 Era, ERF and ILO.

Ministry of Human Resources Development and Labour (2011) Sudan Labour Force Survey 2011.

OAMDI (2023) Labor Market Panel Surveys (LMPS), Version 2.0 of Licensed Data Files, SLMPS 2022.

World Bank (2023) Sudan Macro Poverty Outlook.