In a nutshell

Fragmented labour markets in the countries of the Middle East and North Africa offer limited opportunities for successful job entry and career mobility to the vast majority of workers.

Young people and women have struggled to find decent employment despite high rates of educational achievement; their prospects for transition to formal jobs have eroded over the past decade, squandering valuable human capital.

Governments should broaden access to vocational and life-long learning, create conditions for streamlining worker mobility, and bridge the gaps between informal and formal jobs, including providing support for businesses in the process of formalising.

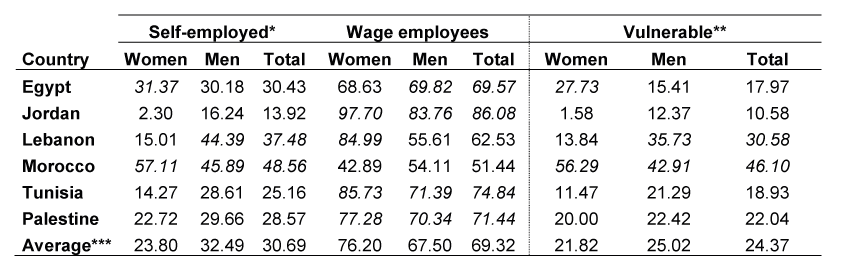

Our recent study (Adair et al, 2022) has documented pervasive market segmentation, informal employment, low occupational mobility, and ubiquity of micro and small-size informal businesses operating in low-productivity industries across six lower-middle-income, oil-importing MENA economies (Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia in North Africa; and Jordan, Lebanon and Palestine in the Middle East). The share of informal employment has been highest in Morocco and lowest in Tunisia. Self-employment largely overlaps with informal and most vulnerable forms of work, such as own-account workers who are men, and contributing family workers or casual/irregular workers who are women (see Table 1).

Table 1: Distribution of workforce status and vulnerability by gender in MENA countries (2019)

Notes: * includes employers, own-account workers and contributing family workers. ** Some self-employed (excluding employers) as a percentage of total employment. *** Figures in italics are above average.

Source: Authors’ compilation of modelled estimates in the ILOSTAT.

Women’s labour force participation in MENA has persistently been the lowest of all world regions, and rose only slowly and unevenly between 2000 (19%) and 2019 (20%). The labour market participation rate is over twice as high for young men (54.5%) than for youth women (23.1%), while one-quarter of the labour force is unemployed, disproportionately affecting women. Two in three young men are informal workers in North Africa as of 2015, compared with one in three young women (Adair and Gherbi, 2023).

This high prevalence of informality without social protection among young people is consistent with a U-shaped lifecycle pattern: informality declines from youth to maturity and rises again among the pre-retirement group.

Drivers of poor occupational outcomes and mobility

The shortage of decent jobs may be partly attributed to reduced staffing in the regional public sectors, and the state of duality in the private sector whereby the predominant informal businesses struggle financially competing with the well-connected high-productivity formal enterprises.

The observed dearth of workers’ transitions out of informality indicates that informal employment is not driven by choice on the labour supply side but by structural demand-side flaws.

Transition tables and probability regressions estimated on longitudinal microdata reveal that workers’ starting job, and parents’ characteristics, including their education, occupation and wealth, have a lasting effect on workers’ outcomes. This suggests that rigid non-skill-based hiring and promotion policies, waste and discrimination may be rampant among private sector employers.

The consequence is that the private sector is squandering substantial human capital, with repercussions for labour productivity, innovation and growth.

Social and solidarity economy

At a time when public employment is on the decline, the ‘social and solidarity economy’ (SSE) may help to fill the void in decent employment. The SSE includes both for-profit and non-profit entities, cooperatives and other associations, and it recruits workers from underrepresented segments of society.

The success of the SSE hinges on adequate initial capitalisation. Personal savings and grants presently constitute the major funding sources, which are subject to structural deficiencies in the banking system and lack tailored financial products. External backing is thus warranted.

Policy recommendations

Traditional formalisation policies targeting businesses and workers with various stick and carrot strategies have had modest impacts on underemployment and informality. Innovative approaches are needed to stimulate decent job creation, to tackle the fragmentation of MENA labour markets, and to promote occupational mobility and human capital development.

Formalisation should target both informal businesses and workers, combining incentives and penalties. SSE enterprises, including microfinance institutions (MFIs), should back the formalisation drive of informal enterprises. Standing as a benchmark, the Alexandria Business Association, an Egyptian MFI, successfully tripled the number of fully formalised clients between 2004 (6%) and 2016 (18%).

Public policies should contribute, including specific tax and public procurement policies addressing informal workers who are establishing or joining formal sustainable organisations.

Formalisation efforts would support formalising of existing occupations and creating an adequate number of new decent jobs. Even before relevant reforms can be implemented, governments should deepen the support systems for workers who are presently excluded or face precarious working conditions. Ultimately, this will foster a more sustainable and inclusive trajectory of economic development.

Finally, on the monitoring side, formalisation policies encapsulate distinct target setting and impact assessment, which should be conducted according to their prospective effects on decent employment and labour use within formal sustainable organisations.

Tracking informality requires both thorough investigation and taking stock of stylised facts. Labour market surveys disrupted by the Covid-19 and financial crises must resume data collection for assessment of labour market trends, and as a pre-requisite for formalisation policies.

Further reading

Adair, Philippe (2022) ‘Policies addressing the formalisation of informality in North Africa: Issues and outcomes’, proceedings of The Informal Economy and Gender Inequalities International Conference, Bejaia University, Algeria, June 2021, Revue d’études sur les institutions et le développement 97-110.

Adair, Philippe, and Hassiba Gherbi (2022) ‘The Youth Gender Gap in North Africa: Income Differentials and Informal Employment’, Maghreb-Mashrek International 1-2: 151-67.

Adair, Philippe, Vladimir Hlasny, Mariem Omrani and Kareem Sharabi Rosshandler (2022) ‘Fostering the Social and Solidarity Economy and Formalizing Informality in MENA Countries’, ERF Working Paper No. 1604.

AlAzzawi, Shireen, and Vladimir Hlasny (2022) ‘Youth Labor Market Vulnerabilities: Evidence from Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia’, International Journal of Manpower 43(7): 1670-99.