In a nutshell

Economic institutions can predict integration into the global value chain (GVC) in MENA countries: forward linkages rise with property rights and business freedom, suggesting a suitable business environment for inputs used in third countries’ exports.

Backward linkages increase with business freedom and decline with government integrity, suggesting that imported intermediates used in exports are substituted by increasing domestic goods as a result of better integrity in government procedures, leading foreign value-added to decline.

GVC participation rises with property rights and business freedom, and declines with government integrity, which seems to be driven by the backward linkages component.

Participation in the global value chain (GVC) is increasing at an unprecedented rate, with growing trade liberalisation, reduced transport and communication costs, and advances in technologies. Integration into the GVC enables firms to benefit from lower labour costs, as the distribution of comparative advantages criss-crosses countries and slices down their production into tasks performed in different locations (Grossman and Rossi Hansberg, 2008; Feenstra and Hanson, 1997).

Participation in the GVC makes it possible to gauge the extent to which economies are involved along the supply chain, and thus allows tracing and mapping the distribution of value-added along supply chains. The process of production is fragmented depending on the production processes with two slants in a form of the ‘snake’, where intermediate inputs are processed sequentially, or the ‘spider’, wherein intermediate inputs are processed in no order.

Despite the benefits of GVC participation, the associated gains are unevenly distributed across the world. Most of the value-added originates in capital- and labour-intensive production activities fundamentally carried out in developed economies and some developing countries such as East Asia and Latin America, while the low-skill production activities associated with low value-added are carried out in developing countries based on specialisation.

Research shows that GVC trade is determined by a number of factors, including geographical location, firm size, productivity, foreign direct investment (FDI) and technological capabilities (Dollar et al, 2016; Mohamedou, 2021). But the associations between economic institutions and GVC trade remain insufficiently explored.

Here, we shed some light on the importance of economic institutions as a key determinant of the extent to which economies are integrated into the GVC for 13 MENA countries, with a particular focus on foreign value-added in a country’s exports (backward linkages), exports of intermediates used in third countries’ exports (forward linkages) and variables measuring GVC participation.

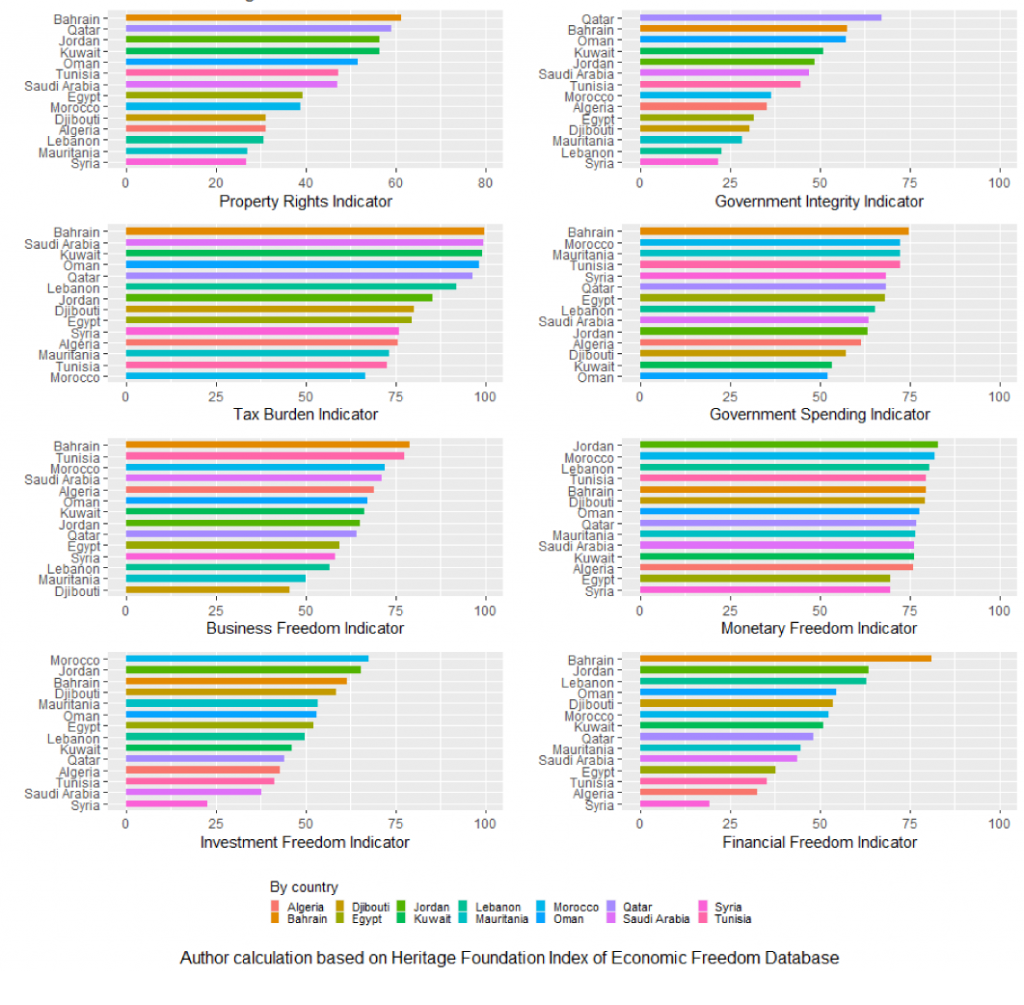

Figure 1: 2000-2018 Average Economic Institutions Indicators

Source: Mohamedou (2022)

Figure 1 depicts the average scores of economic indicators for the 13 MENA countries. Bahrain is leading the MENA countries when it comes to the scores for property rights, government integrity, tax burden, government spending, and business and financial freedom, whereas Syria is lagging.

Associations between scores on economic institutions and GVC-related variables

My research examines the association between eight economic institutions’ scores and three variables that measure the extent of GVC participation.

The findings show that economic institutions are significantly linked to GVC participation by the MENA countries and that the association is dynamic in nature.

Forward linkages increase not only with the score for business freedom but also with the score for property rights. Business freedom and property rights promote a favourable environment of domestic productivity and technological progress, which leads to the volume of exported goods used in other countries’ exports rising, suggesting higher forward linkages.

Higher scores for businesses and monetary and financial freedom make it more convenient for firms to do business freely and to expand their activities through the import of intermediates used in their exports as well as promoting FDI.

Higher scores for government integrity and investment freedom diminish restrictions on investments while strengthening domestic production. This leads to a diminishing reliance on imported intermediates used in a country’s exports – that is, domestic intermediates tend to substitute imported intermediates used in the exports and therefore, declining forward linkages.

The results suggest that a favourable business environment promotes firms’ productivity, technological development, and learning by doing, enabling upgraded integration into the GVC via the import of intermediates used in a country’s exports, while the negative association with government integrity prevails.

Finally, business freedom and property rights promote GVC participation. Government integrity remains negatively associated with GVC participation, which seems to be mainly driven by the effect of the backward linkages.

Economic institutions play a central role in explaining changes in participation in the GVC. These findings imply that MENA countries should grant more freedom to businesses, monetary and financial institutions as well as property rights to promote integration into the GVC and to maximise the gains associated with such integration.

Further reading

Dollar, D, Y Ge and X Yu (2016) ‘Institutions and participation in global value chains’, (Global Value Chain Development Report Background Paper), World Bank.

Feenstra, RC, and GH Hanson (1997) ‘Foreign direct investment and relative wages: Evidence from Mexico’s maquiladoras’, Journal of International Economics 42(3-4): 371-93.

Grossman, GM, and E Rossi-Hansberg (2008) ‘Trading tasks: A simple theory of offshoring’, American Economic Review 98(5): 1978-97.

Mohamedou, Nasser Dine (2022) ‘Impact of Economic Institutions on Participation in the Global Value Chain: Evidence from the MENA Countries’.

Mohamedou, Nasser Dine, and Tengku Menawar Chalil (2021) ‘Impact of Backward Linkages and Domestic Contents of Exports on Labor Productivity and Employment: Evidence from Japanese Industrial Data’, Journal of Economic Integration 36(4): 607-25.