In a nutshell

Decent work was a challenge for North African labour markets even pre-pandemic, with high unemployment, high informality and low labour force participation of women; economic difficulties associated with Covid-19 created further challenges for those who had been working or seeking work.

There was a sharp initial contraction in employment in the second quarter of 2020, during the strictest lockdown; key labour market aggregates, such as employment, tended to recover soon thereafter, but to varying degrees across countries.

Other indicators – such as hours of work and incomes – show more persistent negative effects; informal workers, farmers and the self-employed tended to be the most affected by the pandemic, but did not necessarily receive the most social assistance.

Countries in North Africa had struggled to provide decent work in the decade leading up to the pandemic (International Labour Organization, ILO, and ERF, 2021). This column discusses the new challenges the pandemic brought in ensuring decent work for all in the region. It focuses on Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia – and, to the extent possible (given that the country’s last official labour force survey was in 2011), Sudan.

The underlying research (ILO and ERF, 2022; Krafft et al, 2022b) is based on official growth and labour market statistics, and data through mid-2021 from the COVID-19 MENA Monitor (ERF’s Open Access Micro Data Initiative, OAMDI, 2021 – where data are publicly available).

Employment dropped and unemployment rose at the start of the pandemic

The pandemic led to drops in employment in Q2 of 2020, right at the onset of lockdowns and economic contractions (see Figure 1). For example, the employment rate in Egypt fell from 41.0% to 36.7% from Q1 to Q2 of 2020. In some cases, recovery was swift. For example, the employment rate in Egypt rose to 39.8% in Q3 of 2020 and was 42.0% by Q4 of 2020.

The employment decline was relatively small initially in Tunisia: from 44.6% to 42.6%. Nevertheless, Tunisia struggled with recovery, with employment rising to 43.9% in Q3 2020 before continuing to fall to 42.0% in Q3 of 2021.

Morocco’s challenges occurred with some lag, with employment dropping from 41.2% in Q1 2020 to 39.3% in Q2 2020, and then 38.0% in Q3 2020. But this drop may also be related to agricultural cyclicality.

As employment fell at the onset of the pandemic, unemployment rose overall. But there were important divergences by gender and country.

Unemployment rose particularly for men in Egypt (but followed employment trends in recovering promptly). For Egyptian women, unemployment did not rise, but their labour force participation fell. Women’s employment rates did, however, recover to pre-pandemic levels fairly quickly, and unemployment trended gradually up over time as women restarted searching for jobs. In contrast, in Morocco and Tunisia, women and men’s unemployment trends were broadly similar.

Time-related underemployment – also known as involuntary part-time work – is the share of the employed working fewer than 35 hours per week due to lack of work. This can be a better indicator of labour market health than unemployment (Assaad, 2019), as workers engaged in casual, intermittent labour may have some work, and thus not be unemployed, but be facing substantial underemployment.

Underemployment data are not available for Tunisia and are only available for Egypt in Q4 of every year. But in Morocco, and comparing Egypt’s Q4 in 2019 to 2020, it is clear that time-related underemployment rose over time. Indeed, in Egypt, while unemployment recovered to pre-pandemic levels quickly, underemployment did not.

Figure 1: Labour force participation rate (percentage of the population), employment rate (percentage of the population), unemployment rate (percentage of the labour force), and time-related underemployment rate (percentage of the employed)

Notes: Time-related underemployment is only available in Q4 in Egypt and not available in Tunisia.

Source: Official labour statistics (ILO and ERF, 2022).

Informal workers were particularly affected during the pandemic

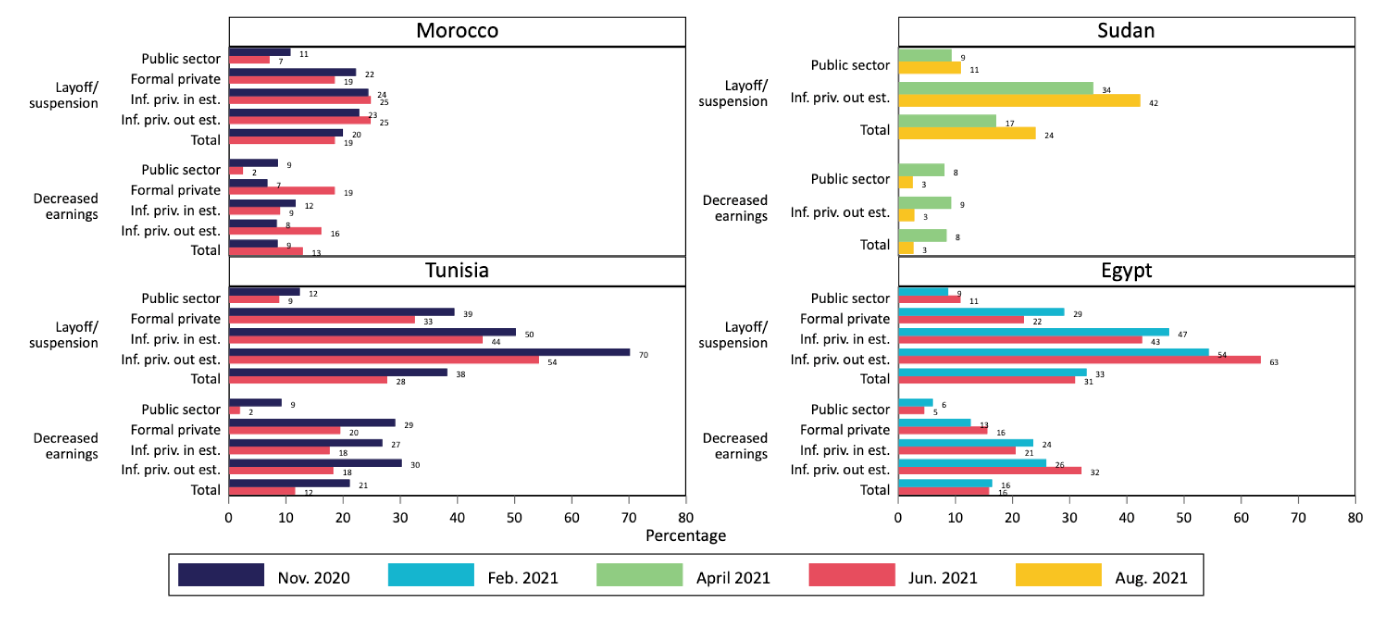

Drawing on COVID-19 MENA Monitor data, Figure 2 illustrates the challenges experienced by individuals who were wage workers in February 2020, prior to the pandemic. It reveals differences by sector, formality (social insurance) and whether a worker worked in or outside a fixed establishment. Among wage workers, informal private sector workers tended to be the most affected by layoffs and decreased earnings, particularly those outside establishments.

For example, in Tunisia, in November 2020, 70% of those who were (in February 2020) informal private sector wage workers working outside establishments reported layoffs or suspensions in the past 60 days. Differences overall were smaller in Morocco and for earnings in Sudan (where inflation may have led to fewer decreases in nominal earnings).

In Egypt, informal wage workers working outside establishments were particularly likely to report decreased earnings in June 2021 (32%), even more than a year after the pandemic began. Other analyses focused on the self-employed and farmers show that these groups also particularly struggled during the pandemic (Assaad et al, 2022; Krafft et al, 2022b; Marouani et al, 2022).

Figure 2: Percentage of wage workers laid off or with decreased earnings, by type of employment (in February 2020), wave and country

Note: For panel respondents, challenges were only available if they were still wage workers. Categories with fewer than 50 observations (in Sudan) are not shown. Figure shows only first and latest waves

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on COVID-19 MENA Monitor.

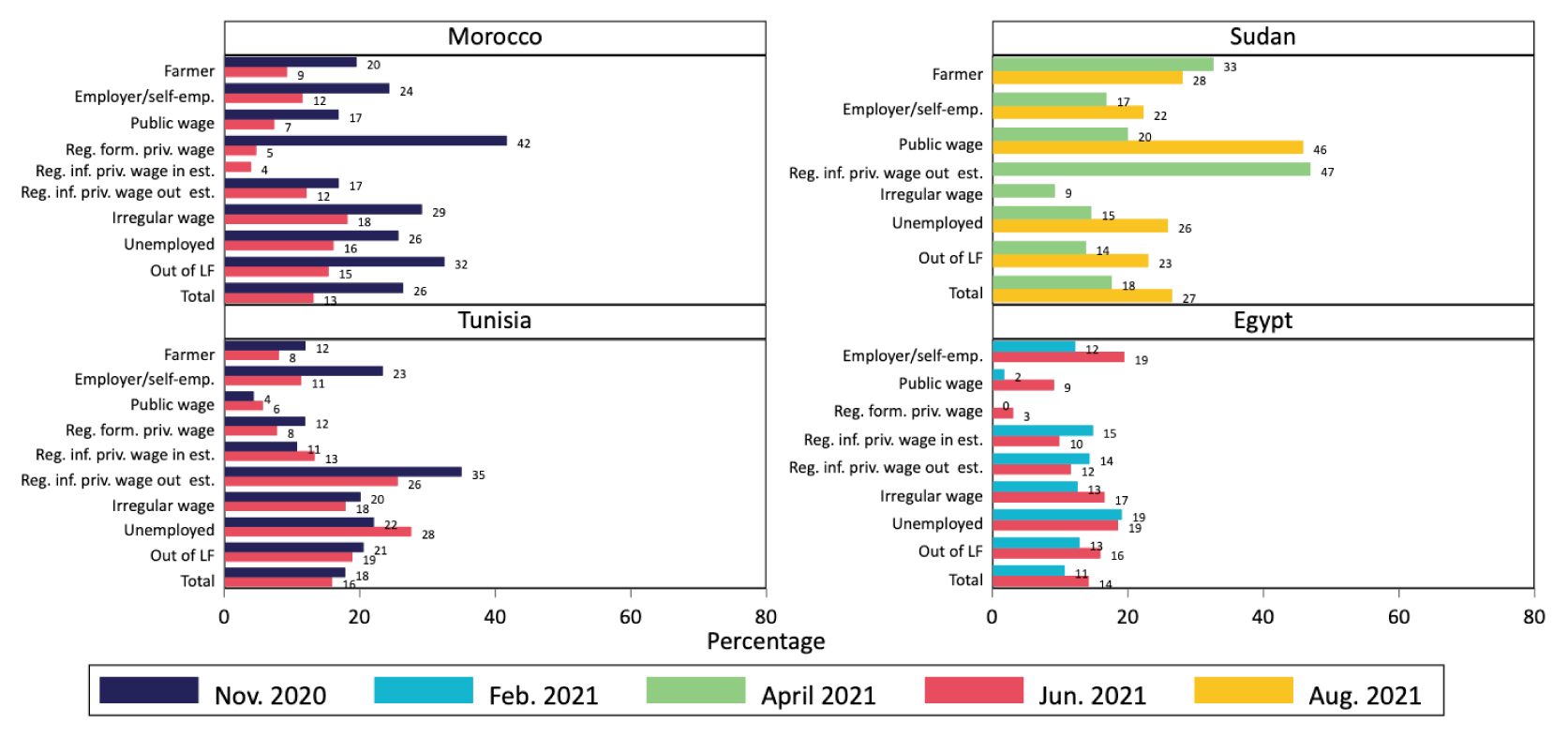

There were substantial efforts by North African governments to ameliorate the impact of the pandemic, including by expanding existing social assistance programmes and creating new ones. Figure 3 shows the percentage of individuals in households that received government assistance, by their labour market status in February 2020 (first and latest waves). (Regular assistance was only asked about at baseline; emergency assistance programmes were asked about for the past month.)

Regular versus irregular work is further distinguished, since some policies specifically targeted irregular workers. Notably, social assistance decreased over time in Morocco and Tunisia, but increased in Sudan and Egypt. Targeting was weak; those groups, such as informal wage workers, who were particularly affected, were only sometimes more likely to receive assistance. The self-employed and farmers also were not unusually likely to receive assistance.

Figure 3: Receiving government assistance (percentage), by labour market status in February 2020 and by country, first and latest waves

Note: Categories with fewer than 50 observations are not shown.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on COVID-19 MENA Monitor.

Robust and shock-responsive social protection

The fallout of the pandemic has highlighted the importance of having a robust and shock-responsive social protection system in place. Expanding pre-existing social protection programmes or funnelling additional funds through such programmes were the main avenues for pandemic assistance in North Africa (Assaad et al, 2022; ILO and ERF, 2022; Krafft et al, 2022b; Marouani et al, 2022).

Creating new social programmes when shocks occur is unlikely to be timely. Ensuring that systems and data are in place to identify all households and their potential vulnerability to shocks is an important precursor for rapidly expanding existing programmes during shocks.

Countries also need to plan for shock-responsive systems even when there is limited fiscal space. North African countries spent a lower share of GDP on responding to the pandemic than the global average (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD, 2021), possibly due to constrained fiscal space.

Social protection systems need to expand their coverage to include informal economy workers, particularly farmers and the self-employed, who are often outside the reach of the contributory, social insurance system, making assistance and targeting difficult.

Ensuring all households have some form of social protection in the face of shocks will be a continuing challenge for social protection systems in the region. Future shocks may take different forms, such as the Russia-Ukraine conflict contributing to food shortages and inflation. The fundamental challenge for current and future shocks is ensuring that families can meet their basic needs. Responding to this challenge requires a broad, shock-responsive social protection system.

References

Assaad, Ragui (2019) ‘Moving beyond the Unemployment Rate: Alternative Measures of Labour Market Outcomes to Advance the Decent Work Agenda in North Africa’, ILO and ERF.

Assaad, Ragui, Caroline Krafft, Mohamed Ali Marouani, Sydney Kennedy, Ruby Cheung and Sarah Wahby (2022) ‘Egypt COVID-19 Country Case Study’, ILO/ERF Report.

ILO and ERF (2021) ‘Regional Report on Jobs and Growth Report in North Africa 2020’.

ILO and ERF (2022) ‘Second Regional Report on Jobs and Growth in North Africa (2018 -2021): Developments through the COVID-19 Era’.

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Mohamed Ali Marouani (2022a) ‘Jobs and Growth in North Africa during the COVID-19 Pandemic’, ERF Policy Brief No. 97.

Krafft, Caroline, Mohamed Ali Marouani, Ragui Assaad, Ruby Cheung, Ava LaPlante, Ilhaan Omar and Sarah Wahby (2022b) ‘Morocco COVID-19 Country Case Study’, ILO/ERF Report.

Marouani, Mohamed Ali, Caroline Krafft, Ragui Assaad, Sydney Kennedy, Ruby Cheung, Ahmed Dhia Latifi and Emilie Wojcieszynski (2022) ‘Tunisia COVID-19 Country Case Study’, ILO/ERF Report.

OAMDI (2021) ‘COVID-19 MENA Monitor Household Survey’ (CCMMHH); Version 5.0 of the Licensed Data Files; CCMMHH_Nov-2020-Aug-2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

OECD (2021) ‘Fiscal Monitor: Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic’.