In a nutshell

Although employment rates dropped during the initial lockdown phase of the pandemic in the second quarter of 2020, they had generally recovered by mid-2021 in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Sudan and Tunisia; similarly, wage inequality initially rose but shifted back to pre-Covid-19 levels.

Hours of work tended to decline overall from late 2020 to mid-2021, a shift that is likely due to informal and self-employed workers, who had lost employment initially and tend to work fewer hours, later returning to work.

Employment during the recovery has depended on labour market status and sector pre-pandemic: public sector followed by private formal sector workers were the most likely to stay employed, while non-wage and informal private sector wage workers were more likely to exit employment.

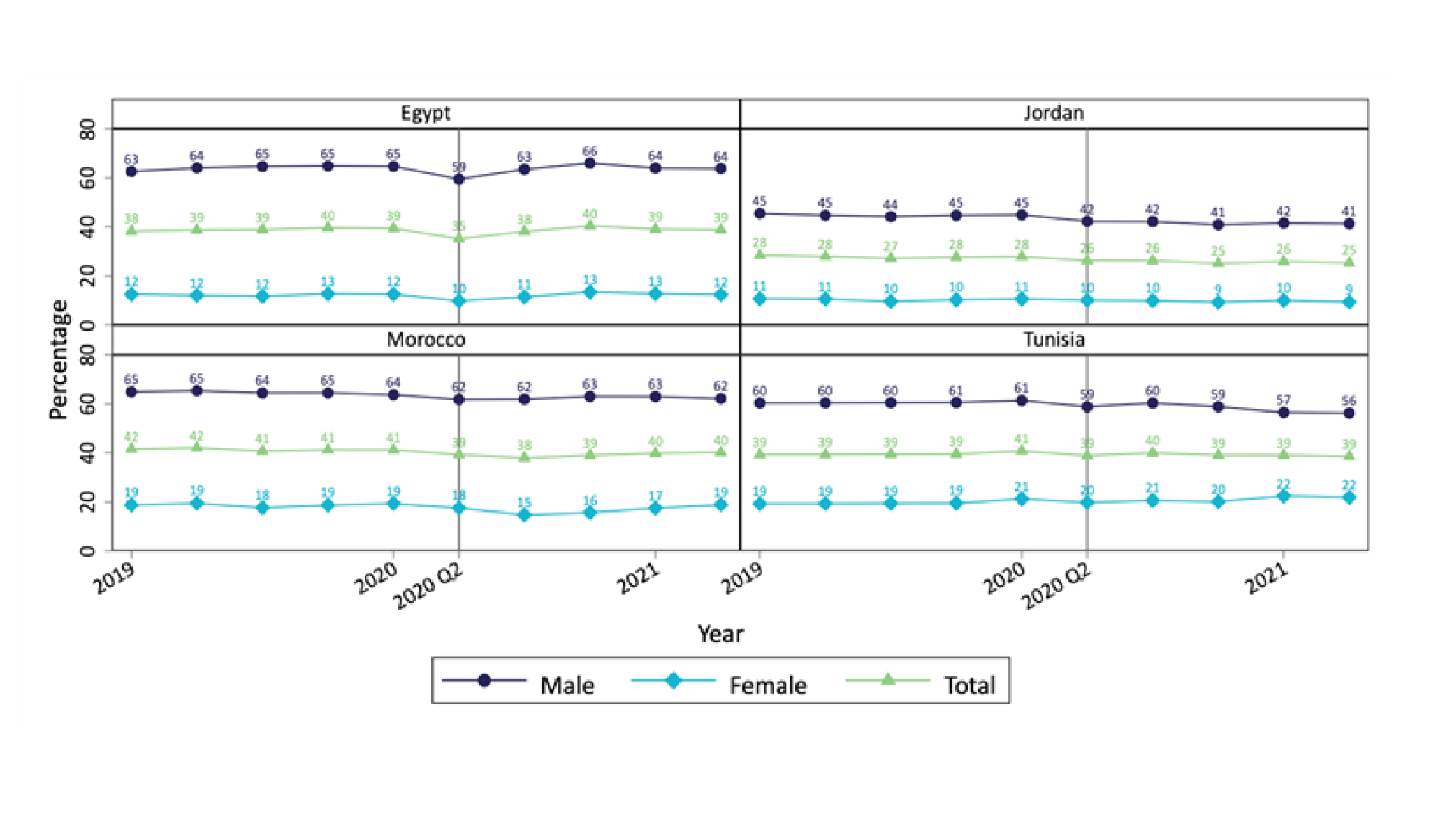

As in many parts of the world, employment rates in the MENA region initially fell in the second quarter of 2020, with the onset of the pandemic (see Figure 1, calculated based on official statistics). For example, in Egypt, the overall employment rate fell from 39% in the first quarter of 2020 to 35% in the second quarter of 2020.

But employment recovery in most cases was fairly swift, for example, rising back to 38% in Egypt by the third quarter of 2020. Women’s employment rates, which were already low before the pandemic, generally followed a similar pattern to men’s and the overall downturn and recovery.

Wage inequality initially rose during the pandemic, with some recovery

One concerning potential impact of the pandemic and its associated economic effects, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, is increasing poverty and inequality (World Bank, 2020; Acevedo et al, 2022). Previous research has established substantial declines in income comparing pandemic-era income with pre-pandemic income in MENA, declines that particularly affected the poor and exacerbated inequality (Krafft et al., 2021a; 2021b; 2022).

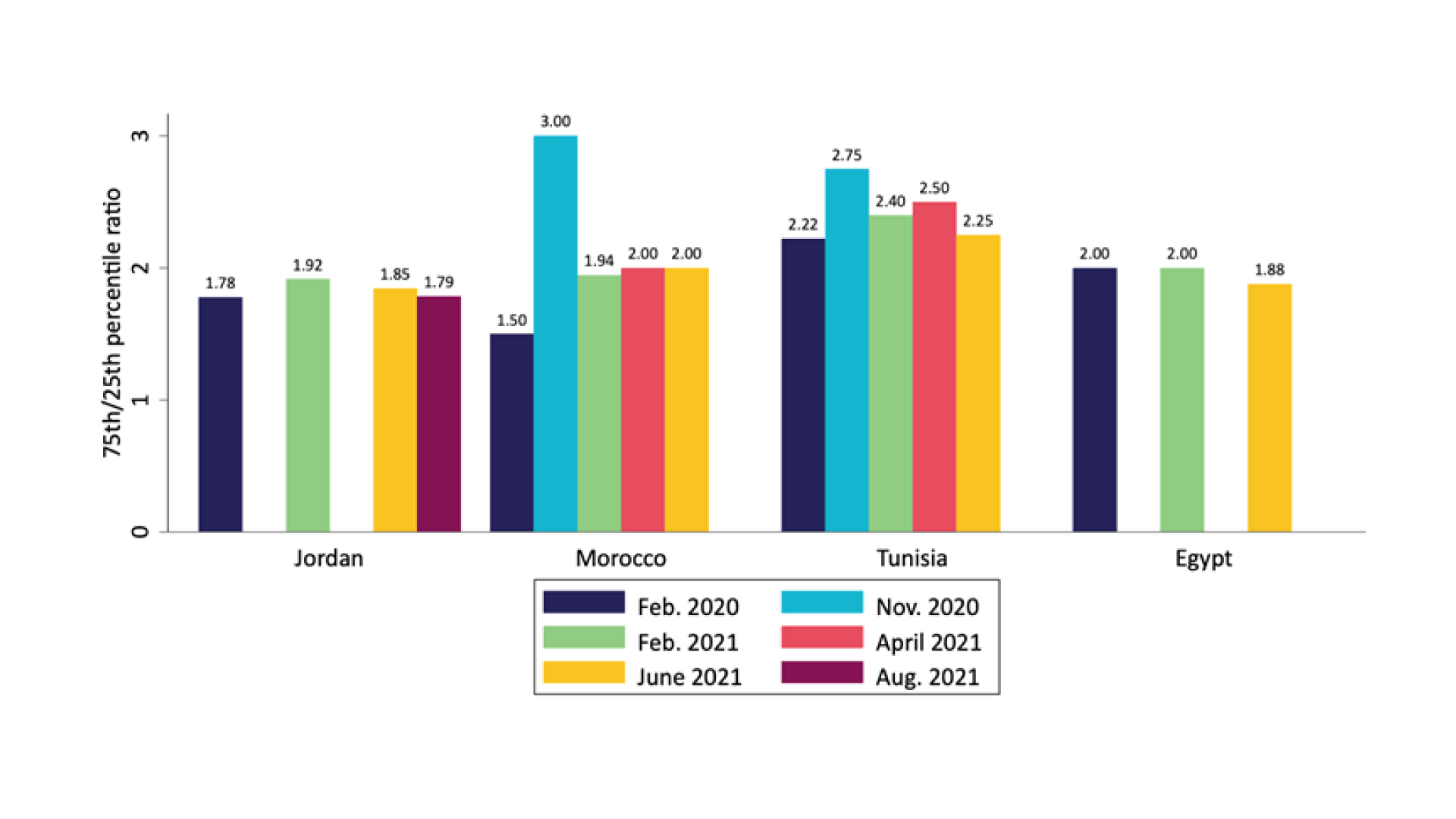

Figure 2 explores the 75th/25th percentile ratio (p75/25) to show how monthly wage inequality has evolved since before the pandemic (in February 2020) through the waves of the COVID-19 MENA monitor (OAMDI, 2021). Inequality initially rose but then, in most cases, recovered to at or near pre-pandemic levels.

For example, in Tunisia, the p75/p25 ratio was 2.22 pre-pandemic, rose to 2.75 by November 2020 (the first wave of COVID-19 MENA monitor data), and then fell to 2.40 in February 2021, 2.50 in April 2021 and back to nearly pre-pandemic levels, 2.25, in June 2021. Although initial increases in inequality may have dissipated, their long-term impacts and impacts on poverty remain an important question for future research.

Figure 1: Employment rates (percentage), by country, sex and quarter, 2019-2021

Source: Krafft et al. (2022) based on country’s official quarterly labour force survey bulletins.

Notes: Since employment rates are not consistently reported, we calculate the employment rate (e) based on the labour force participation rate (l) and unemployment rate (u) by using the following formula: e=l(1-u). Tunisia labour force participation rates for 2019 are annual rather than quarterly.

Figure 2: 75th/25th percentile ratio of monthly wages, by country and wave

Source: Krafft et al. (2022) based on COVID-19 MENA monitor.

Labour market adjustments occurred in hours and wages

Research examining labour market status, hours of work and hourly wages highlights how a number of important dimensions of pandemic-era labour market adjustment have evolved over time (Krafft et al., 2022).

Those who were public sector and private sector formal wage workers before the pandemic were less likely to exit employment in most countries. While some of this pattern may be a continuation of pre-pandemic patterns of employment transitions by type of work (Assaad et al., 2022), workers who were informal private sector wage workers were particularly likely to report temporary or permanent layoffs (Krafft et al., 2021a).

Self-employed workers and small firms also tended to report income losses and reduced hours of operation (Krafft et al., 2021a, 2021c). As these workers returned to employment, average hours of work fell, but this seems to be due to the changing mix of workers rather than reductions in hours among workers who were employed (Krafft et al., 2022).

Looking within specific groups of workers, such as those who were non-wage workers pre-pandemic, hours were stable or tended to rise in most countries over time (Krafft et al., 2022). Hourly wages were relatively stable in Egypt and Jordan, but in countries such as Morocco, followed the same pattern as hours, declining as marginally attached workers returned to employment and increasing when there were decreases in employment.

Policy implications

Variation in policy responses and pre-pandemic economic structures has shaped the nature of labour market adjustments during the pandemic, with some important lessons for recovery efforts and future crises. Both Egypt and Jordan experienced relatively more labour market stability (Krafft et al., 2022).

In Egypt’s case, the economic impact of the pandemic was limited due to somewhat less stringent lockdown policies. Egypt even had a positive economic growth rate in 2020: 1.5% (Ministry of Planning and Economic Development 2021). Note that Egypt reports official statistics for a fiscal year spanning July to June; we have adjusted statistics to present calendar years here, for comparability to other countries.

Jordan had a relatively more stable labour market trajectory as well, despite a worse economic situation than Egypt, due to a variety of factors including a relatively less tourism-dependent economy, policies to prevent layoffs and a relatively more formal labour market before the pandemic (Krafft et al., 2022).

Morocco and Tunisia had more severe economic contractions and labour market volatility during the recovery, which may be related to variable but often stringent lockdowns (Krafft et al., 2022). Both Morocco and Sudan, which have a high share of employment in agriculture, were dealing with agricultural cyclicality at the same time as Covid-19 adjustments, increasing volatility (Krafft et al., 2022). Sudan was also dealing with a number of economic policy and political challenges, such as exchange rate devaluation, protests and political instability (Advancing the Decent Work Agenda II Report, 2022 forthcoming).

The pandemic has underscored how pre-existing structural challenges, such as gaps in the social safety net, can leave those most vulnerable to shocks, such as informal workers, with limited recourse (Krafft et al., 2021a; Krafft et al., 2022). Social safety nets that are crisis-responsive and include informal workers and the working poor are critical to ameliorating future shocks.

Note: This column is based on ‘Employment and Care Work during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Persistent Inequality in the Middle East and North Africa’, ERF Policy Brief No. 78 by Caroline Krafft, Ilhaan Omar, Ragui Assaad, Ruby Cheung, Ava LaPlante, Mohamed Ali Marouani, Irene Selwaness and Maia Sieverding. The underlying research is detailed in ‘Are Labour Markets in the Middle East and North Africa Recovering from the COVID-19 Pandemic?’, ILO/ERF Working Paper by Caroline Krafft, Ragui Assaad, Mohamed Ali Marouani, Ruby Cheung and Ava LaPlante.

Further reading

Acevedo, Ivonne, Francesca Castellani, Maria José Cota, Giulia Lotti and Miguel Székely (2022) ‘Higher Inequality in Latin America: A Collateral Effect of the Pandemic’, IDB Working Paper Series No. 01323.

Advancing the Decent Work Agenda II Report (2022, forthcoming), ILO and ERF.

Assaad, Ragui, Abdelaziz AlSharawy and Colette Salemi (2022) ‘Is The Egyptian Economy Creating Good Jobs? Job Creation and Economic Vulnerability from 1998 to 2018’, in The Egyptian Labor Market: A Focus on Gender and Vulnerability edited by Caroline Krafft and Ragui Assaad, Oxford University Press.

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Mohamed Ali Marouani (2021a) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle Eastern and North African Labor Markets: Glimmers of Progress but Persistent Problems for Vulnerable Workers a Year into the Pandemic’, ERF Policy Brief No. 57.

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Mohamed Ali Marouani (2021b) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle Eastern and North African Labor Markets: Vulnerable Workers, Small Entrepreneurs, and Farmers Bear the Brunt of the Pandemic in Morocco and Tunisia’, ERF Policy Brief No. 55.

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Mohamed Ali Marouani (2021c) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle Eastern and North African Labor Markets: A Focus on Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises’, ERF Policy Brief No. 60.

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Mohamed Ali Marouani (2022) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle Eastern and North African Labor Markets: Employment Recovering, but Income Losses Persisting’, ERF Policy Brief No. 73.

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad, Mohamed Ali Marouani, Ruby Cheung and Ava LaPlante (2022) ‘Are Labour Markets in the Middle East and North Africa Recovering from the COVID-19 Pandemic?’, ILO/ERF Working Paper.

Krafft, Caroline, Irene Selwaness and Maia Sieverding (2022) ‘The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women’s Care Work and Employment in the Middle East and North Africa. ILO/ERF Working Paper.

Ministry of Planning and Economic Development (2021) Gross Domestic Product, accessed 2 September 2021.

OAMDI (2021) ‘COVID-19 MENA Monitor Household Survey (CCMMHH)’, Version 5.0 of the Licensed Data Files; CCMMHH_Nov-2020-Aug-2021, retrieved 30 November 2021.

World Bank (2020) Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune.