In a nutshell

Education plays a key role in shaping individuals’ outcomes when it comes to better labour market transitions: for example, the better educated are more likely to make a transition from the informal private sector to the formal sector, and out of inactivity or unemployment into employment.

Essential labour market reforms include policies favouring women’s participation in the labour market: the provision of childcare services; the promotion of women-friendly working environment; and potentially imposing hiring quotas for women.

The continuing Covid-19 crisis calls for high-frequency labour market data to assess the impact of the pandemic on labour markets; representative longitudinal panel data are needed to understand labour market outcomes during and after of the pandemic.

The Covid-19 crisis constitutes a major shock to labour markets the world over. In advanced countries and a number of middle-income countries, systematic evidence on the impact of the pandemic on labour markets has become increasingly available thanks to high-frequency surveys, the availability of administrative data and longitudinal panels.

Globally, the emerging evidence points to important impacts on youth employment, increased drop-outs from the labour force, and losses of jobs, wages and incomes, especially among informal, casual and domestic workers. There is also a significant impact on women’s employment given their over-representation in the healthcare sector and higher demand on their care work (ILO, 2020; Weber and Newhouse, 2021).

But due to lack of data in large parts of the developing world and especially in the Middle East and North Africa, our understanding of the impact of Covid-19 on those labour markets is still limited.

A snapshot of the labour market

To assess the impact of Covid-19 on labour markets, it is necessary to understand the functioning of those labour markets prior to the shock, preferably over the long run. We create this comparison by studying labour market dynamics in Egypt over two decades. Focusing on the prime working age population (adults between the ages of 20 and 59), we show snapshots of the Egyptian labour market using four rounds of cross-sectional data from the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS).

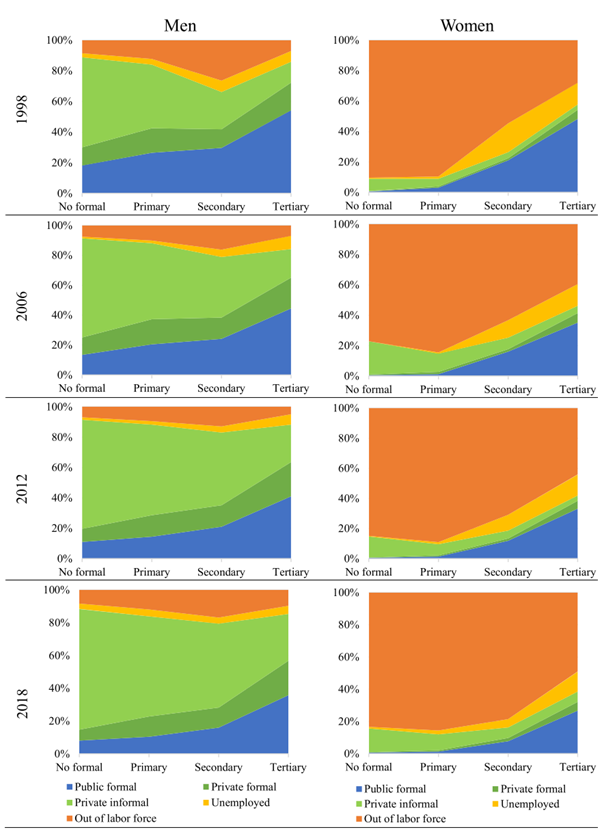

Figure 1 shows several findings. First, while most men participate in the labour market irrespective of their educational level, only women with post-secondary education do so significantly. Indeed, the share of women who are out of the labour force is always large, and it has actually increased between 1998 and 2018.

Figure 1: Employment status and sector among those aged 20-59, by education

Notes. The analysis relies on cross-sectional data from the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) in 1998, 2006, 2012 and 2018. We focus on individuals aged between 20 and 59 years old in each survey round. We rely on the market definition of work status, search required (reference 1 week). Expansion weights are used.

Second, public sector employment has declined over the past two decades among both women and men. The decline coincides with an increase in the size of the private informal sector.

It is important to note that while Egypt’s large informal sector is similar in size to that of other middle-income countries such as Mexico and Colombia – accounting for approximately 60% of total employment (Lanau et al, 2018; Gurria, 2019) – Egypt has a much larger public sector. In 2020, Mexico’s public sector accounted for 13% of employment ( ILO and Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo) and Colombia’s just over 4% (ILO and Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares), dwarfed by the Egyptian public sector, which accounted for over a quarter of employment in 2018.

Other comparable countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia also had much smaller public sectors, accounting for 8% and 15% of total employment, respectively (ILO, Malaysia Labor Force Survey and Indonesia National Labor Force Survey).

Third, we find that unemployment rates are consistently higher among the most educated individuals, especially if they are women, although declining over the years.

Finally, we find that the higher the educational level of both men and women, the higher the share of men and women’s employment in the formal sector, be it in the public or private sector, and the lower their engagement in the informal private sector.

Labour market transitions over the life cycle

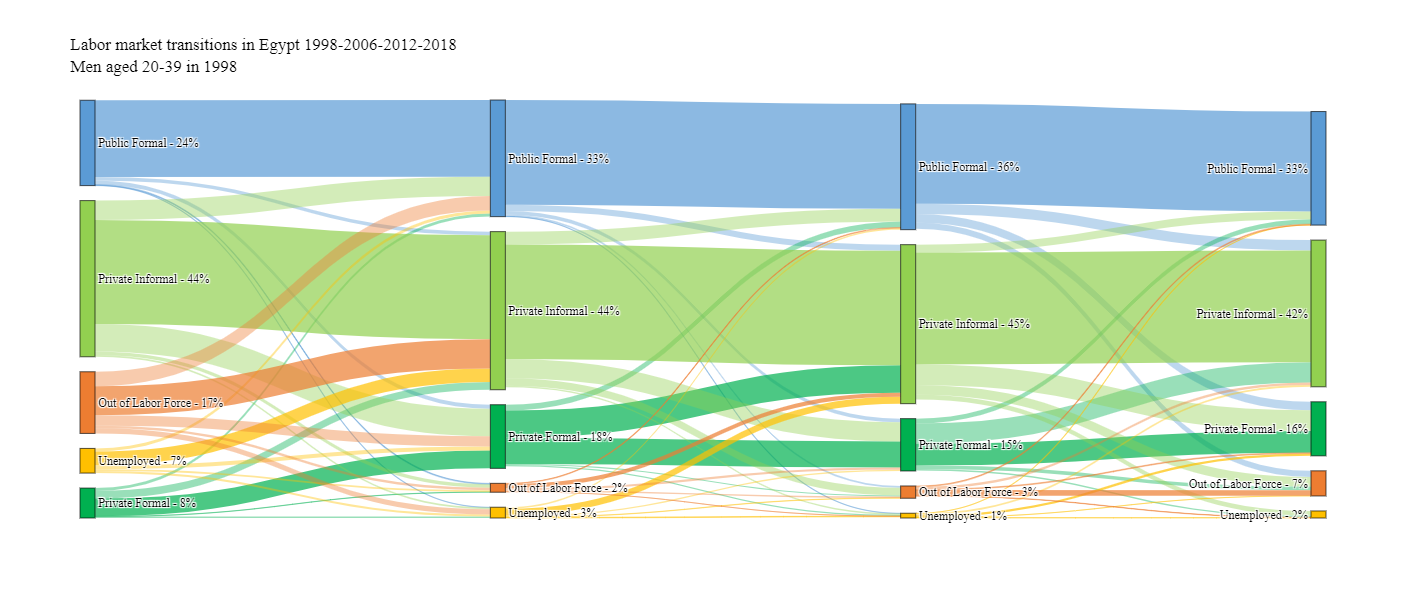

Relying on the panel dimension of the data, we study the evolution of labour market transitions over the life cycle. We follow the same individuals from 1998 to 2018, showing their transitions over four possible labour market states: public sector; private sector (divided into formal and informal); unemployment; and out of the labour force. We look at men and women aged between 20 and 39 years old in 1998 and use interactive Sankey charts to represent the transitions.

At baseline, 24% of men are employed in the public sector, 44% are informally employed in the private sector, and 8% are formally employed in the private sector (see Figure 2). As transitions occur over the life cycle, the share of individuals employed in the public sector grew from 24% in 1998 to 33% in 2018. Indeed, 12% of men informally employed in the private sector, 23% of those out of the labour force, 13% of the unemployed and 10% of those formally employed in the private sector at baseline joined the public sector in 2006.

Figure 2: Employment status and sector among those aged 20-59, by education

Notes: The analysis relies on panel data from the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) in 1998, 2006, 2012 and 2018. We focus on individuals aged between 20 and 39 years old in 1998. We rely on the market definition of work status, search required (reference 1 week). Panel weights are used.

More private sector men workers, whether in the formal or informal sector, continued to make a transition to the public sector over the life cycle. Transitions from the private formal sector to the public formal sector are more frequent, in terms of percentage, as opposed to transitions from the private informal sector to the public sector.

It is also worth noting that transitions within the private sector, between its formal and informal sectors, are much more frequent than those from the private to the public sector. Conversely, those starting in the public sector rarely make a transition to the private formal or private informal sectors, although they are more likely to move to the informal sector than the formal sector over the life cycle.

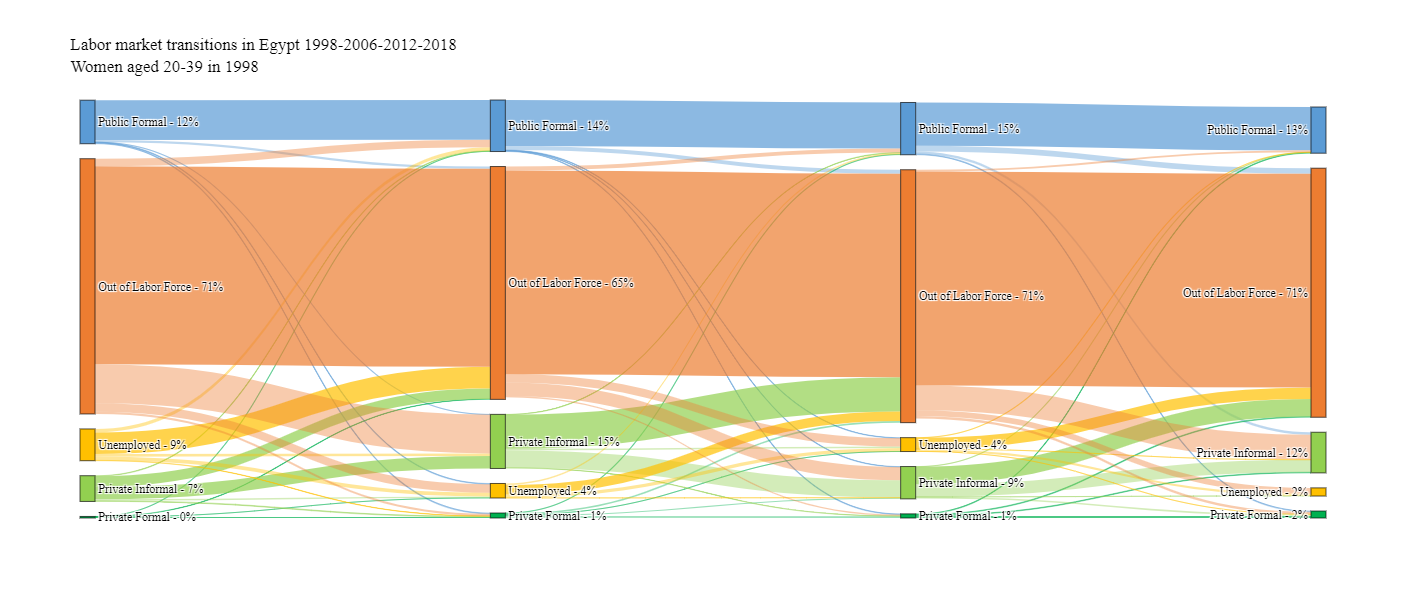

The picture is very different for women (see Figure 3), as the vast majority are out of the labour force both at baseline and at the end of the life cycle (71%). The public sector remains the main employer for women over the life cycle. Indeed, 12% of women at baseline were employed in the public sector, a share that has slightly grown over the life cycle.

Figure 3: Employment status and sector among those aged 20-59, by education

Notes: The analysis relies on panel data from the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) in 1998, 2006, 2012 and 2018. We focus on individuals aged between 20 and 39 years old in 1998. We rely on the market definition of work status, search required (reference 1 week). Panel weights are used.

The life cycle analysis shows that the out of labour force status for women is very persistent: only 3%, 2% and 1% of women out of the labour force in 1998, 2006, and 2012, respectively, managed to make a transition to the public sector by the following round. On the other hand, transitions from out of the labour force to the private informal sector or to unemployment are more likely to occur.

Among women out of the labour force in 1998, 2006 and 2012, respectively 15%, 6% and 10% made a transition to the private informal sector, while 3%, 4% and 2% made a transition to unemployment by the following survey round. Transitions out of the public sector are rare, though we observe women dropping out of the labour force as they aged over our twenty-year window.

Finally, we observe large percentages of women making a transition from the informal private sector to out of the labour force over the life cycle: 41%, 64% and 55% of women informally employed in the private sector in 1998, 2006 and 2012, respectively, dropped out of the labour force in the following wave.

Implications for the aftermath of the pandemic

Our analysis provides important insights on how to address momentous challenges posed by the health crisis. The cross-sectional stock analysis shows that both men and women experienced an increase in economic inactivity over the years. Therefore, the major disruptions associated with the pandemic are further exacerbating pre-existing trends, putting additional pressure on a highly segmented labour market.

Segmentation in the Egyptian labour market is striking across multiple dimensions, notably the gender and sectoral dimensions. The hefty reliance of the Egyptian economy on public sector employment, in particular for women, the small size of the private formal sector, the large and increasing private informal sector, and the very low participation of women in the labour market are all major challenges that make the Egyptian labour market less resilient in absorbing the negative effects of the pandemic.

But there are certainly several lessons that can be learnt from this analysis. Importantly, we note that education plays a key role in shaping individuals’ outcomes when it comes to better labour market transitions. For example, better educated individuals are found to be more likely to make a transition out of the informal private sector into the formal sector, be it in the public or private sector, and out of inactivity or unemployment into employment.

Moreover, better educated women and men are found to be more likely to have formal sector jobs to start, as opposed to the least educated who are more likely to be employed informally. Given that informal workers are typically more vulnerable and bear more severe consequences associated with shocks, safety nets need to be designed to target these vulnerable workers more effectively.

The pandemic brought once again to the policy forefront the need to undertake key essential labour market reforms, such as boosting and supporting job creation in the private formal sector and designing policies favouring women’s participation in the labour market including the provision of childcare services, the promotion of women-friendly working environment and potentially imposing hiring quotas for women.

The continuing crisis also calls for high-frequency labour market data to assess the impact of the pandemic on labour markets. To date, high-frequency phone surveys are the most reliable data source to study the impact of Covid-19 on labour markets in developing countries (Hoogeveen and Lopez-Acevedo, 2021; Krafft et al, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2022).

But phone surveys come with their own caveats. For one, these surveys were conducted only after the pandemic began, which means that one can only control for pre-existing outcomes through self-reported retrospective information.

Another challenge that economists face by design when using phone surveys is the selection of respondents, which are typically not representative of the whole population. Representative longitudinal panel data address both these concerns and are indeed necessary to understand labour market outcomes during and in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Further reading

Gurría, Á (2019) ‘Presentation of the 2019 Economic Survey of Mexico’, OECD.

Hoogeveen, JG, and G Lopez-Acevedo, eds (2021) Distributional Impacts of COVID-19 in the Middle East and North Africa Region, World Bank.

ILO (2020) ‘Rapid Diagnostics for Assessing the Country Level Impact of COVID-19 on the Economy and the Labor Market’.

ILO and Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo (2020) ‘Data on the year of 2020’.

ILO and Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares (2020) ‘Data on the year of 2020’.

ILO, Malaysia Labor Force Survey and Indonesia National Labor Force Survey (2020) ’Data on the year of 2020’.

Krafft, C, R Assaad and MA Marouani (2021a) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle Eastern and North African Labor Markets: Vulnerable Workers, Small Entrepreneurs, and Farmers Bear the Brunt of the Pandemic in Morocco and Tunisia’, ERF Policy Brief No. 55.

Krafft, C, R Assaad and MA Marouani (2021b) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle Eastern and North African Labor Markets: Glimmers of Progress but Persistent Problems for Vulnerable Workers’, ERF Policy Brief No. 57.

Krafft, C, R Assaad and MA Marouani (2021c) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle Eastern and North African Labor Markets: A Focus on Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises’, ERF Policy Brief No. 60.

Krafft, C, R Assaad and MA Marouani (2022) ‘Employment Recovering, but Income Losses Persisting’, ERF Policy Brief No. 73.

Lanau, S, D Rodríguez-Delgado and F Toscani (2018) ‘Colombia Selected Issues’, International Monetary Fund.

Weber, M, and D Newhouse (2021) ‘These types of workers were the most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic’, World Bank blogs, 23 September.