In a nutshell

The effectiveness of entrepreneurship in generating economic development in the MENA region is not related to the number of people in self-employment but to the creative and imitative entry of existing businesses into new markets.

The growth of new businesses is insufficient to stimulate economic growth unless there is a controlled monetary policy as well as good governance quality that supports entrepreneurship in the region.

Self-employment does not support economic growth: it is more of an escape plan out of unemployment and poverty, especially in economies where social institutions are fragile and impractical.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) consists of a heterogeneous group of countries ranging from high-income oil-exporting countries to very poor countries. But this diverse region has shown the highest unemployment rates for over 25 years (Kabbani, 2019), reaching 30% in 2017, and the highest youth population shares in the world.

These two factors have given governments and policy advisers a sense of urgency about creating enough adequate jobs to absorb the incoming flow of young workers. But according to the World Bank 2017, by 2022, over 60% of young people on the MENA market will be working in jobs that have not yet been created. Also, political and economic crises have engulfed large portions of the region since the 2011 Arab Spring, with catastrophic human and economic implications.

Furthermore, the region has seen significant economic and social damages from weak economic governance and wars involving large military outlays (Fardoust, 2016; Cobham and Zouache, 2021). Hence, there is an immediate need to manage the region’s human and financial assets more effectively by implementing economic and social policies to drive the countries to healthier and more equitable economic growth.

Although high levels of unemployment, corruption, lack of government accountability, education and lack of political participation have been crucial issues in the region, it is now imperative that these issues be resolved. In this respect, Ismail et al (2017) assert that these macroeconomic and social situations in the region are the background for a new era of an innovative entrepreneurial economy.

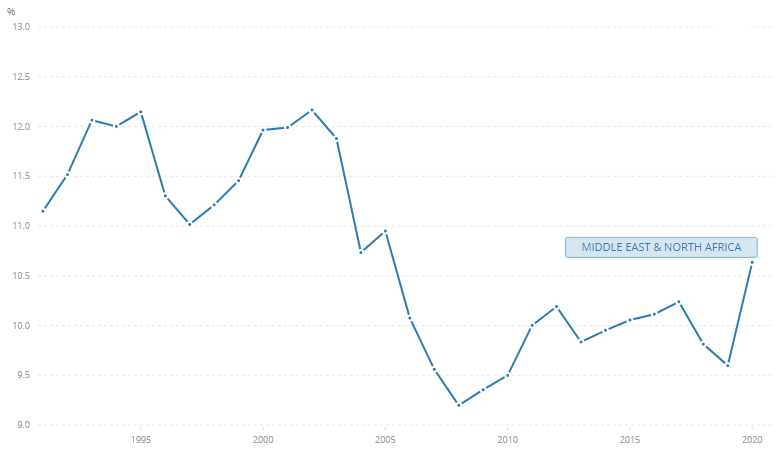

Figure 1: Unemployment rate (percentage of the total labour force), Middle East and North Africa

Source: International Labour Organization, ILOSTAT database. December 2021.

The unemployment rate (percentage of the total labour force) in the region is estimated as 10.5% in 2021. We note a significant decrease from 2003 when the figure was above 12% (see Figure 1).

The effects of entrepreneurship on economic development depend on the quality and type practised in a country, where only high-expectation entrepreneurs who identify and exploit high-growth opportunities contribute to the economic growth of nations (Maliki and Benghalem, 2019).

MENA countries have launched a wide range of employment and entrepreneurship initiatives to absorb youth unemployment and increase the region’s global competitiveness. For example, between 2007 and 2014, Egypt alone implemented over 180 projects related to youth employment (Eichhorst and Rinne, 2015).

The NGO (non-governmental organisations) sector has been heavily involved in these programmes. For example, INJAZ Al-Arab, founded in 2004, has provided youth workforce readiness and entrepreneurship training throughout the Arab world, expanding to 14 countries by 2018. In 2008, it introduced the Sila-tech Foundation to link Arab youth to the jobs and resources needed to create their own businesses.

In Algeria, a new ministry responsible for micro-enterprises, start-ups and the knowledge economy was created in February 2020. One of the most significant results was the National Youth Employment Support Agency (ANSEJ), renamed the National Agency for Support and Development of Entrepreneurship (ANADE) to be refocused on an entrepreneurial economic approach.

In Tunisia, college students were allowed to graduate with a business plan instead of a standard curriculum, where they were more likely to become self-employed. But an evaluation of youth employment programming in the region showed that the majority centred only on technical skills training, followed by training in soft skills. Combined entrepreneurship training, employment services and other youth employment programming composed less than 10% of the inventory programmes (Angel-Urdinola et al, 2010). These strategies raise entrepreneurship and innovation, purported to be critical drivers of economic development.

To address ambiguities about the impact of entrepreneurship on MENA countries’ economic growth, our recent research focuses on nine: Algeria, Bahrain, Jordan, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates (Benghalem et al, 2022). The period analysed is between 2006 and 2018, based on the metrics needed for the research, especially entrepreneurship variables.

In addition, our study employs four control variables: human capital; the money supply; governance quality; and foreign direct investment. Our empirical analysis offers insights on the feedback effects between entrepreneurship, economic development and the other control variables in the MENA region.

Our findings suggest that the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic development varies with the category of entrepreneurs; the self-employment rate negatively affects GDP per capita while the level of new business creation has the opposite effect.

These findings lead us to conclude that traditional self-employed individuals do not support economic growth in the MENA region. This type of entrepreneurship is an escape plan out of unemployment and poverty, especially in economies where social institutions are fragile and impractical.

Furthermore, we find that this type of entrepreneurship (self-employment) does not attract high human capital quality; we find an inverse relationship between educated people and the self-employment rate.

But there is a positive relationship between healthy educated people and the number of new people starting legal businesses. These findings suggest that healthy, educated people prefer to pursue careers where entrepreneurship regularly forms a legal entity, a corporation, an LLC (limited liability company) or a partnership.

Another factor where the effect is not uniform towards the types of entrepreneurship is the total stock of money circulating in the economy. It adversely affects the self-employment rate and positively affects new businesses. This phenomenon is familiar in economies with high inflation and low interest rates.

To assess entrepreneurship and adopt the right policies, MENA countries will have to provide a more comprehensive ecosystem for entrepreneurial activity.

Further reading

Angel-Urdinola, DF, A Semlali and S Brodmann (2010) ‘Non-Public Provision of Active Labor Market Programs in Arab-Mediterranean Countries: An Inventory of Youth Programs’, World Bank Social Protection Discussion Paper No. 1005.

Benghalem A, SB Maliki, M Kertous and N Hilmi (2022, forthcoming) ‘Assessing the Relationship between Entrepreneurship and Economic Development in the MENA Region: An Empirical Investigation’, World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 18(5).

Cobham, D, and A Zouache (2021) ‘The Arab Spring, and after: Economic features and policy challenges’, in The Routledge Handbook on the Middle East Economy, Routledge.

Eichhorst, W, and U Rinne (2015) ‘An Assessment of the Youth Employment Inventory and Implications for Germany’s Development Policy‘, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA) Research Reports No. 67

Fardoust, S (2016) ‘Economic integration in the Middle East: prospects for development and stability’, Middle East Institute.

Ismail, A, T Schott, M Herrington, P Kew and I de la vega (2017) ‘Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Founding and Sponsoring’, in Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (Issue MENA Region Report).

Kabbani, N (2019) ‘Youth Employment in the Middle East and North Africa: Revisiting and Reframing the Challenge‘, Brookings Institution (Issue February).

Kasseeah, H (2016) ‘Investigating the impact of entrepreneurship on economic development: a regional analysis’, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 23(3): 896-916.

Maliki, S, and A Benghalem (2019) ‘Feedback effects of Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Economic Development: Empirical evidence from selected MENA Countries’. Dpublication.Com.