In a nutshell

Peace agreements and power sharing are just one step towards stability and democracy: even before Sudan’s coup, it was clear that the Juba Agreement was no panacea and that several risks remained.

Achieving permanent stability and democratic transition in Sudan requires JAPS partners not only to respect the agreement and implement its entitlements, but also to adopt additional arrangements outside the framework of the agreement.

Initiatives to augment the JAPS should include a national peace conference, a definitive date for the end of the transitional period, preparation for elections, a ‘national fund for peace’ and a transparent national settlement with broad popular support.

The signing of the Juba Agreement for Power Sharing in Sudan (JAPS) on 3 October 2020 raised hopes of ending almost two decades of internal armed conflict in three of Sudan’s regions. Among 13 armed movements and other opposition groups, Minni Minawi’s Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) in Darfur; and, Malik Agar’s Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), with field presence in South Kordofan and the Blue Nile regions, signed up to the peace process.

One year later, the coup led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan has thrown doubt on whether the peace process can still succeed. In a study published just before the coup, we investigate the prospects of peace and democracy for Sudan as a consequence of the power-sharing provision in the JAPS (Bormann and Elbadawi, 2021).Our analysis produces three main insights:

- First, the power-sharing provisions outlined in the JAPS promised to increase the prospects of peace and democracy within Sudan.

- Second, several threats to the JAPS’ success remained, and one has become reality in the last weeks.

- Third, even without the military coup, the JAPS alone would have been insufficient to bring peace and democracy to Sudan.

The first conclusion of our analysis builds on two decades of research into conflict resolution. In general, scholars found that power sharing between the government and armed opposition groups, such as the movements referred to above, contribute to longer peace spells after an intra-state war officially ends. These findings replicate across multiple datasets, correlational and causal research designs, as well as formal power-sharing agreements and informal power-sharing arrangements.

The body of research distinguishes between three major forms of power sharing:

- Inclusive power sharing between political leaders in central government institutions.

- Territorial power sharing between the central government and autonomous regions.

- Military power sharing in the form of integration of the rank and file of rebel movements into the army.

Our analysis shows that power sharing within the central government and between the central government and Sudan’s regions as outlined in the JAPS promised to increase the country’s chances of peace and democracy. We use several models to simulate the risk of conflict recurrence for Sudan, and find that both the quantity of power-sharing provisions and especially power sharing of the inclusive type decrease the risk that armed conflict between any of the signatories of the JAPS will recur.

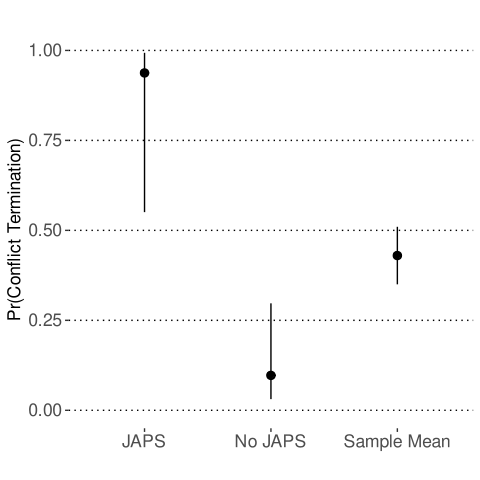

Figures 1 and 2 show simulations for Sudan based on two such models. Figure 1 shows a high chance of conflict termination for Sudan. Based on a comparison of post-conflict peace agreements with and without power-sharing provisions, the inclusive and territorial elements of power sharing in the JAPS mirror previously successful peace agreements in other countries (Johnson, 2020).

Figure 1: Predicted probability of conflict termination for Sudan based on Johnson (2020)

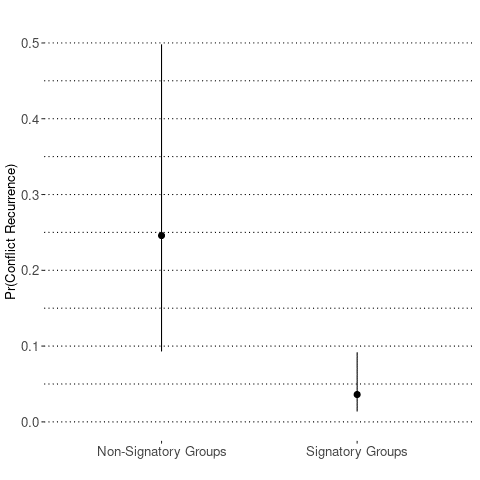

Figure 2: Predicted probability of conflict recurrence for Sudanese ethnic groups based on Cederman et al (2015)

Figure 2 shows a decrease in the risk of conflict recurrence for those ethnically based rebel movements that signed the JAPS compared with non-signatory groups that previously fought the government, such as Abdelaziz Alhilu’s faction of the SPLM-N and Abdelwahid Nur’s SLM.

The analysis is based on a global comparison of de facto inclusion into the government of ethnically based rebel movements (Cederman et al, 2015). These and other empirical models suggest positive effects of the JAPS not only for peace and stability but also for the emergence of democracy (for example, Bormann, 2017, Hartzell and Hoddie, 2020).

But our second conclusion suggests that the JAPS is no panacea and that several risks remain. The models on which we base our predictions depend on a number of different assumptions that need to be met. One crucial condition is the actual implementation of the JAPS, which is questionable after the coup of October 2021.

Another assumption underlying these models is that rebel movements are in fact unitary. Yet the SPLM-N has splintered into two factions, only one of which signed the JAPS. Such rebel group fragmentation endangers the peace process (Cunningham, 2013).

Moreover, the JAPS only addresses those groups that previously fought the government and possibly even signals to other political movements and minority groups that violence is rewarded with government positions and/or regional autonomy.

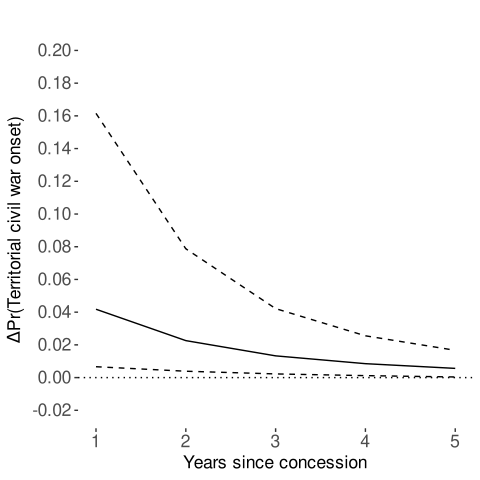

Figure 3 displays the risk of conflict onset for a representative tribe from the latter after witnessing the power-sharing concessions to armed movements with links to other ethnic groups. Compared with a world in which no concessions were extended to any particular ethnic group, the likelihood of rebellion by this tribe increases by 4% in year 1 after the concession, by 2% in year 2, 1.3% in year 3, 0.8% in year 4, 0.5% in year 5, according to the model of Bormann and Savun (2018).

Unfortunately, this prediction is already being corroborated by recent developments in the Red Sea region of eastern Sudan, where the Beja tribal community mounted an aggressive civil disobedience campaign blocking access to Sudan’s main port in response to what they claim to be their marginalisation by the JAPS.

Figure 3: Change in predicted probability of conflict onset for an hitherto peace ethnic group after witnessing concessions to the other ethnic groups in Darfur

Therefore, the most effective deal for Sudan would be one that gives representation to all its citizens and includes civil society. But the coup led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan undermines such a grand bargain.

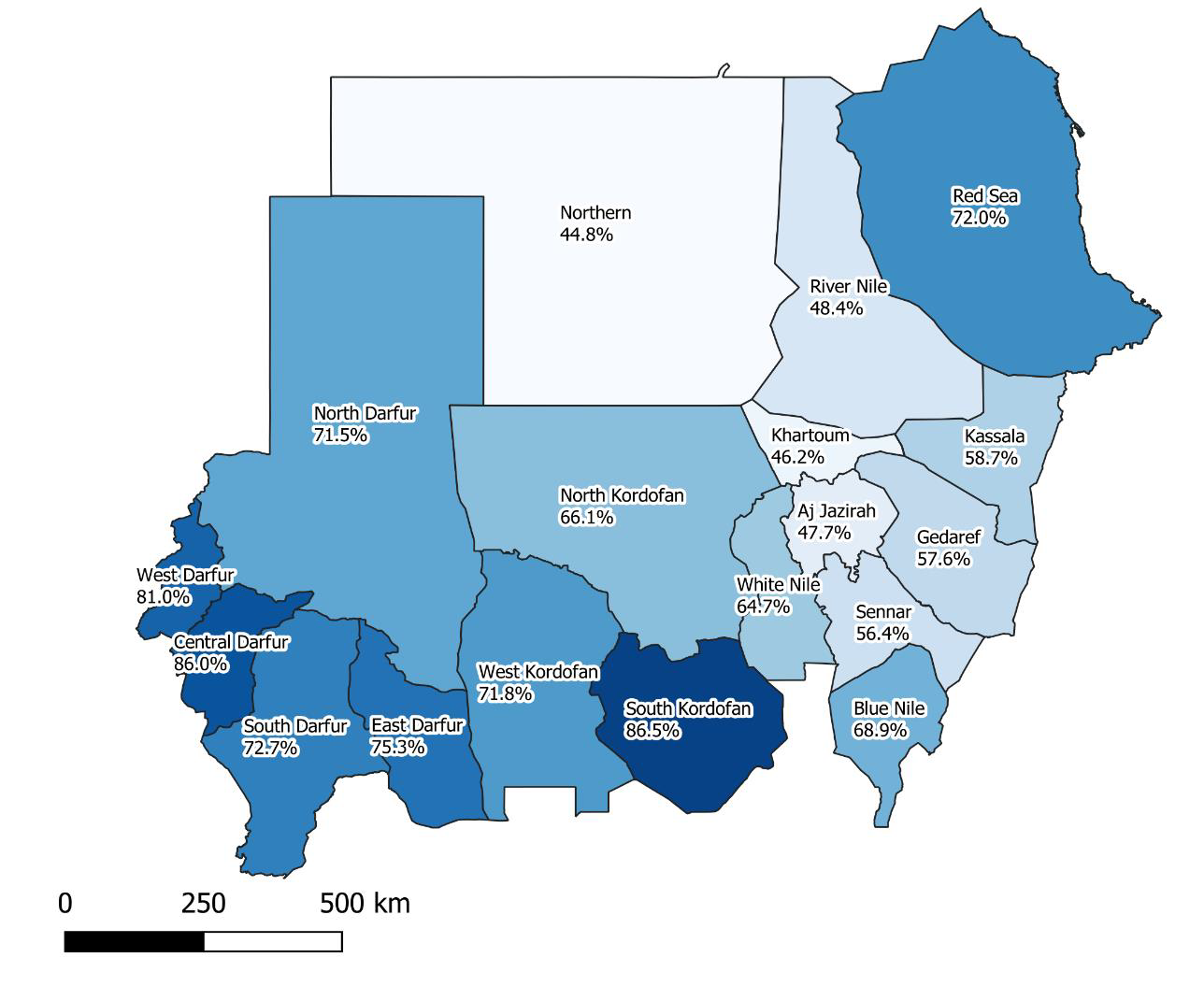

Third, as would be expected the depth of poverty in Sudan is inextricably linked to conflicts. Although the people suffer from massive poverty and low human development standards, the crisis has been particularly acute in the conflict-affected regions of the country (Figure 4). But with most bilateral and multilateral partners of Sudan taking steps to freeze their support in response to the coup, financing many of the promises outlined in the JAPS and demands raised by different political actors will be almost impossible to meet.

Figure 4: Poverty headcount ratio by state, 2014/15 (in percent)

Source: Sudan Poverty Reduction Strategy, March 2021 (World Bank staff calculations based on 2009 NHBS and 2014/15 NHBPS).

Our final conclusion underlines that peace agreements and power sharing are just one step towards stability and democracy. Accordingly, and assuming that the coup is eventually reversed in view of the massive popular resistance and the strong international response to it, Sudan’s success in achieving permanent stability and democratic transition requires the transitional period’s partners not only to respect the agreement and implement its entitlements, but also to adopt additional arrangements outside the framework of the agreement so that it can be developed into a comprehensive national project for peace.

In this context, our research proposes five initiatives to augment and legitimate the agreement further:

- First, holding a national peace conference to expand the base of participation in the transitional authority to include regional and ethnic entities that are not represented in the agreement, thus enhancing its legitimacy and acceptance at the national level, as well as to contain the possibility of renewed armed conflicts in the future.

- Second, a definitive and binding date for the end of the transitional period must be determined to avoid exacerbating conflicts between the ruling partners, and thus exposing the legitimacy of the transitional government to further erosion, threatening the democratic transition project as well as the peace agreement.

- Third, serious preparation for elections (resettlement of displaced people and refugees, population census, delineation of electoral districts, legislation and laws, etc.). The political movement should also work on building wide-ranging electoral alliances on the basis of bona fide national programmes, especially between the historical and modern political parties on the one hand, and armed struggle movements on the other.

- Fourth, the establishment of a ‘national fund for peace’ to be managed by a capable and transparent national commission, in which all the social and political components in the regions affected by the conflicts are represented, and it is sufficiently funded from national resources and foreign aid.

- Fifth, the conclusion of a transparent national settlement, with broad popular support, to address the needs of restructuring and reforming the armed forces, security and police, and achieving transitional justice.

Further reading

Bormann, N-C (2017) ‘Ethnic Power-Sharing Coalitions and Democratization’, in A McCulloch and J McGarry (eds) Power-Sharing: Empirical and Normative Challenges, Routledge.

Bormann, N-C, and I Elbadawi (2021) ‘The Juba Power-Sharing Peace Agreement: Will it Promote Peace and Democratic Transition in Sudan?’, ERF Working Paper No. 1490.

Bormann, N-C, and B Savun (2018) ‘Reputation, Concessions, and Territorial Civil War: Do Ethnic Dominoes Fall, or Don’t They?’, Journal of Peace Research 55(5): 671-86.

Cederman, L-E, S Hug, A Schädel and J Wucherpfennig (2015) ‘Territorial Autonomy in the Shadow of Conflict: Too Little, Too Late?’, American Political Science Review 109(2): 354-70.

Cunningham, KG (2013) ‘Actor Fragmentation and Civil War Bargaining: How Internal Divisions Generate Civil Conflict’, American Journal of Political Science 57(3): 659-72.

Hartzell, C, and M Hoddie (2020) Power Sharing and Democracy in Post-Civil War States: The Art of the Possible. Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, C (2020) ‘Power-Sharing, Conflict Resolution, and the Logic of Pre-Emptive Defection’, Journal of Peace Research 58(4): 734-48.