In a nutshell

The consensus that Lebanon’s crisis originated from overborrowings by the government is valid; yet commercial banks, the central bank and rent-seekers all contributed to the debacle too.

Foreign exchange reserves proved useful in managing the crisis, but this is treatment of a syndrome rather than the illness; the illness falls in the dysfunctionality of the entire system.

Unplanned and disorganised default by the government brought the system to the abyss; as a result, ordinary citizens, particularly those on salaries, are left to face their own fate; unless the world community collaborates to rescue the country, things will deteriorate further.

Reserves were instrumental in the stability of the Lebanese economy, as the country relied on them to signal financial strength, resiliency and willingness to correct for internal and external imbalances.

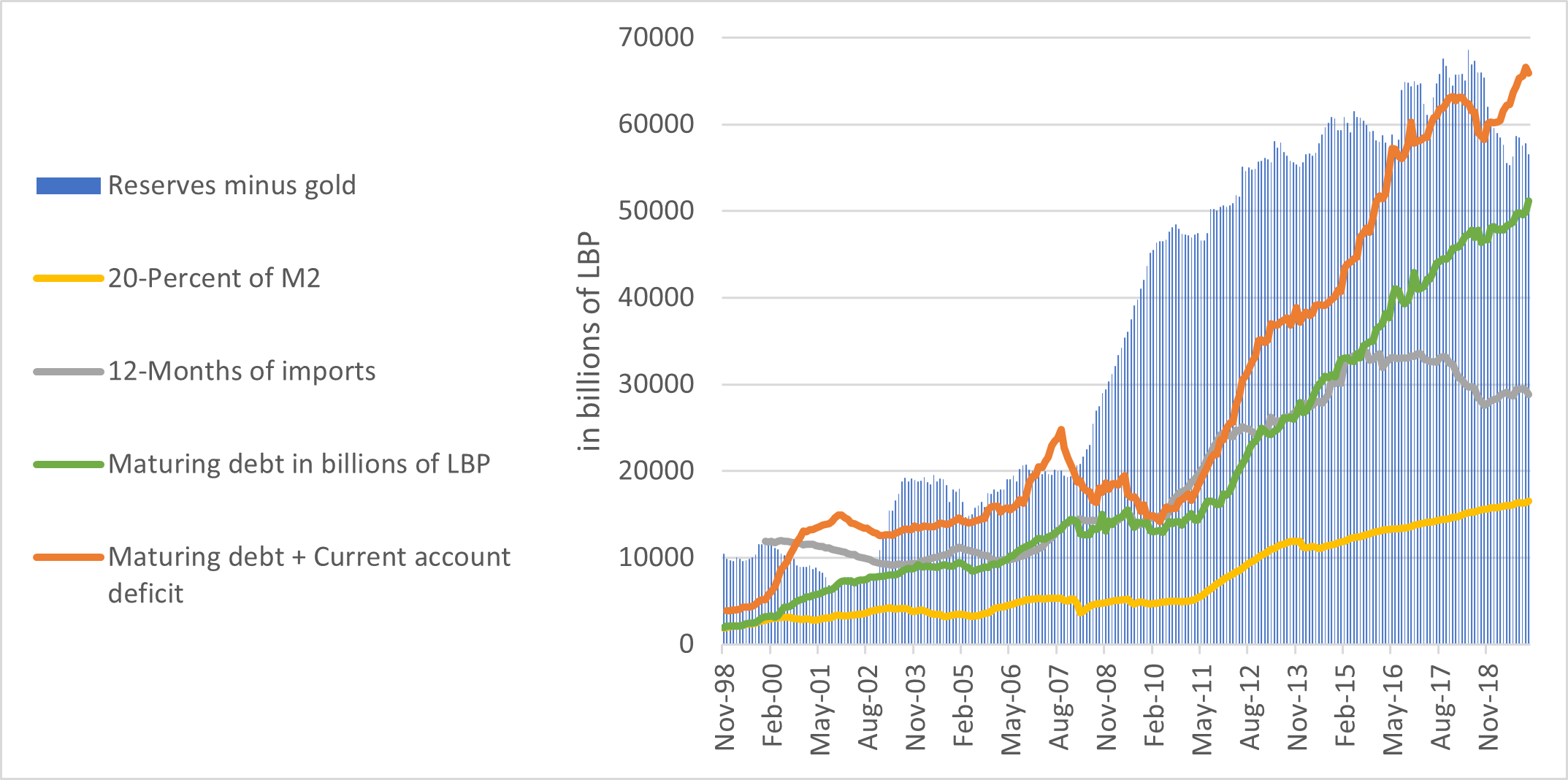

But despite the adequacy of reserves (see Figure 1), holding them incurred a high cost. The opportunity cost of holding reserves in terms of not investing in vital economic sectors or reducing the public debt became unbearable. For a country in which the debt-to-GDP ratio ranks top globally and its debt expenditures top the government expenditures list, the accumulation and holding of a high level of reserves became questionable and a source of concern.

Figure 1: Reserves adequacy metrics

Sources: Central Bank and Ministry of Finance in Lebanon, International Finance Statistics and World Economic Outlook

The debacle

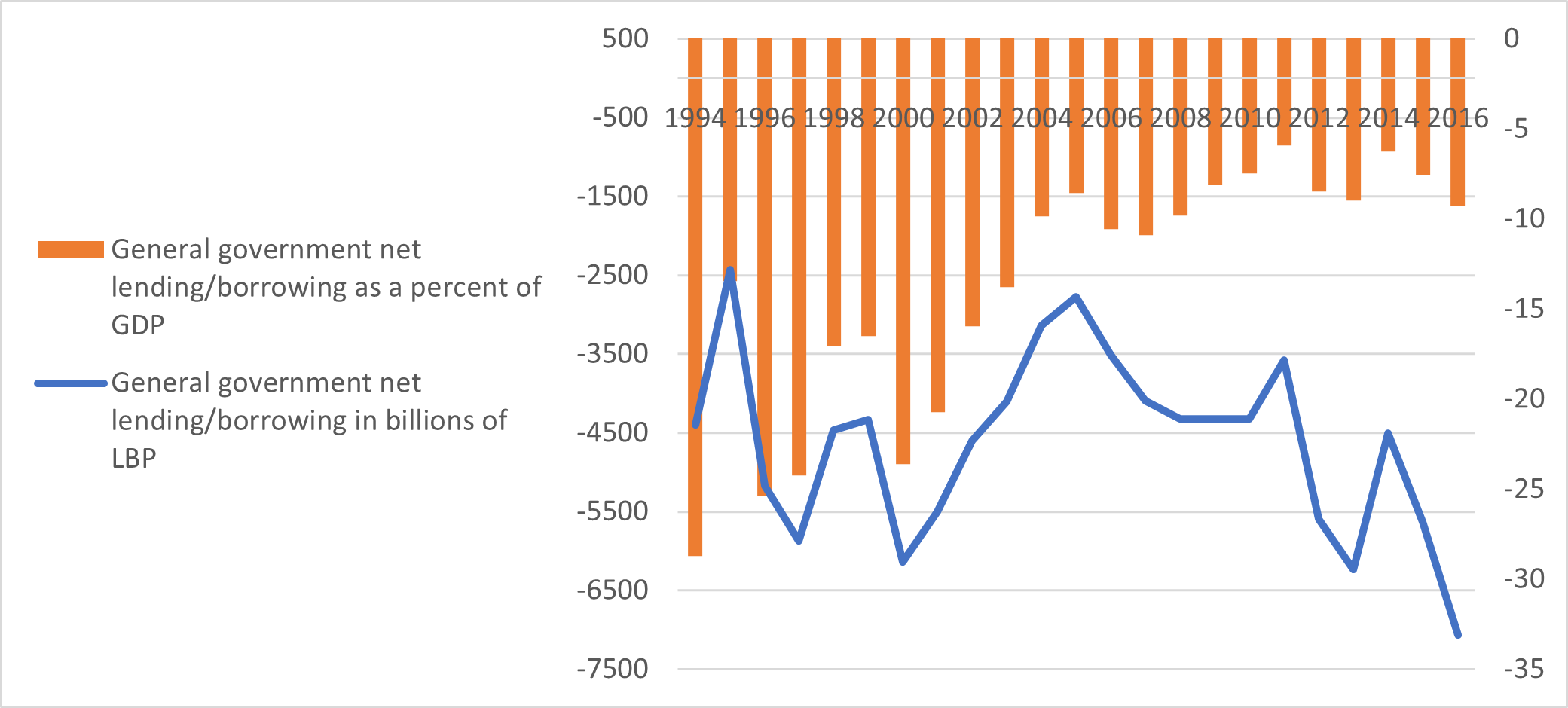

The sudden and ignominious collapse of the economy is attributed to a number of reasons. Among them is the chronic deficit in the government’s overall balance (see Figure 2). The deficit triggered a vicious cycle of borrowing and lending and the rollover of risks and debt restructuring.

The strategy of reducing the short-term maturing debt to long-term was an attempt to delay the inevitable. The strategy reduced the gross financing needs, but it postponed debt payment and services with a much higher cost to a later date. As a result, maturing debts continued rising at an accelerated rate until 2020, when the government failed to meet its debt obligations.

Figure 2: Overall government balance in level and as a percentage of GDP

Sources: Sources: IMF: WEO

In addition, the inclusion of foreign currency debt in total debt was not enough to deter the authority from devaluing the currency. Although devaluation amplified the government’s foreign currency debt, the end result is an improvement in the liability side of the government balance sheet.

The improvement is attributed to the imbalances in the composition of public debt. Foreign currency debt to total debt is approximately 30% of the total. Hence, government debt in local currency is reduced from the equivalent of sixty billion US dollars to less than seven billion.

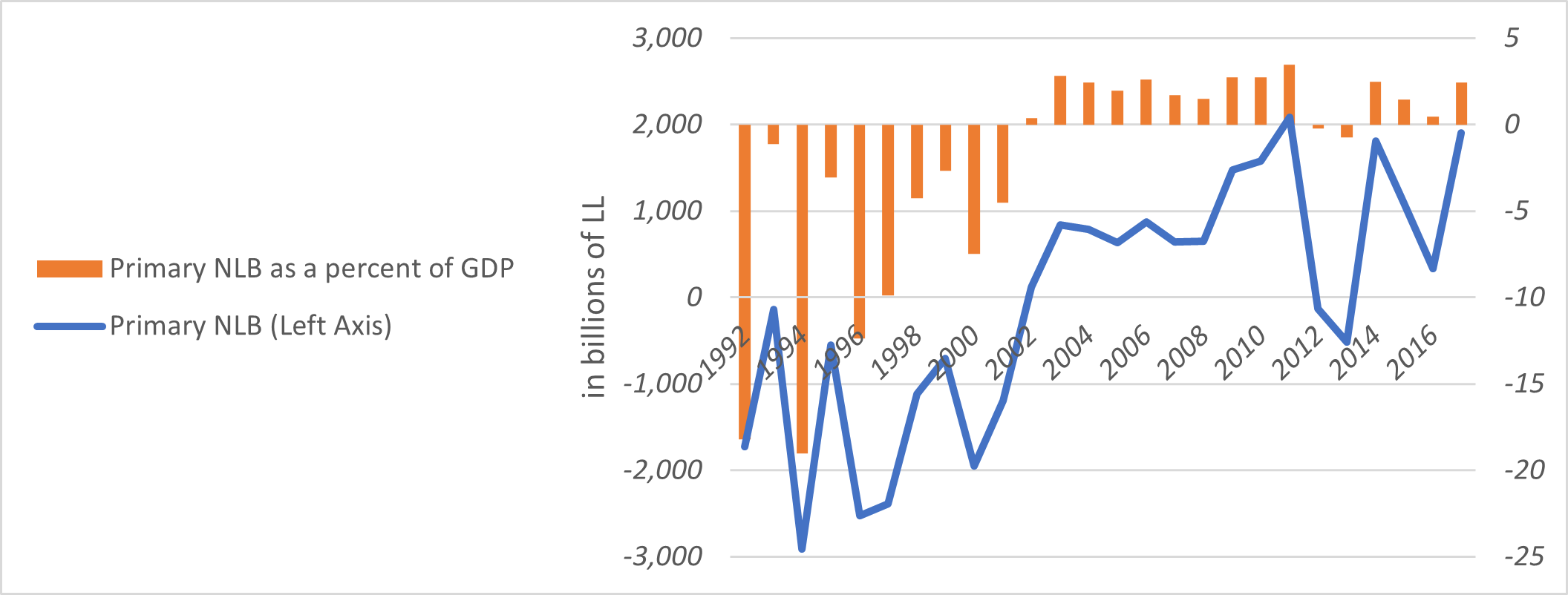

Despite the persistent deficit in the overall balance and the inadequate surpluses in the primary balance (see Figure 3), the government could not take appropriate actions. Instead, its focus was on meeting debt obligations at any cost.

Introducing new taxes, lifting subsidies or reducing wages to alleviate the fiscal deficit is costly politically, socially and economically. Given that the Lebanese government was lagging in the provision of public services, introducing such steps was suicidal. Hence, economic policies were limited to a booming tourism season during the summer, foreign financial assistance, remittances and more borrowings.

Figure 3: Primary net lending and borrowing

Sources: IMF: WEO

The blundering: macro to finance

Defaulting by the government during 2020 triggered the crisis. But as the default was highly expected, the government and the central bank did not coordinate any proactive measures to mitigate the impact of the shock. As a result, depositors lost faith in the banking system and rushed to withdraw their money.

Subsequently, the financial sector and the macroeconomy started to feed on one another and generated a vicious cycle that led to a crisis. Because of the depreciated currency, domestic borrowers who have incurred liabilities denominated in foreign currency found it difficult to repay; thus, there was a massive increase in non-performing loans.

Hence, the system’s ability to extend credit is jeopardised, and along with it, economic activity itself. The result is a deep recession, massive unemployment and social unrest.

Resident and non-resident depositors lured by the high interest rate found themselves in the eye of the storm. Some have liquidated their financial and non-financial assets to secure a good share of the high interest rates. It proved that it was the depositors’ financial and non-financial assets paying for the authority’s misdemeanour.

First, depositors’ money was transferred to the government through two intermediaries: the commercial banks; and the central bank. Then, the government transferred the money back to the commercial banks through the central bank as interest payments on its debt. The cycle of lending and borrowing opened the doors wide to rent-seekers and brought financial engineering into the spotlight. Sadly, the proceeds were transferred abroad.

Decision-makers could have liquidated insolvent institutions and distributed the proceeds to the depositors, or the authority could have nationalised them. Instead, the decision to freeze foreign currency denominated bank accounts and to control capital outflows was catastrophic. The action gave the monetary authority a free hand to finance spending via printing. As a result, the exchange rate and inflation spiralled out of control.

Dollarisation versus reserves and currency depreciation

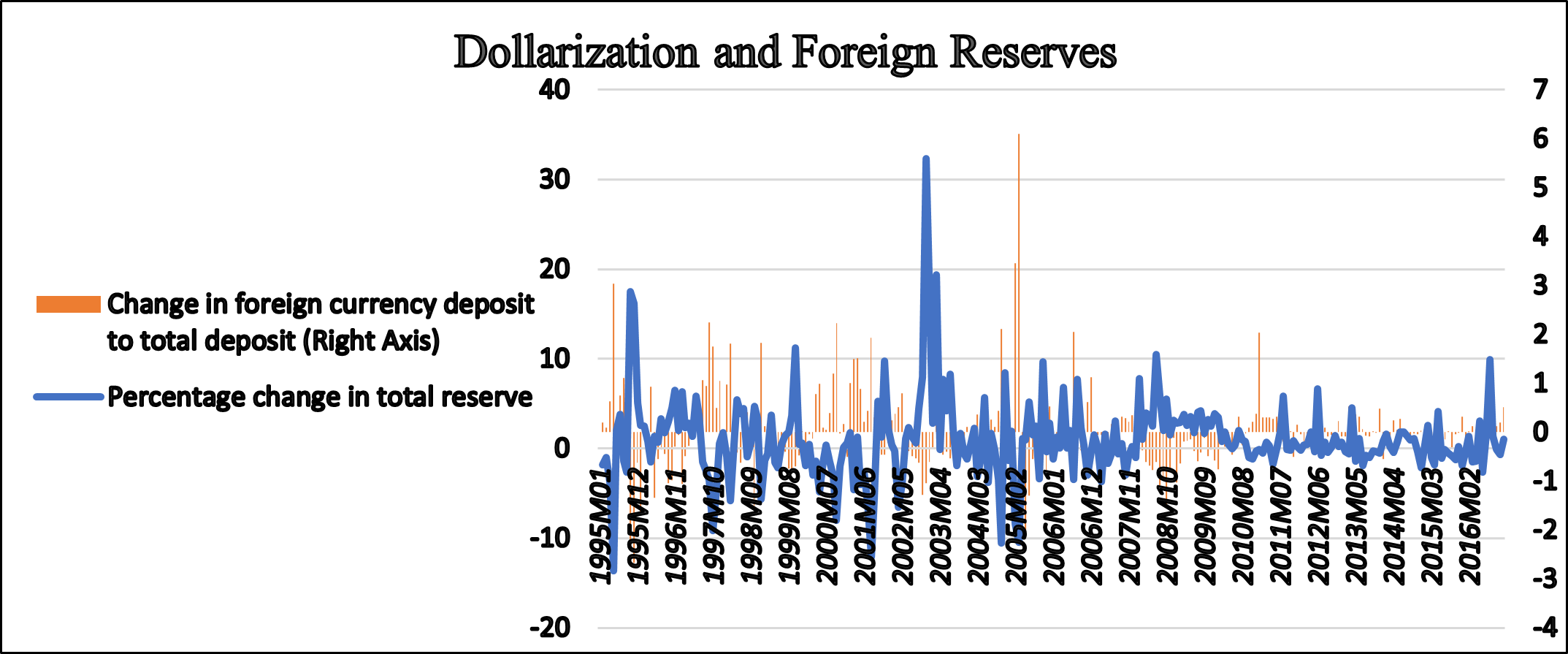

In the past, an adverse political or economic shock triggered an immediate switch from domestic to foreign currencies, generating a high level of dollarisation. High dollarisation for a country operating under a fixed exchange rate regime and free capital mobility translates into the loss of foreign exchange reserves (see Figure 4).

Depositors, who overreacted to bad news, rushed to switch from local to foreign currency denominated bank accounts. The action gave rise to dollarisation and reduced the holding of foreign reserves. Nonetheless, as time progressed, the impact of the adverse shock weakens, and things revert to normal. Depositors’ decisions were based on emotion rather than science.

Recently, aware of the authority’s blunder, well informed depositors rushed to withdraw their money from the banking system. They kept the money either at home or transferred them to foreign bank accounts. Simultaneously, the authority rushed and ordered a bank holiday, followed by freezing foreign currency denominated bank accounts.

Consequently, ordinary citizens are confronted with either depleted local currency denominated bank accounts, frozen foreign currency denominated bank accounts or both. The action brought the entire economic system to a complete halt.

On the other side, the impact of the shock was not symmetric; population segments that rely on remittances are enjoying a very low cost of living, but like the rest of the population, they are still receiving poor government services. On the macro side, the trade deficit-to-GDP ratio registered a 17.5% fall during 2020, the lowest in decades. In addition, the debt-to-GDP ratio dropped to less than 100%.

Nonetheless, the adverse effects of high inflation and depreciation are catastrophic. The population segment that relies on the public sector is hard-hit. Depreciation brought their salaries to less than 10% of what they used to be. Ordinary citizens like school teachers and army officers found themselves in awkward situations and were left alone to face their fate. The debacle put half the Lebanese population below the poverty line.

Figure 4: Dollarisation and foreign reserves

Sources: Central Bank of Lebanon

Conclusion

The mission impossible of blaming one entity and not the others brings a call for reforming the entire economic, judicial and political system. Otherwise, shrewd investors and government advisers will always find ways to manipulate the system to their advantage and the advantages of their employers. Again, vicious cycles will feed on one another, and new tragedies will emerge.

Unless the world community collaborates to rescue the country, the situation will worsen further. The willingness to help Lebanon and its people manifested itself in the aftermath of the August 2020 port explosion. Fellow Arab countries and other friendly ones rushed to rescue the Lebanese people.

Lebanon is very rich in its human capital, beautiful nature and strategic location. With strong political will and accommodating external conditions, the country will recuperate in less than a year.

Further reading

Aizenman, Joshua, and Daniel Riera-Crishton (2008) ‘Real Exchange Rate and International Reserves in the Era of Growing Financial and Trade Integration’, Review of Economics and Statistics.

Kassim M. Dakhlallah (2020) ‘Public Debt and Fiscal Sustainability: The Cyclically Adjusted Balance in the Case of Lebanon’, Middle East Development Journal.

Kassim M. Dakhlallah (2019) ‘Reserve Adequacies and the Determinants of Foreign Exchange Reserves: An Empirical Analysis Through the Vector Error Correction Model’, Review of Middle East Economics and Finance.

Delatte, Anne-Laure, and Julian Fouquo (2012) ‘What Drove the Massive Hoarding of International Reserve in emerging Economies? A Time-Varying Approach’, Review of International Economics.

Jeanne, O, and R Ranciere ( 2011) ‘The Optimal Level of International Reserves for Emerging Market Countries: A New Formula and Some Applications’, Economic Journal.

Obstfeld, Maurice, Jay Shambaugh and Alan Taylor (2010) ‘Financial Stability, The Trilemma, and International Reserves’, American Economic Journal:Macroeconomic.