In a nutshell

New research on the impacts of armed conflict on individual and family lives sheds light on household decisions related to child discipline, labour market decisions, breastfeeding, vaccinations and access to fresh water.

One example of the impact of conflict lies in household health decisions: there is a significant decline in the probability of breastfeeding among children in regions with more intense conflict, and mixed results regarding the duration of breastfeeding.

International organisations can play a role in alleviating these impacts on family health: for example, children in high conflict areas are more likely to have been vaccinated against tuberculosis and measles.

Episodes of armed conflict have a devastating toll on human lives not only through deaths but also physical and emotional injuries. An additional direct impact is the destruction of infrastructure including public amenities, education and healthcare facilities. Other effects include the interruption of government, public and social services.

What is not really obvious is the impact of armed conflict on decisions made by households in affected areas during times of conflict. Such decisions include choices that not only affect the immediate livelihood of household members but also their future prospects such as labour market, education, health and migration.

These choices can have long-term effects on human capital that extend for years, if not decades, beyond the conflict episode. Such consequences extend the armed conflict impact on an affected region far beyond the conflict time period, creating serious downstream outcomes and social costs that are detrimental to economic development. Without accounting for these long-term consequences, one would underestimate the true cost of war.

Research on armed conflict has struggled to document these effects for lack of micro-level conflict and household/individual data. One difficulty is how to measure conflict and whether this measure is at small geographical unit (district, sub-district, city, etc.). What’s more, not all conflicts are created equal, and it is important to distinguish between different types of conflict: ethnic war, civil war, interstate war (across country boundaries), colonial war and violent street protest (see Plümper and Neumayer, 2006).

Using related death records is one measure of the level of conflict intensity (Looney, 2006; Berman et al, 2011); another is the number of attacks on infrastructure and people (Rodriguez and Sanchez, 2012). Recently, Ceylan and Tumen (2021) use satellite images and geographical information systems methods to quantify lost economic activity as a creative way to measure armed conflict intensity.

Another difficulty lies in the availability of household (or individual) level data that can be paired with conflict data. Ideally, such data would provide detailed information about each household member, include location information (preferably at the smallest geographical unit to measure more variation due to conflict exposure), and overtime.

My work with my co-authors (consisting so far of five articles) has taken advantage of recent household level data to contribute to this body of research evidence. Using survey data from Iraq and pairing it with geolocational conflict data that records civilian deaths due to conflict, our recent studies have shed light on household decisions related to child discipline, labour market decisions, breastfeeding, vaccinations and access to fresh water.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, and in particular Iraq, offers a unique opportunity to study the impact of armed conflict on household decisions. While the overall number of armed conflicts has been on a decline since 1945 (Gates et al, 2016), the MENA region has had the deadliest conflicts since 2014, including continuing wars in Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen, which account for more than 65% of total world conflict-related casualties.

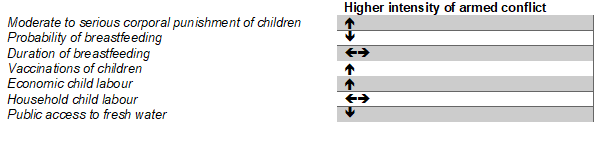

In particular, our empirical work (Malcolm et al, 2019) identifies parenting discipline practices as a direct link between conflict and psychological health of children and adolescent. Children living in conflict-ridden areas are more likely to experience moderate to serious corporal punishment at home.

Our next three studies focus on the health impact of decisions at the household level. In Diwakar et al (2019), we document a significant decline in the probability of breastfeeding (both ever breastfed and current breastfeeding) among children in regions with more intense conflict, and mixed results regarding the duration of breastfeeding.

Such findings bring attention to the role of international organisations in alleviating these impacts. A role that seems to be making a difference in terms of vaccinations (as Naufal et al, 2020, documents) is that children in high conflict areas are more likely to have been vaccinated against tuberculosis and measles.

In terms of labour market implications, Naufal et al (2019) finds that armed conflict is associated with higher probability of economic child labour (referring to work outside the household) but has no impact on household labour (chores related to the dwelling).

Finally, Naufal et al (2021) suggests that higher intensity of armed conflict diminishes public access to fresh water for households further widening income inequality of affected families.

The following table summarises these findings.

The consequences of conflict outlined above take further significance for the MENA region because it is home to the second youngest population in the world after the sub-Saharan African countries. The actual impact of armed conflict will manifest itself for years after the current conflict episodes.

Further reading

Berman, E, JN Shapiro and JH Felter (2011) ‘Can hearts and minds be bought? The economics of counterinsurgency in Iraq’, Journal of Political Economy 119(4): 766-819.

Ceylan, E, and S Tumen (2021) ‘Measuring the Economic Cost of Conflict in Afflicted Arab Countries’, ERF Working Paper No. 1459.

Diwakar, Vidya, Michael Malcolm and George Naufal (2019) ‘The Impact of Violent Conflict on Breastfeeding’, Conflict and Health 13:61: 1-20.

Gates, S, HM Nygard, H Strand and H Urdal (2016) ‘Trends in Armed Conflict, 1946-2014’, Conflict Trends, Peace Research Institute Oslo.

Looney, R (2006) ‘Economic Consequences of Conflict: The Rise of Iraq’s Informal Economy’, Journal of Economic Issues, 40(4): 991-1007.

Malcolm, Michael, Vidya Diwakar and George Naufal (2019) ‘Child Discipline in Times of Conflict’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 1-25.

Naufal, George, Michael Malcolm and Vidya Diwakar (2019) ‘Armed Conflict and Child Labor: Evidence from Iraq’, Middle East Development Journal 11(2): 1-18.

Naufal, George, Michael Malcolm and Vidya Diwakar (2020) ‘Violent Conflict and Vaccinations: Evidence from Iraq’, ERF Working Paper No. 1438.

Naufal, George, Michael Malcolm and Vidya Diwakar (2021) ‘Armed Conflict and Household Source of Water’, ERF Working Paper No. 1460.

Plümper, T, and E Neumayer (2006) ‘The unequal burden of war: The effect of armed conflict on the gender gap in life expectancy’, International Organization 60(3): 723-54.