In a nutshell

Due to Covid-19, wage workers in Morocco and Tunisia have lost jobs, been temporarily laid off, and experienced reduced hours, lower wages and delays in pay.

The impact has been minimal for public sector workers, but substantial in the private sector, especially for informal and irregular workers. Farmers, the self-employed and employers have experienced particularly sharp decreases in their revenues.

Although some workers and families are receiving government support, many are falling through a sparse safety net and experiencing large income decreases. Additional social protection and better targeting will be needed to cushion the impacts of the pandemic.

The pandemic is still devastating countries across the world, with over 100 million confirmed cases and 2.2 million deaths to date globally (Dong et al, 2020). Morocco and Tunisia were somewhat spared by the first wave of Covid-19, which hit in the spring of 2020.

But by the November wave of the Covid-19 Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Monitor Survey, on which we report here, both countries were at or close to the peak of the second wave of their health crises. In fact, daily deaths due to Covid-19 peaked in Morocco around 20 November, while in Tunisia, there were two peaks, the first on 11 November and the second on 21 January.

Even though Morocco and Tunisia were affected fairly mildly in the early stages of the pandemic, their governments adopted very stringent measures early on. Both loosened their restrictions substantially by June 2020, with Tunisia adopting one of the least restrictive stances in the world by that time.

With the start of the second wave in October, new restrictions were re-imposed in Tunisia. It took until December 2020 for broader restrictions to be re-imposed in Morocco. While governments tackled the health threat with a variety of restrictions, they also attempted to provide social protection in response to the economic challenges created both by Covid-19 itself and health policy responses. In both countries, programmes were introduced to support households and firms.

In Tunisia, a number of these programmes were limited to the spring confinement period and were not renewed with the second wave because of limited fiscal space (World Bank, 2020). The stringency of measures applied in the spring contributed to their large negative impact on the economy: a 22% contraction in GDP in the second quarter of 2020 (Dubessy, 2020). They may have also reduced the government’s room to manoeuvre when the second wave hit.

Morocco established a special fund equal to about 3% of GDP to address medical needs as well as business and household impacts of the crisis. The fund was financed by the government and voluntary contributions from public and private entities (International Monetary Fund, 2021).

The impact of Covid-19 on wage workers depends on their type of work and the time frame

Informal wage workers (those without social insurance) and especially those working outside establishments or irregularly were particularly affected by the pandemic. Because of the different timing of the second wave government responses, with Tunisia implementing many further restrictions in October, impacts were much more modest in Morocco than Tunisia.

In Tunisia, public sector and formal private sector workers were the least affected, and primarily by a decrease in hours or delays in wage payments. There were higher rates of layoffs for regular informal workers in establishments, regular informal workers out of establishments, and irregular workers. Decreases in hours and wages along with delays in payment were also common experiences among private sector wage workers.

Farmers struggled to work and harvest their crops

Although wage work is the most common employment status in Morocco and Tunisia, 15% of Moroccan workers and 7% of Tunisian workers were farmers in February 2020, prior to the start of the pandemic. The effects of Covid-19 on farmers in both countries were compounded by a simultaneous drought (Karam and Durisin, 2020), the separate impact of which is hard to disentangle.

Relative to the previous growing season, famers in both countries experienced decreases in the days the family worked on the farm, the days they hired outside workers, the days they worked on other farms, and in the use of seeds and other inputs. Compounded by drought, these decreases in farm inputs led to lower harvests, with a more pronounced effect in Tunisia than Morocco.

Covid-19 created an array of challenges for employers and the self-employed

Self-employment can be a survival strategy in challenging economic times (Naudé 2010, 2008), but the self-employed and employers faced substantial challenges during the pandemic. In Morocco, as of February 2020, 29% of the employed were employers or self-employed. The corresponding figure in Tunisia was 15%. While 41% of this group had no employees and thus were self-employed in Morocco, 34% were so in Tunisia.

Nearly three-quarters of this group in Tunisia and two-thirds in Morocco reported a loss in demand over the 60 days prior to the November interview. Many had shut or reduced the hours of their enterprises. In Morocco, only 34% were open with normal hours and in Tunisia 24%. Tunisian businesses were often operating with reduced hours due to government mandate (40%) while in Morocco fewer hours were due to choice (25%), likely driven by reduced demand. Few had permanently closed (5%), which is a promising sign for future economic recovery, although this may change as the pandemic persists.

In Morocco, relatively few enterprises had applied for or received government assistance. In Tunisia, 17% had applied for or received business loans, 8% cash transfers or unemployment benefits, 7% salary subsidies, and 7% loan payment deferrals. Businesses in Morocco were less likely to state that they needed any assistance, but the most common responses for assistance needed were business loans, reduced or delayed taxes, or subsidised products. Tunisians also thought cash transfers or unemployment benefits were needed frequently (10%).

Covid-19 has led to income losses in the face of a sparse safety net

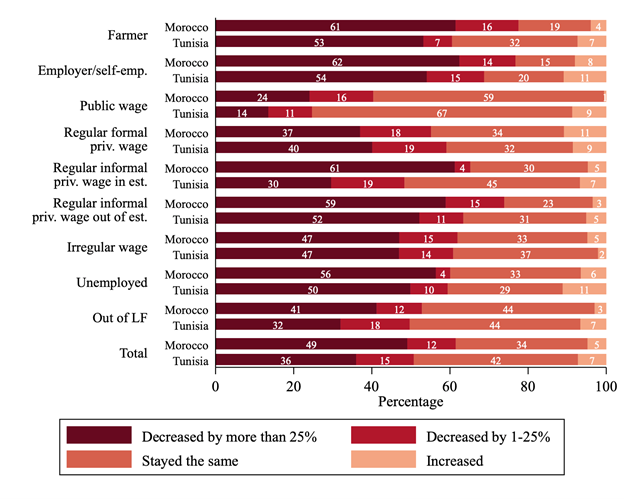

As a result of the economic challenges faced by wage workers, farmers, the self-employed and employers, Moroccan and Tunisian households experienced serious declines in income. Comparing income in October 2020 to February 2020, as shown in Figure 1, 49% of those in Morocco and 36% of those in Tunisia experienced a decrease in income of more than 25%.

Farmers and employers/the self-employed (who together are 44% of the employed in Morocco and 22% in Tunisia) had particularly frequent large decreases in household income. Consistent with layoffs and other patterns, households with informal wage workers experienced frequent steep income declines. Only public sector wage workers had limited changes in income.

Figure 1: Changes in household income from February 2020 to October 2020 (percentages), by country and February 2020 labour market status

Source: Authors’ calculations based on November 2020 Covid-19 MENA Monitor

Existing government social safety nets and new pandemic-specific responses are generally not widespread or well targeted. In Morocco 26% and in Tunisia 18% of respondents had received some form of government assistance. Private formal regular wage workers (42%) were the most likely to receive assistance in Morocco, primarily cash the past month, likely because of the cash transfer programme for laid off workers covered by social insurance.

In Tunisia, regular informal private wage workers outside of establishments were the most likely to be receiving assistance (35%), primarily because they were already in subsidised healthcare programmes. Despite farmers experiencing harsh economic effects from the pandemic, they were less likely to receive assistance than the overall average.

Increasing the reach of the safety net and its financing is a critical task, both to prevent a spiral of income losses that further depresses demand and to prevent deep poverty and its inevitable harms. Targeting the workers who are struggling the most is challenging, because these informal workers are the ones who are not registered in social insurance systems.

Models such as Egypt’s irregular worker programme, giving financial assistance to irregular wage workers during the pandemic, are promising (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD, 2020). But countries also need to think beyond the most vulnerable wage workers to consider designing policies and measures providing support to the self-employed, those running micro-enterprises, and farmers who are facing income losses comparable or worse than those of informal workers.

This column is based on a recent ERF Policy Brief by the same authors (Krafft, Assaad and Marouani, 2021). The results are mostly based on mobile phone survey data from the first wave of the ERF Covid-19 MENA Monitor Survey, which was carried out in November in both Morocco and Tunisia. ERF acknowledges generous funding from the International Labour Organization and the Agence France de Développment for the survey and analysis.

Further reading

Dong, Ensheng, Hongru Du and Lauren Gardner (2020) ‘An Interactive Web-Based Dashboard to Track COVID-19 in Real Time’, The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Dubessy, Frederic (2020) ‘The Covid-19 Crisis Is Undermining the Tunisian Economy and Exacerbating Poverty’, ECONOSTRUM (12 October).

International Monetary Fund (2021) ‘Policy Responses to COVID-19’, Policy Tracker.

Karam, Souhail, and Megan Durisin (2020) ‘North Africa Braces for Smaller Harvests After Another Drought’, Bloomberg (10 March).

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad and Mohamed Ali Marouani (2021) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle Eastern and North African Labor Markets: Vulnerable Workers, Small Entrepreneurs, and Farmers Bear the Brunt of the Pandemic in Morocco and Tunisia’, ERF Policy Brief No. 55.

Naudé, Wim (2008) ‘Entrepreneurship in Economic Development.’ UNU-WIDER Research Paper No. 2008/20.

Naudé, Wim (2010) ‘Promoting Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries: Policy Challenges.’ UNU Policy Brief No. 4.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD (2020) ‘The COVID-19 Crisis in Egypt.’ Tackling Coronavirus (COVID-19): Contributing to a Global Effort.

World Bank (2020) ‘Tunisia Economic Monitor: Rebuilding the Potential of Tunisian Firms: Fall 2020’.