In a nutshell

The Covid-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdown affirmed high-speed internet as a fundamental need and laid down the foundation for managing the internet as a public good.

Broadband is affordable to the average MENA consumer; but long-term sustainability and satisfactory use of internet services are not affordable to low-income groups.

Governments in the region can employ a set of levers to improve broadband affordability, such as smartphone subsidies to marginalised groups or tax breaks on imported devices.

In assessing broadband in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), the following analysis distinguishes between two groups of countries:

- High-income countries (MENA-HIC) with a minimum of US$40,000 GDP per capita, representing 11% of the region’s population. This group includes Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

- Middle-income countries (MENA-MIC) with GDP below US$20,000 per capita. Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia represent this group, which accounts for 35% of the region’s population.

In what follows, FBB signifies fixed broadband and MBB denotes mobile broadband.

Affordability of broadband services

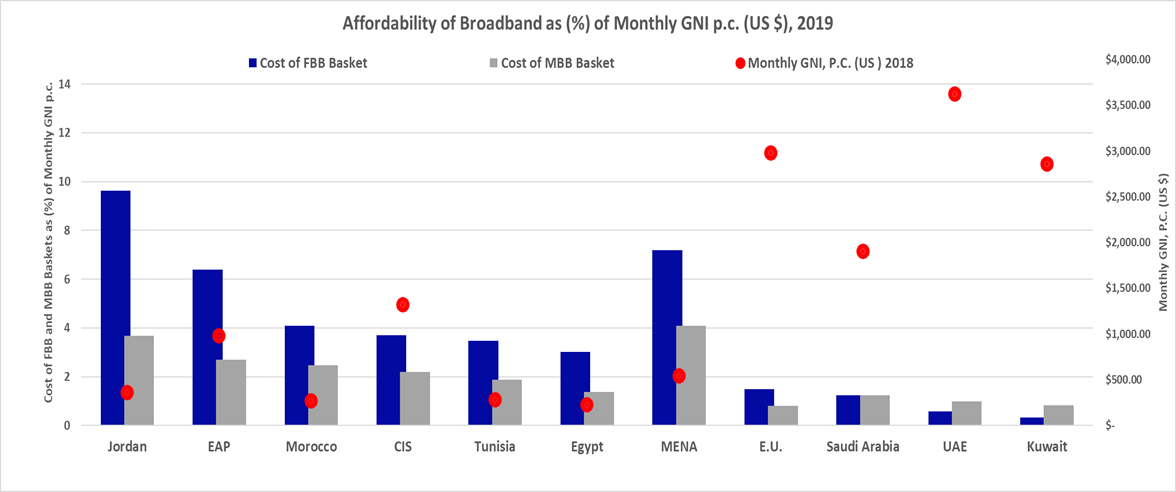

A standard measure of affordability is the cost of an entry-level broadband basket expressed as a percentage of monthly gross national income (GNI) per capita. In 2018, the United Nations Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development announced that entry-level broadband services should be made affordable at 2% or less of monthly GNI per capita by 2025.

The International Telecommunication Union (UN-ITU) has determined a minimum of 5GB monthly usage and a minimum download speed of 256 Kbit/s for an entry-level FBB basket, and 140 minutes, 70 SMSs and 1.5 GB of data plan for an entry-level MBB basket.

Figure 1 shows monthly GNI per capita and the costs of FBB and MBB baskets as a percentage of GNI per capita. Regionally, MENA is well below the world average of 10.3% for FBB costs and comparable to the world average of 4.3% of monthly GNI per capita for MBB costs. At the country level, MENA countries, except for Jordan and Morocco, have recorded cost levels up to 4% and 2% of monthly GNI per capita for FBB and MBB respectively.

Such affordability is a mixed blessing. Consider long-term sustainability especially for low-income groups. Adding an additional GB to MBB plan in Egypt comes at 100% of the original cost. To upgrade from 5GB to the 10GB bracket, subscribers are charged another 87% of the initial cost.

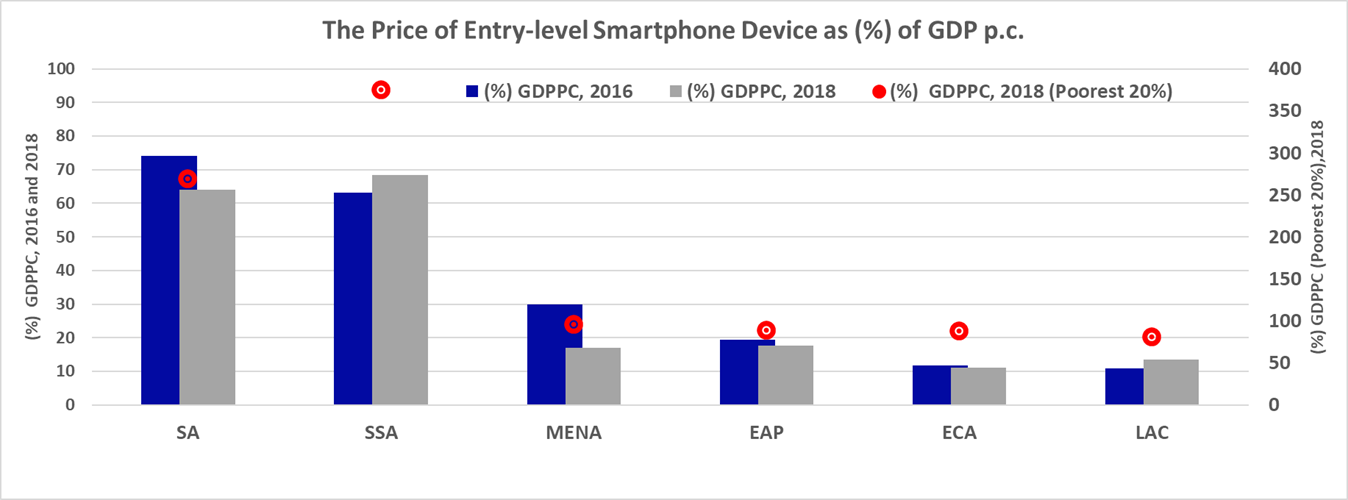

Moreover, affordability measures ignore the cost of an internet-enabled handset (smartphones). Figure 2 shows median prices of entry-level 3G smartphones expressed as a percentage of GDP per capita for the years 2016 and 2018. The fact that the price of an entry-level smartphone represents 96% of GDP per capita for the poorest 20% of the MENA population may explain why smartphone penetration rates in the region are still below 50% of mobile users.

Figure 1: Affordability of broadband as a percentage of GNI per capita, 2019

Source: World Bank and ITU Database. Measuring Digital Development: ICT Price Trends 2019

Figure 2: The price of entry-level smartphone device as a percentage of GDP per capita, 2018

Source: GSMA, The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity, 2019

Access and usage of broadband services

Access and usage of broadband are assessed through:

- Broadband penetration or access rates: measured by the number of subscribers per 100 inhabitants for FBB and ‘active’ MBB services. The active MBB indicator excludes former users who no longer have access to the internet and considers service-paying subscribers who used a network service or made a payable service in the last three months.

- Broadband usage: measured by the percentage of individuals who used the internet via FBB or MBB in the last year.

- Effective use of broadband: measured by the percentage of bank account holders who used FBB or MBB to access their bank account (as a percentage of all bank account holders) in the last three months.

Access

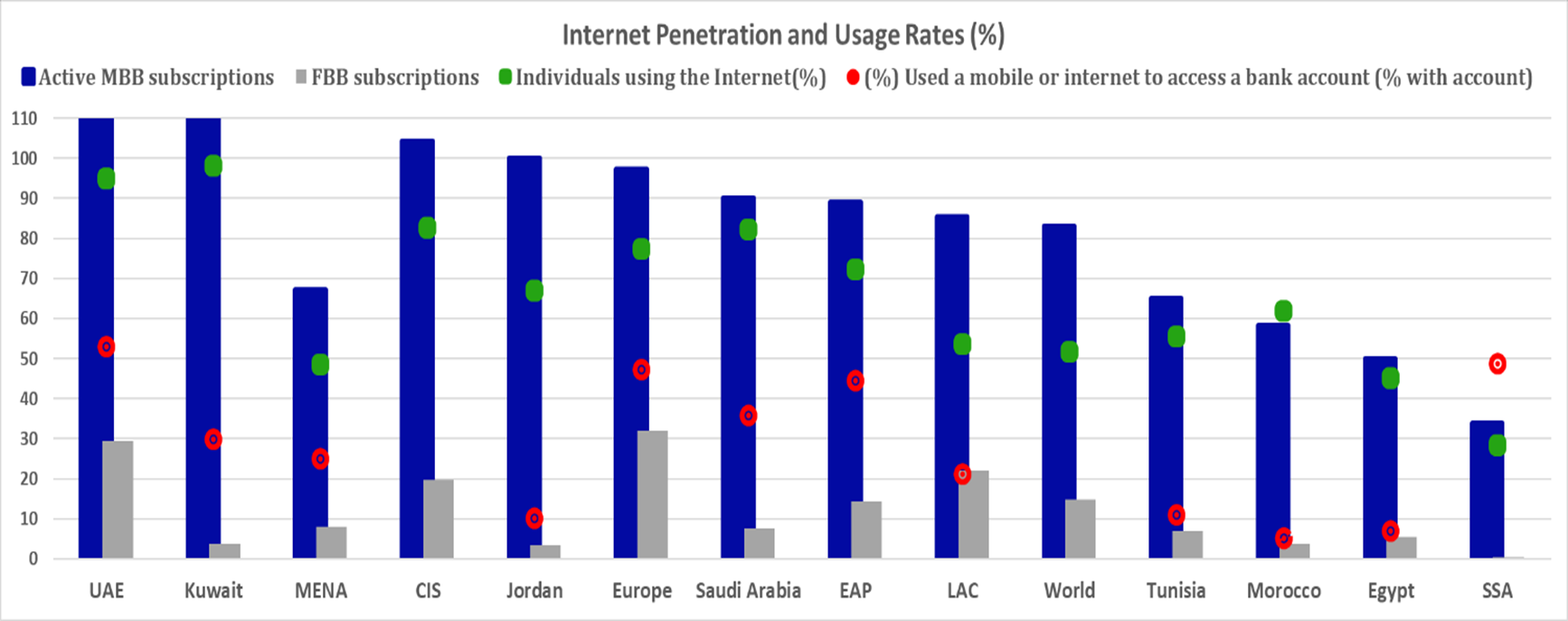

The demand for FBB in the MENA region grew by 68% between 2015 and 2018, yet penetration rates of 8% are just about one-third of rates in Latin America and a half of the world’s average – see Figure 3. The UAE stands out with FBB penetration rates matching those in Europe.

Figure 3: Internet penetration and usage rates, 2019

Source: ITU Statistics (http://www.itu.int/ict/statistics)-various years

Note: Active MBB for UAE and Kuwait is 243 and 127 subscribers per 100 people respectively.

By contrast, active MBB penetration rates stand at 68%, though that is still below the world average of 83%. The UAE and Kuwait are leading the world with record penetration rates, at 243 and 127 subscribers per 100 people respectively. At the other end of the spectrum, Tunisia and Egypt average 50 subscribers per 100 inhabitants. Jordan recorded penetration rates akin to those in advanced economies, an achievement that is credited to a greater degree of market competitiveness in recent years.

These trends should be interpreted with caution. Access rates are not necessarily indicative of consumers’ engagement. A recent study references the term ‘unconscious internet users’, whereby mobile subscribers report using social media and messaging apps on their smartphones but deny access to the internet (Pew Research, 2019).

Usage

Figure 3 shows that less than half of active MBB subscribers had access to the internet, and only 25% of bank account holders managed their accounts online. Certainly, there are wide variations across the MENA region, ranging from 5% in Morocco to 53% in UAE. This is not surprising in a region where less than 50% of adults have bank accounts (Findex Data, 2017).

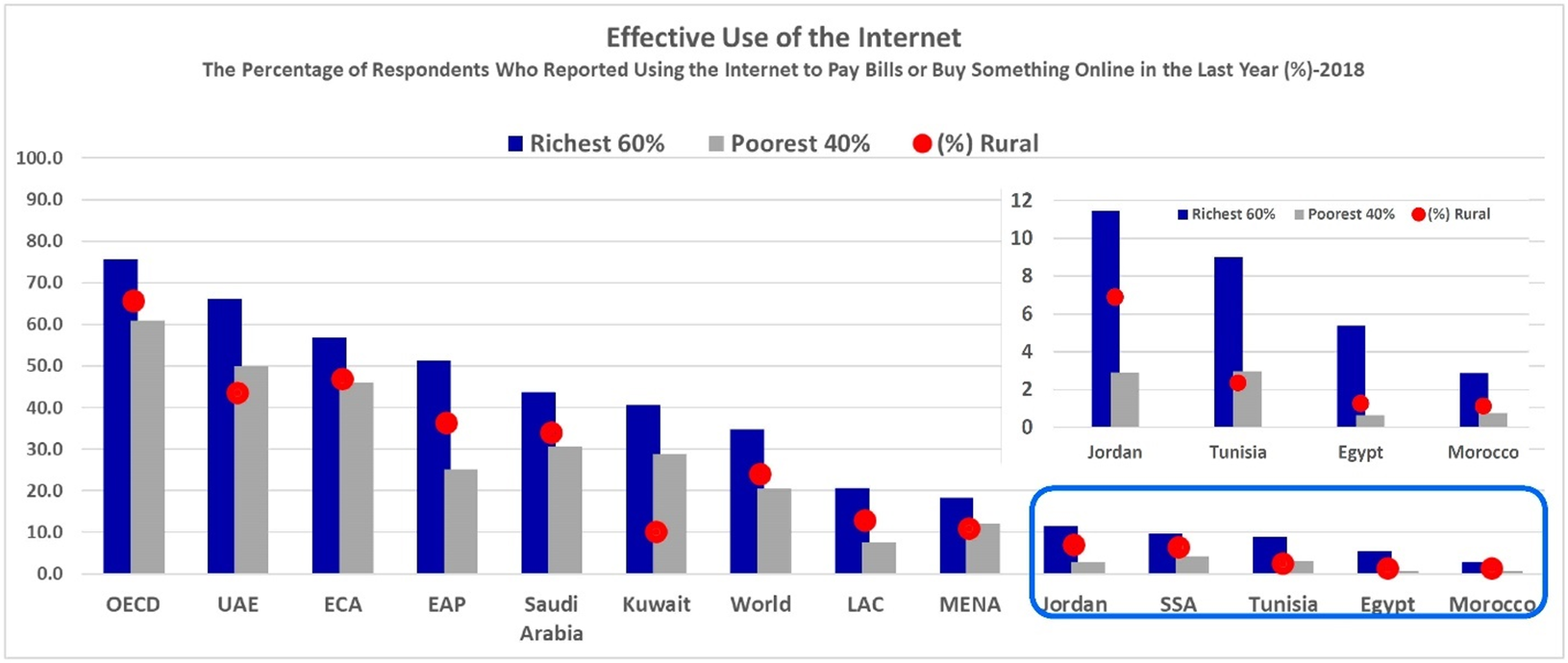

A closer look at the effective use of broadband along income and regional lines is summarised in the percentage of individuals who used the internet to pay bills or buy something in the last year and shown for the richest 60% of the population, the poorest 40% of the population and the percentage living in rural areas.

Figure 4 suggests that the gap between the rich and the poor in online activities is wider across MENA-HIC than it is between MENA-MIC. Digital illiteracy may explain the disparity in the first group.

For the second group of countries, however, the relative similarity between the rich and poor in buying or paying bills online suggests a host of barriers possibly at play such as the unequal distribution of digital infrastructure. In a country with a large population base like Egypt, mobile subscriptions agglomerate in just four out of 27 regions, servicing around 65% of the population (MCIT, 2020).

Figure 4: Effective use of the internet: the percentage of respondents using the internet to pay bills or buy something online in the last year, 2018

Source: Global Financial Inclusion, 2018

The quality of broadband services

Quality is measured by network coverage, speed and bandwidth of broadband services.

Coverage

This is measured by the proportion of the population that lives within the footprint of a network. In 2019, a little over 95% of the MENA population were covered by at least a 3G mobile network. Yet a little over 50% of those living within the footprint of a mobile network lack a smartphone to access the internet (GSMA, 2020).

Speed

A higher broadband speed enables multitasking, bolster productivity and much more. The effects of broadband speed on time savings are significant. For example, it takes about three minutes to download a 5MB file (the average size of a 200-page pdf document) using a network with a download speed of 256 kbits. The same file downloads in 40 seconds with a speed of 1 Mbits and takes four seconds via speed of 10 Mbits.

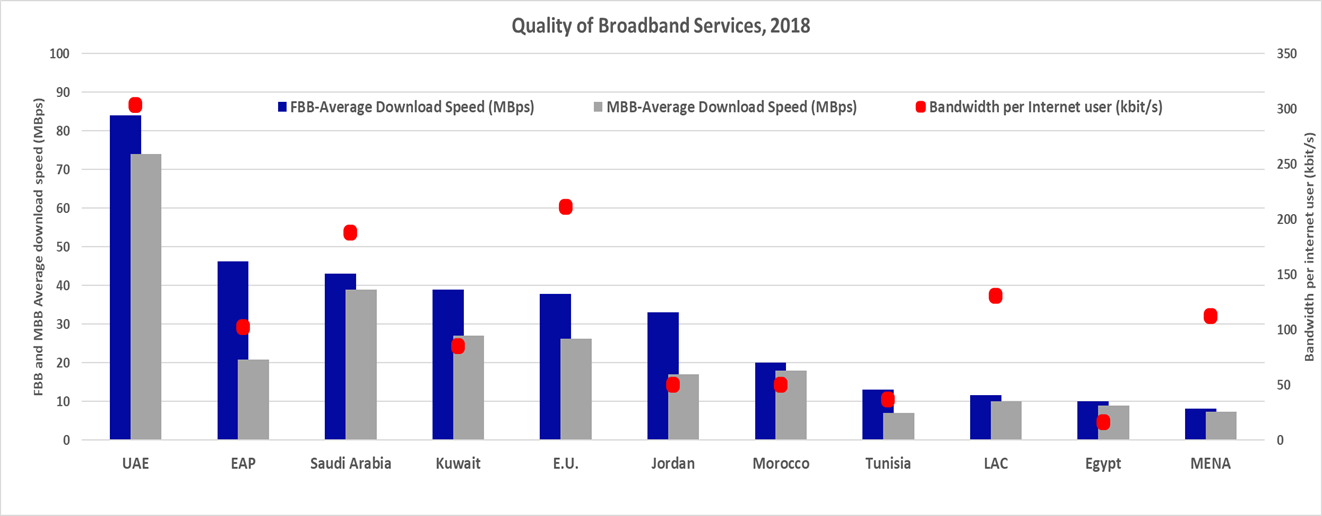

Apart from the UAE, Figure 5 shows that the MENA countries are laggards in broadband speed. The average download speed for FBB and MBB in 2019 stood at 8.1 Mbps and 7.4 Mbps respectively. As a reference, the average download speed for FBB and MBB in the United States are 43 Mbps and 35 Mbps respectively.

Figure 5: The quality of broadband services, 2018

Source: Speedtest Global Index, 2019 (https://www.speedtest.net/global-index#mobile); and Cisco Annual Report, 2019

Bandwidth

This is the maximum amount of data transmitted online in a given amount of time, measured in bits per second (kbps) per user. Since bandwidth capacity depends on a host of factors, there is no pre-determined benchmark to gauge the quality of bandwidth capacity. As a reference, streaming a standard quality movie requires a network with a connection speed of 2 Mbps and 3 Mbps bandwidth in the United States.

Figure 5 shows that compared to other regions, the MENA region performs better on average in bandwidth per user. This average is probably pulled up by the exceptionally high values claimed by UAE. At the other end of the spectrum, bandwidth rates per user in Egypt are as low as 0.25% and 0.43% of comparable rates in the United States and Germany respectively (MCIT, 2020).

Key findings and policy recommendations

Broadband is affordable to the average MENA consumer. But long-term sustainability and satisfactory use of internet services are not affordable to low-income groups. A smartphone unit costs nearly 20% of monthly income, but represents 96% of the average income of the poorest 20%.

3G mobile networks cover 95% of the MENA population. Yet less than 50% of MBB subscribers own or use an internet-enabled phone.

Only 25% of bank account holders manage their finances online.

Buying or paying bills online is carried out by 18% of the richest 60% of the population.

MBB download speed varies between 74 Mbps (UAE) and 7 Mbps (Tunisia), and bandwidth ranges between 300 kbits (UAE) and 16 kbits (Egypt).

FBB download speed varies between 84 Mbps (UAE) and 10 Mbps (Egypt). But the majority are covered by much lower speed: 75% in UAE and Saudi Arabia are within the footprint of 15 Mbps network; and 65% in Egypt are covered by networks ranging in speed between 256 kbits and 2 Mbits

In summary, MENA-HIC affordability, usage and quality matched, and in some instances surpassed, levels recorded in advanced economies. In contrast, MENA-MIC, are trailing behind in all indicators, across all income levels and especially in rural areas.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdown affirmed high-speed internet as a fundamental need and laid down the foundation for managing the internet as a public good.

Committed governments can turn this challenge into an opportunity to catalyse and foster investment in universal access to high-speed broadband, particularly MBB. Universal access ensures a fair distribution of economic gains to all sectors via skill acquisition and knowledge building.

For example, between 2014 and 2016, the percentage of youth/adults who downloaded or configured software in Egypt surged by 4,000%. Using spreadsheets in arithmetic calculations jumped by 620%, and writing computer programs grew by 164%. (UNISCO-UIS-Database). During the same period, internet users grew from 34% to 41%; MBB subscribers expanded from 28% to 44%; and FBB subscribers only increased from 2% to 4%.

Studies in this field agree that a certain threshold of penetration and connection speed is necessary to maximise economic returns to investment in broadband. Likewise, governments in the region can employ a set of levers to improve broadband affordability, such as smartphone subsidies to marginalised groups or tax breaks on imported devices.

Further reading

Pew Research (2019) ‘In some countries, many use the internet without realizing it’.

ITU (2019a, 2019b) ‘The economic contribution of broadband, digitization and ICT regulation: Econometric modelling for the Americas’; and ‘… for the Arab region’.

GSMA (2019 and 2020) ‘Mobile for development: The state of mobile internet connectivity’.

MCIT (2020) Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, Egypt ‘ICT indicators in brief’, February 2020.