In a nutshell

Egypt’s private sector suffers from structural ills that inflate operating costs, constrain productivity and firms’ value-added, and hinder firm growth – these are related to limits on the mobility of human capital; poor access to financing and technology; low opportunities for resource sharing; and limited openness to trade.

Policy should focus on effective promotion of domestic investment in technology and talent, matching talent with high-quality firms; aligning operating conditions in the informal and formal sectors; and deepening the support systems for workers in precarious positions.

Raising firms’ innovation and value-added, streamlining labour mobility, bridging the divide between the informal and formal sectors, and enabling wholesome collaboration and competition among firms will allow the economy to attain more sustainable and inclusive growth.

The Egyptian economy is notorious for its low and stagnating productivity. Evidence suggests that firms face poor access to financing for their expansion and innovation, restrictions on their engagement in trade, low diversification and value-added in their exports, in addition to inflexible relations with their workers (ACET, 2014).

These problems limit firms’ performance as well as their contribution to standards of living in society. This commentary examines business and working conditions across economic sectors, and proposes policy interventions to help level the competitive field and foster sustainable and inclusive growth.

What are the costs and constraints businesses face in Egypt?

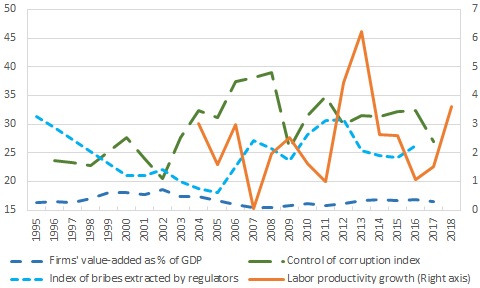

Figure 1 demonstrates that firms’ productivity, as measured by the share of their value-added to GDP, rose slightly during the 1990s, peaking in 2002 at around 18%, and then falling again to reach its lowest level during the global financial crisis of 2007.

Since then, firm productivity has not yet recovered – in 2017, this figure remained less than that during 1991. For comparison, in China, manufacturing firms’ value-added accounted for 29% of GDP, in Algeria 35%, and in Jordan 19%. The level in Egypt has been on par with that of Bangladesh, but the average annual productivity growth rate in Bangladesh has been approximately 13% for many years while Egypt’s has remained under 5%.

The relatively poor productivity and performance of Egyptian firms can be linked to a set of structural problems that inflate firms’ operating costs, constrain factor productivity and firms’ value-added, and hinder firm growth. Egypt has consistently ranked poorly in terms of ease of doing business; in the past year it ranked 120th out of 190 overall, 160th in terms of enforcing contracts, and 171st in terms of ease of trading across borders.

Low-level bribe-demands as well as high-level corruption are rife and an endemic problem. As Figure 1 demonstrates, bribery and corruption in its various forms worsened after 2005, peaking in 2011 and only slightly abating since then. According to the World Bank Enterprise Surveys, in 2004, 49.5% of Egyptian firms reported that corruption was a major or severe obstacle, while in 2007 this figure reached 59.3%, and in 2013 fell slightly to 56.3%.

Figure 1. Selected indicators of business conditions (%)

Notes: Data from Worldwide Governance Indicators; Fraser Institute’s EFW Database; CEIC Data. Index of corruption control, and index of extra payments/bribes/favouritism extracted by regulators are inverted – the lower the better.

Market fragmentation in Egypt’s economy

Egypt’s economy exhibits a highly lopsided and polarised distribution of firm size. Over 90% of firms are micro-sized, and can be characterised as household enterprises. Only a small minority of enterprises are large, even though these enterprises account for half of total employment and the vast majority of domestic investment, output and exports.

These large Egyptian firms often operate with government support and protection, and have limited motive to improve their factor productivity. Only when faced with the entry of informal sector competitors have they been found to respond by increasing their productive efficiency (Ali and Najman, 2016).

Micro and small enterprises (MSEs) operate informally, largely avoiding industry regulations and taxes, and generally unconstrained by labour laws and non-wage outlays. In fact, some firms intentionally restrain their operations and infrastructure in order to remain small and outside the ‘regulatory radar’. At the same time, informal MSEs are practically excluded from public tenders (AbdelLatif and Zaky, 2014) and formal channels of financing (Akhtar and Pearce, 2010) with limited capacity to engage in foreign trade (El-Said et al, 2015).

MSEs have difficulties maturing to larger sizes or breaking even, and face precarious conditions under the shadow of the law. This is due to administrative burdens associated with transition to larger sizes, unreliable access to essential infrastructure including transport networks, electricity and the internet, and firms’ inability to attract qualified labour and capital. MSEs also lack financing from the public and private sectors, and face high financing costs. They are unable to secure the same regulatory treatment as larger firms who often have leverage or lobbying power over policy, or have closer ties to public officials.

In general, the interaction of formal firms with informal firms is limited to the supply chain. MSEs have poor access to – and low capacity to invest in – technology, equipment, talent or market development. They typically provide low value-added upstream inputs and auxiliary services to downstream formal firms, and receive competitive returns on their output.

Competition between MSEs, medium and large firms is thus highly unbalanced. Large formal firms enjoy various protections from foreign as well as domestic competition, are sheltered from low-level bribe-demands, and have the ability to attract high-quality labour and capital. By contrast, informal MSEs avoid taxation and are bound by fewer constraints on their labour relations and operations, but are vulnerable to changing market conditions due to unstable access to financing.

These facts jointly paint a picture of a fragmented economy that is polarised between formal and informal firms, extending across both factor and output markets. Throughout the economy, operating conditions diverge, resulting in some firms, workers and consumers being persistently harmed. This fragmentation is detrimental to aggregate performance because social resources do not flow freely, are not put to their best use, and do not generate network effects.

Ineffective labour markets

One specific manifestation of the poor economic climate and fragmentation of markets is the chronic mismatch between worker skills and employer needs, in addition to persistent unemployment and labour shortages.

On the skills supply side, the illiteracy rate remains high (El-Araby, 2009). More importantly though, public secondary schools do not teach the necessary productive skills, instead emphasising the prospect of admission to universities. At the same time, low returns to university education and high unemployment rate among fresh graduates suggest that employers do not value the skills acquired in tertiary education (Salehi-Isfahani, 2014).

Technical and vocational training programmes are rare and poorly funded (as evidenced by the World Bank Enterprise Surveys). University-corporate collaboration is uncommon and the limited supply of talent is exacerbated by a systematic brain drain through migration. Tech workers and entrepreneurs who are skilled but cannot break into the formal employment sector often migrate in their most productive years.

The public sector is also notorious for crowding out talent from private firms. The public sector has been a significant source of employment – although diminishing in recent years – and students expend substantial resources and time in securing employment in this sector due to better working conditions, non-wage benefits and much higher job security.

But since the public sector has been diminishing in its role as an employer in recent years and compensation has increased to promote civil stability, recent graduates now experience longer waiting times for public-sector employment. As a result, Egypt’s youth unemployment rate has remained at more than two and half times the world average, and the 17th highest in the world (World Bank, 2019).

On the demand side, restrictive employment contract laws and mandated raises reduce labour demand. Formal minimum wages are high relative to typical wages and harmful to employment. Labour unions are also active in their pursuit of collective bargaining at the national level, raising the costs of hiring (Agénor et al 2004). Recent graduates face the prospects of precarious employment in jobs to which they are poorly matched.

There is insufficient transition of workers between informal and formal (and indeed private and public) jobs. Once workers accept an informal job, it is difficult to make the transition to formal jobs, even later in their careers. Informal enterprises act as employers of last resort – a source of sustenance for workers outside the formal market – which does not fare well for labour quality in the informal sector.

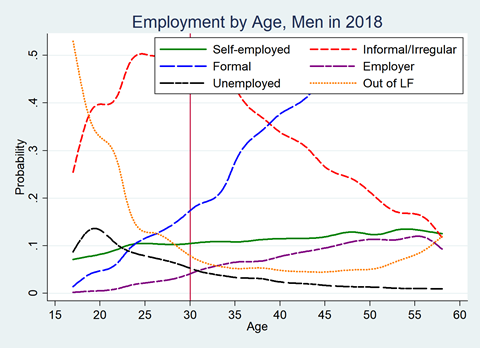

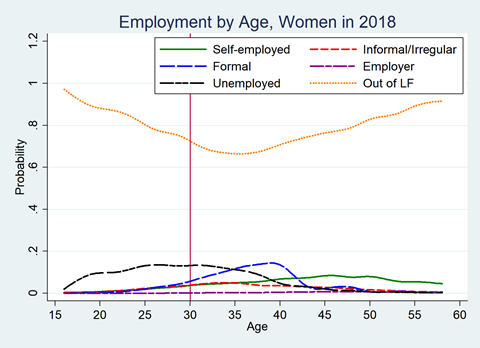

In a recent study (AlAzzawi and Hlasny, 2020) we examine employment outcomes for youth aged 15-29 in Egypt over the last two decades and compare them with those of older workers. Our results confirm relatively bleak prospects for youth.

Figures 2 and 3 show the estimated employment prospects for youth (under 30) and non-youth (30-59) workers. Male youth are predominantly employed in the informal sector or are excluded from the labour force altogether; female youth are more likely to remain out of the labour market throughout their working age years.

Even in their mid-thirties, women’s labour force participation rate increases somewhat, but only in public sector formal jobs. At that age, the probability of being out of the labour force is still three times higher than being employed at all.

These statistics illustrate that Egyptian women only work if they can secure a ‘good’ public sector job (Sayre and Hendy 2013). The particular cultural and social norms (Chamlou et al 2011, 2016; Sidani 2016) in Egyptian society with regard to women’s labour force participation undoubtedly play a role in these findings, but the structural faults in the labour market also exacerbate the imbalances of labour demand and supply in various areas, keeping women out of the labour force, and forcing skilled youth and rural men to migrate for work (Hlasny and AlAzzawi, 2020).

As a result of the skill-job mismatches and structural constraints on labour demand by formal employers, workers tend to concentrate in low-productivity industries. This leads to a low value-added from labour in terms of national output, and a low share of labour wages in GDP (Morsy et al 2014; AfDB 2014).

Figure 2. Employment status prospects of Egyptian men

Notes: Authors’ analysis using 2018 Egyptian Labor Market Panel Survey. Predicted probabilities from multinomial logistic regressions.

Figure 3. Employment status prospects of Egyptian women

Notes: Authors’ analysis using 2018 Egyptian Labor Market Panel Survey. Predicted probabilities from multinomial logistic regressions.

What policies can boost labour productivity?

To understand the performance of the Egyptian economy, one must consider the situation of households as the primary units of economic organisation and production, but also the role of government as an intrusive and rent-seeking economic actor (Bush, 2019).

This commentary has emphasised the generally low level of productivity of firms, the fate of different groups of workers, the vulnerability of informal enterprises, and their interactions with formal firms under the current structural arrangement of markets. The problems of market duality, inequality across different types of units, and gender gaps in Egypt are connected to the prevalence of poor productivity and performance in society.

As such, various policy interventions can be made to effectively match high-quality jobs with talent, align working conditions in the formal and informal labour market, and provide vital support systems for workers trapped in precarious positions (most notably educated youth, rural workers, and women).

Recent deregulatory efforts point in the right long-term direction. In 2017, the Ministry of Investment and International Cooperation introduced a new law attracting foreign investment, providing assurances and designating investment zones, even though this has yet to promote productivity, innovation and growth of domestic firms, especially MSEs.

Policy-makers should extend these efforts by putting more emphasis on knowledge-sharing among domestic firms, and domestic-foreign partnerships. In the longer term, necessary infrastructure investments should be made, and should be offered evenly across different types of firms to promote cooperation, equity, and healthy competition.

Another recent deregulatory effort was the 2018 amendment to the labour and employment law. This amendment contains provisions extending flexibility in firm-worker labour relations and protects formal employers from undue regulations. This can help to integrate the informal sector into the formal one by encouraging the transition of informal employment relations into formal ones, as the original 2003 labour law intended (Wahba and Assaad, 2017).

The amended law promotes worker mobility across public, private formal, and private informal sectors, and promotes level competition among employers. But it remains to be seen how the amended law will perform longer-term.

The government should further support the private sector by reducing tax rates and alleviating administrative procedures in order to level the competitive field between formal and informal firms, encourage firm-size growth and informal-to-formal transitions, and expand the tax base.

To the extent that some workers – particularly marginalised workers such as youth, rural workers and women – struggle to land decent jobs, the government should offer social protections specifically extended to vulnerable and informal sector workers, such as those targeted through cash transfers (OECD, 2018).

Making fiscal policy more counter-cyclical, and supporting vulnerable firms and workers particularly during economic downturns is warranted (Haq and Zaki, 2015). In this regard, extending support for workers’ nutrition, physical and mental health, and vocational training is crucial to maintaining their skills and long-term employability.

The Egyptian economy heavily depends on foreign aid, investment and trade as sources of growth, and much needed capital, but attention should also be directed inward toward improving the incentives given to domestic firms. Fiscal incentives should encourage research and development, and the formation of economic clusters among firms, through grants or tax provisions (AfDB, 2014).

Investment and industrial support policies should be reoriented from energy, construction, real estate and other sectors that bring low value-added to the Egyptian economy to high value-added sectors including technology manufacturing, and professional and business-support services (Haq and Zaki, 2015). Advancing rural growth – through the development of infrastructure, industrial zones, or brownfield projects, or through support for technology in agriculture – should be part of this effort as well (Bush, 2019).

Greater efforts to fight corruption and reduce red tape need to be prioritised since they unduly raise the cost of doing business and reduce returns on investment. In this regard, there are many successful examples of major institutional reforms that were successfully undertaken – in countries such as Hong Kong and Singapore – that could be imitated.

In sum, a variety of policies must be pursued simultaneously, including encouraging innovation and value-added sectors, promoting labour mobility and matching relevant skills with jobs, bridging the informal and formal sectors, and enabling the wholesome collaboration and competition among firms. This will lead to higher growth rates across various parts of the Egyptian economy and will foster a more sustainable and inclusive trajectory of development.

Further readings

AbdelLatif, L, and M Zaky (2014) ‘The Macro-Micro Nexus and Public Procurement Support Policy for SMEs: The Case of Pharmaceuticals in Egypt’, ERF Working Paper No. 818.

Abou-Ali, H, and R Rizk (2015) ‘MSEs informality and productivity: evidence from Egypt’, ERF Working Paper No. 916.

ACET, African Center for Economic Transformation (2014) ‘African transformation report: growth with depth’.

AfDB, African Development Bank (2014) ‘Egypt: employment dynamics and productivity’. Economic brief.

Agénor, P-R, MK Nabli, T Yousef and HT Jensen (2004) ‘Labor market reforms, growth, and unemployment in labor-exporting countries in the Middle East and North Africa’, World Bank social protection working paper 3328.

Akhtar, S, and D Pearce (2010) ‘Microfinance in the Arab World: The Challenge of Financial Inclusion’, MENA Knowledge and Learning, World Bank.

AlAzzawi, S, and V Hlasny (2020) ‘Labor Market Vulnerabilities of MENA Region Youth: Trends and Factors’, UNU-Wider working paper, forthcoming (Previous version available as ERF Working Paper No. 1275.)

Ali, N, and B Najman (2016) ‘Informal competition, firm productivity and policy reforms in Egypt’, ERF Working Paper No. 1025.

Assaad, R (2014) ‘Making sense of Arab labor markets: the enduring legacy of dualism’, IZA Journal of Labor and Development 3(6).

Bush, R (2019) Economic Crisis and the Politics of Reform in Egypt, Routledge.

Chamlou, N, S Muzi and H Ahmed (2011) ‘Understanding the Determinants of Female Labor Force Participation in the Middle East and North Africa Region: The Role of Education and Social Norms in Amman’, Alma Laurea Working Paper 31.

Chamlou, N, S Muzi and H Ahmed (2016) ‘The Determinants of Female Labor Force Participation in the Middle East and North Africa Region: The Role of Education and Social Norms in Amman, Cairo, and Sana’a’, in Nadereh Chamlou (ed.) Women, Work and Welfare in the Middle East and North Africa.

Diwan, I, P Keefer and M Schiffbauer (2015) ‘Pyramid capitalism: political connections, regulation, and firm productivity in Egypt’, World Bank policy research working paper 7354.

El-Araby, A (2009) ‘The Productivity and competitiveness of the Egyptian economy’, Egyptian National Competitiveness Council, Issue 2.

El Mahdi, A (2009) ‘The changing economic environment and the development of micro and small enterprises in Egypt 2006’, in R Assaad (ed.) The Egyptian Labor Market Revisited, American University in Cairo Press.

El-Said, H, M Al-Said and C Zaki (2015) ‘Trade and Access to Finance of SMEs: Is There a Nexus?’, ERF Working Paper No. 903.

Haq, T, and C Zaki (2015) ‘Macroeconomic policy for employment creation in Egypt: Past experience and future prospects’, ILO Employment Policy Department Working Paper 196.

Hlasny, V, and S AlAzzawi (2018) ‘Return migration and socioeconomic mobility in MENA’, UNU-Wider Working Paper 2018/35.

Hosny, A, M Kandil and H Mohtadi (2013) ‘The Egyptian economy post-revolution: sectoral diagnosis of potential strengths and binding constraints’, ERF Working Paper No. 767.

Morsy, H, A Levy and C Sanchez (2014) ‘Growing without changing: a tale of Egypt’s weak productivity growth’, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development working paper 172.

OECD (2018) ‘Deauville Partnership Compact for Economic Governance Stocktaking Report: Egypt’.

Salehi-Isfahani, D (2014) ‘Education and Earnings in the Middle East: A Comparative Study of Returns to Schooling in Egypt, Iran, and Turkey’, ERF Working Paper No. 504.

Sayre, E, and R Hendy (2013) ‘Female labor supply in Egypt, Tunisia and Jordan’, American Economic Association meeting proceedings.

Sidani, YM (2016) ‘Working Women in Arab Countries: A Case for Cautious Optimism’, in ML Connerley and Jiyun Wu (eds) Handbook on Well-Being of Working Women.

Wahba, J, and R Assaad (2017) ‘Flexible Labor Regulations and Informality in Egypt’, Review of Development Economics 21(4): 962-84

World Bank (2019). Unemployment, youth total (% of total labor force ages 15-24). World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Yassine, C (2013) ‘Structural labor market transitions and wage dispersion in Egypt and Jordan’, ERF Working Paper No. 753.