In a nutshell

In responding to Covid-19, authorities should boost spending on health – including producing or acquiring test kits, contact tracing technology, mobilising and paying health workers, adding health infrastructure and preparing for vaccination campaigns.

A combination of bailouts, eased credit conditions and monitoring is needed to support the private sector, including small and medium-sized enterprises.

Cash transfers to vulnerable households, including expatriate workers, would help to protect them and support consumption.

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – face the dual shock of a pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus and a collapse in oil prices.

The virus has affected GCC and other countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. In addition to the loss of lives, the virus’s spread will confront GCC with both a negative supply shock and a negative demand shock.

The negative supply shock comes first from a reduction in labour – directly because workers get sick with Covid-19, the disease caused by the virus, and indirectly due to travel restrictions, quarantine efforts and workers staying at home to take care of children or sick family members.

The negative demand shock is both global and regional. Economic difficulties around the world and the disruption of global value chains will reduce demand for the GCC’s goods and services, most notably oil. Domestic demand will also decline as a result of the abrupt reduction in business activity.

In addition, uncertainty about the spread of the virus and the level of aggregate demand will hurt domestic investment and consumption. Collapsing oil prices further depress demand in the GCC, where oil and gas is the most important sector. Finally, potential financial market volatility could further disrupt aggregate demand.

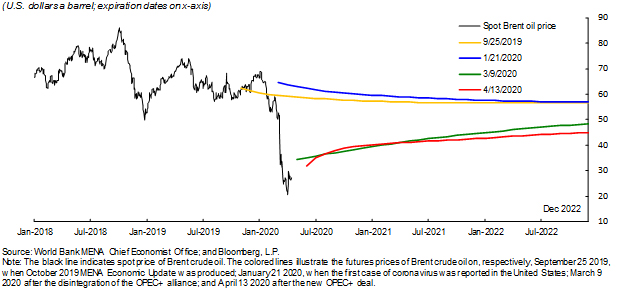

In addition to the shock from Covid-19, the breakdown in negotiations between the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and its allies in the first week of March led to a collapse in oil prices. On 12 April 2020, OPEC+ struck a deal to cut production by 9.7 million barrels a day in May and June. The deal, while sizable, may still be smaller than the shortfall in oil demand (Reuters, 2020).

The futures curve suggests that the market expects oil prices to recover slowly – not reaching $45 per barrel until the end of 2022 (see Figure 1). This would bring a large income decline to the GCC.

Figure 1: Spot and forecasts of the Brent oil price

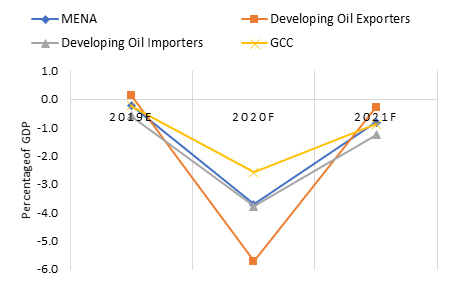

Because of the dual shock, the growth downgrade for the GCC as a whole is 2.6 percentage points in 2020 (Arezki et al, 2020a, b). This can be considered as the cost of the dual shock. In US dollars, this amounts to about $41 billion.

Note, though, that despite the oil price collapse, the growth downgrades for the GCC countries are the smallest among MENA country groups (see Figure 2). This shows the importance of public health systems, which are more advanced in the GCC, and of policy responses.

Figure 2: Costs of the dual shock – growth downgrades (April 2020 versus October 2019)

Source: Arezki et al, 2020a, b

Policy responses in the GCC

GCC countries have put in place unprecedented policy responses, which have helped to soften the effects of the dual shock. The authorities could also consider the following measures.

Tailoring policy responses

To deal with the dual shock, authorities in the GCC should order and tailor their responses to the severity of the shock. They should focus first on responding to the health emergency and the associated risk of economic depression.

Authorities should postpone fiscal consolidation associated with the persistent drop in the oil price and its spillovers until the recovery from the pandemic is well underway. Instead, current emphases should be on budget reallocation and more efficient spending.

In responding to Covid-19, authorities should boost spending on health – including producing or acquiring test kits, contact tracing technology, mobilising and paying health workers, adding health infrastructure and preparing for vaccination campaigns. Scaling up of testing and contact tracing for Covid-19 are especially important to determine the scale of the infection, detect and isolate cases, which will be a factor in deciding whether and how to reopen the economy without causing a second wave of infections.

Supporting the private sector

A combination of bailouts, eased credit conditions and monitoring is needed to support the private sector, including small and medium-sized enterprises. The support, with relevant conditions, will help firms survive the income crunch and prevent mass layoffs.

It is critical to place a priority on strategic sectors – most notably network industries and services, such as transport, logistics, distribution and finance – to protect production capacity and support a future recovery. Governments should focus on elements of business environment regulation, especially out of bankruptcy work out and bankruptcy reforms (see Lyadnova et al, 2019) to resolve corporate difficulties and associated corporate debt restructurings.

The role of sovereign wealth funds, money printing where inflation is low (Gali, 2020) and international borrowing can all be used to support the private sector and soften corporate distress. Bailout measures of strategic firms and sectors could be also considered while ensuring it does not have lasting impact on market contestability.

Supporting vulnerable households, including expatriate workers

Cash transfers to vulnerable households would help to protect them and support consumption. This is relevant for the large expatriate labour force in the GCC countries.

Making expatriate workers eligible for government cash transfers is not only an act of solidarity with those workers but would also enhance the reputation of the GCC as a good place to work. As importantly, supporting the expatriate labour force would speed up economic recovery and prevent further spread of Covid-19 when the workers return to their home countries or when they come back to the GCC for work.

Successful models of quickly deploying technology, including digital, to fight Covid-19 and target assistance should be analysed and replicated. (See Foreign Affairs, 2020, for the experience of East Asian countries.)

Supporting regional and global efforts to contain the crisis

Many MENA countries, including Bahrain and Oman, face large balance of payments and fiscal gaps. Many also carry high sovereign risk premiums. For those countries, additional foreign borrowing on private markets will be difficult. Many other countries in the region will need much international support to help it to navigate an extremely rough patch.

Given the importance of its bilateral aid, the GCC has an important role to play to further the initiative to limit the ballooning of future costs and the risk of failed states entailed by delaying the rapid response to Covid-19. The G20, currently under Saudi Arabia’s presidency, has agreed debt relief to low-income countries to help to free up funds to fight the pandemic (Financial Times, 2020).

Further reading

Arezki, Rabah, Rachel Yuting Fan and Ha Nguyen (2020a) ‘Covid-10 and Oil Price Collapse: Coping with a Dual Shock in the Gulf Cooperation Council’, ERF Policy Brief No. 52.

Arezki, Rabah, Daniel Lederman, Amani Abou Harb, Nelly Youssef Elmallakh, William Louis, Yuting Fan, Asif Mohammed Islam, Ha Nguyen, and Marwane Zouaidi (2020b) Middle East and North Africa Economic Update, April 2020: How Transparency Can Help the Middle East and North Africa, Washington, DC.

Gali, Jordi (2020) ‘Helicopter Money: The Time Is Now’, VoxEU.

Financial Times (2020) ‘G20 agrees debt relief for low income nations’, 15 April .

Foreign Affairs (2020) ‘How Civic Technology Can Help Stop a Pandemic’.

Lyadnova, Polina, Fatema Al-Arayedh, Maha Alali, Lucinda Smart and Mohamed Taha (2019) ‘Bankruptcy and Restructuring in the GCC: An Update on Recent Developments’, Emerging Markets Restructuring Journal 9.

Reuters (2020) ‘Oil prices up 2% after output cut, but demand worries weigh’, 12 April.