In a nutshell

It is possible to keep and extend food subsidies by increasing general VAT.

If there is a preference for not increasing general VAT, it is possible to increase taxation on fuels and lubricants for personal vehicles to finance food subsidies and even decrease VAT.

The Lebanese government should provide access to survey data to researchers, thereby giving policy-makers access to evidence-based policy recommendations that could be produced for free by the academic community

Lebanon is currently facing its biggest fiscal crisis since independence. Public debt now stands at more than 150% of GDP, and the Lebanese government has already defaulted on a Eurobond payment on 9 March.

Among the suggested solutions recommended by analysts, the elimination of certain consumer subsidies and some value-added tax (VAT) exemptions are being considered. At the same time, the government is arguing that it does not want to increase general VAT to ease the burden of the economic crisis on the population.

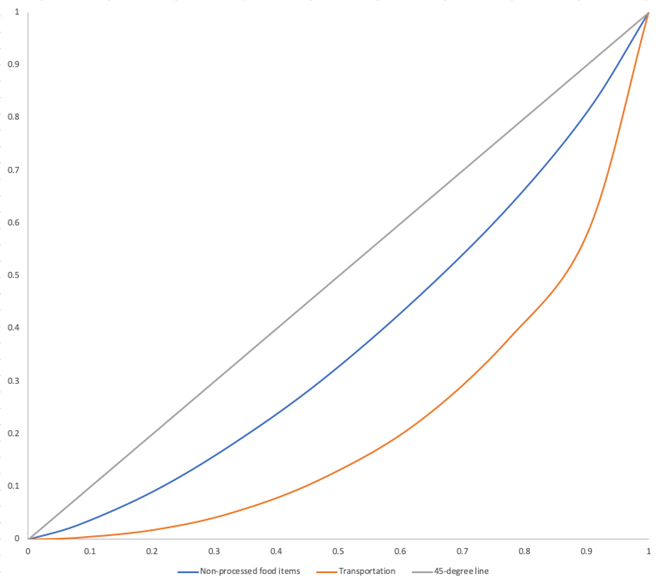

Such economic policy decisions should never be taken without looking at the complete distribution of different categories of expenditures by income categories. To grasp the burden of a consumption tax by types of spending, Figure 1 displays the cumulative distribution of total expenditures of non-processed food items compared with transport cost (fuels and lubricants for personal vehicles).

By looking at the structure of consumption of these two expenditures categories, it is clear that if a consumption tax were to be imposed on food, more of the burden would be experienced by poorer households than imposing a consumption tax on fuels and lubricants for personal vehicles.

Figure 1: Non-processed food versus transport costs.

Source: Makdissi and Seif Edine (2020).

Lebanon subsidises flour, wheat, bread and, indirectly, electricity. There are VAT exemptions for non-processed food and diesel, health, real estate, educational, financial, insurance and banking services, and the leasing of residential property.

Although some VAT exemptions may reasonably be waived, it is surprising that policies that would induce a sharp increase in the price of basic food items are even being considered. Policy-makers usually avoid such policies and typically look for strategies that would mitigate the impact of increasing food prices.

The rationale behind such hesitation can be found in Bellemare (2015). Using monthly data at the international level, that study shows that rapid increases in food prices can explain the emergence of social conflict. This empirical evidence should be taken into account in current policy discussions, since ESCWA (2016) shows that a significant part of the Lebanese population suffers from food insecurity.

Last week, the Lebanese government announced a substantial scaling up of the National Poverty Targeting Program. Although this policy change is certainly a step in the right direction, it covers only a small number of households. According to Bou Khater (2020), this program currently provides benefits to 43,000 of the 150,000 households that applied. The policy change would not compensate for a sharp increase in food prices for the 31% of the Lebanese population who are not always able to afford to eat enough nutritious food.

In a recent study (Makdissi and Seif Edine, 2020), we use information from consumer surveys to identify potential alternatives to the elimination of these subsidies. In our research, the objective is to make as few assumptions as possible about policy-makers’ preferences for redistribution (except assuming a minimal level of inequality aversion). We also adopt a similar approach to the econometric model of demand for these goods.

Our methodology builds on previous research on marginal consumption tax reforms (see Yitzhaki and Slemrod, 1991; Makdissi and Mussard, 2008; and Duclos et al, 2008). Unfortunately, Lebanon is one of the few countries that does not allow access to survey data to researchers. Nevertheless, we have been able to use consumption averages by income categories made available by the Central Administration of Statistics of Lebanon, to explore different channels to reallocate a tax burden by adapting the exiting methodologies to group information.

Our results are striking. The elimination of food subsidies seems to be the worst possible option for policy-makers. We find that it is possible to keep and extend food subsidies by increasing general VAT. We also find that if there is a preference for not increasing general VAT, it is possible to increase taxation on fuels and lubricants for personal vehicles to finance food subsidies and even decrease VAT. Our results are robust to a broad spectrum of econometric assumptions.

The Lebanese government should really consider giving access to survey data to researchers. This would allow policy-makers to rely on evidence-based policy recommendations that could be produced for free by the academic community.

With access to survey data, the results of our research can be extended. For example, using the methodology of Duclos et al (2014), it would be possible to explore ways to increase taxation income in an economically inclusive way by imposing a higher burden on wealthier households.

Further reading

Bellemare, MF (2015) ‘Rising food prices, food price volatility, and social unrest’, American Journal of Agricultural Economics 97: 1-21.

Bou Khater, Lea (2020) ‘Poverty Targeting is not the Solution for Much Needed Social Policy’, Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

Duclos, J-Y, P Makdissi and A Araar (2014) ‘Pro-Poor Tax Reforms, With an Application to Mexico’, International Tax and Public Finance 21: 87-118.

Duclos, J-Y, P Makdissi and Q Wodon (2008) ‘Socially-Improving Tax Reforms’, International Economic Review 49: 1505-37.

ESCWA (2016) Strategic Review of Food and Nutrition Security in Lebanon.

Makdissi, P, and M Seif Edine (2020) ‘Is the elimination of food subsidies the right policy to address Lebanon’s public finance crisis?’, MPRA Paper No. 99070.

Makdissi, P, and S Mussard (2008) ‘Analyzing the Impact of Indirect Tax Reforms on Rank Dependent Social Welfare Functions: A Positional Dominance Approach’, Social Choice and Welfare 30: 385-99.

Yitzhaki, S, and J Slemrod (1991) ‘Welfare Dominance: An Application to Commodity Taxation’, American Economic Review 81: 480-96.