In a nutshell

Recent data on private sector establishments in Egypt show the re-emergence of the ‘missing middle’: employment growth in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) exceeds that in much smaller and much bigger establishments; and SMEs’ contribution to private sector job creation has increased substantially.

This bodes well for the Egyptian economy and labour market as SMEs are more efficient in their use of labour and capital than their smaller and bigger counterparts; they are also more likely to create formal jobs than micro establishments and to employ women and educated workers.

Significant policy reforms introduced in the past 15 years can be credited with the re-emergence of Egypt’s missing middle, but much more needs to be done to improve the business and regulatory environment facing these firms.

According to a recent study conducted under the auspices of the Egyptian Ministry of Planning, Monitoring and Administrative Reform, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are emerging as an important source of job creation in the Egyptian economy (Assaad et al, 2019). (These results are primarily based on analysis of data from three comparable establishment censuses carried out in 1996, 2006 and 2017 in conjunction with the decennial population and housing censuses. Additional data sources include the Economic Census of 2012/13 and official labour force surveys.)

Employment in private establishments made up 33% of employment in the Egyptian economy in 2017. The remainder was made up of employment outside fixed establishments (46%), employment in government (18%) and employment in state-owned enterprises (3%). The share of employment in private establishments increased from 23% in 2000 to 33% in 2017.

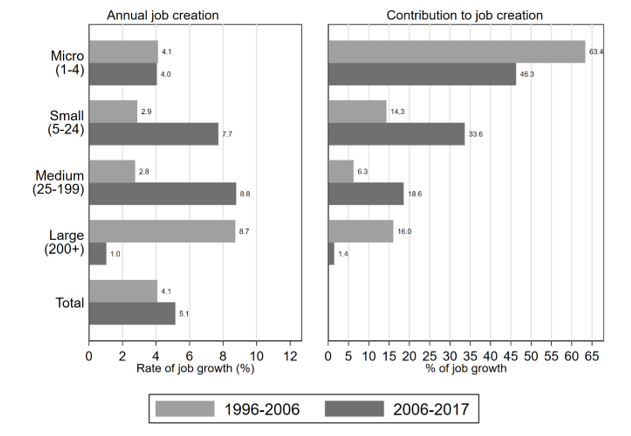

Before 2006, micro enterprises (those with between one and four workers) and large establishments (200-plus employees) largely dominated job creation within the private sector. Micro establishments accounted for 63% of job creation from 1996 to 2006, and large establishments accounted for 16% (Figure 1). The contributions of SMEs were 14% and 6%, respectively.

In contrast, between 2006 and 2017, the contribution of micro establishments to private job creation declined to 46% and that of large establishments shrunk to only 1.5%. Conversely, the contribution of small establishments more than doubled to about 34% and that of medium-sized establishments tripled to about 19%.

These dramatic and unprecedented shifts are due to the acceleration of employment growth in SMEs. Employment growth in small establishments accelerated from 2.9% a year in the period 1996-2006 to nearly 7.7% a year in the period 2006-2017. That of medium-sized establishments went from 2.8% a year to 8.8% a year in the same two periods.

This contrasts with stability in growth rates in micro establishments at about 4% a year and a sharp deceleration of employment growth in large establishments from 8.7% a year to just 1% a year. These shifts could either be the result of net employment changes within the various size categories or due to the reclassification of establishments as micro establishments grow into small establishments, small establishments grow into medium-sized establishments and large establishments shrink into medium-sized establishments.

Figure 1: Annual rate of job creation (percentage) and contribution to job creation (percentage of job creation) by establishment size, 1996-2006 and 2006-2017.

Source: Assaad et al (2019),

The re-emergence of the missing middle is even more pronounced among the top-10 industry groups in terms of contribution to job creation in Egypt from 2006 to 2017. (An industry group is defined as an industry at the three-digit level of the International Standard Industrial Classification, ISIC rev. 4.)

The top-10 industry groups that contributed to job creation in private establishments are mostly in the retail, distribution and service space. They include various retail sub-sectors, such as food and beverage, specialised and non-specialised stores. They also include warehousing and storage, restaurants and food service, personal services, non-governmental organisations, financial services, specialised construction and sawmilling. Together, these top-10 industries contributed 65% of net employment growth in private sector establishments from 2006 to 2017.

Interestingly, the share of SMEs grew faster in these top-10 industries than in private sector establishments overall. While the share of small establishments grew from 19% to 25% overall in 2006-17, it grew from 13% to 22% in these top-10 industry groups. Similarly, while the share of medium-sized establishments grew from 9% to 13% overall, it grew from 3% to 9% among the top-10 contributors.

Thus, although the top-10 industry groups are generally more dominated by micro establishments providing mostly informal jobs, the re-emergence of the missing middle is more pronounced among them than in the private sector overall.

Within small establishments, the top-10 industry groups contributing to job creation look very similar to those for the private sector as whole, but among medium-sized enterprises, the top-10 industry groups include non-governmental organisations, financial services, non-residential social care (such as childcare centres), and warehousing and storage. They also include some manufacturing activities that do not show up at all among the top-10 contributors overall.

Why is the re-emergence of the missing middle a welcome development?

The re-emergence of the missing middle, as indicated by the more rapid growth of SMEs, is a positive development that needs to be encouraged and promoted for a number of reasons.

First, jobs in SMEs tend to have higher labour productivity than jobs in micro enterprises. Indeed, when we examine total factor productivity (TFP) – a measure of productivity that takes into account both capital and labour inputs – jobs in small establishments are the most productive, since they use capital very efficiently compared with medium-sized and large enterprises.

Second, the more rapid growth of SMEs can potentially improve the quality of jobs created in the Egyptian labour market. On average, jobs in SMEs tend to be more formal than in micro establishments. SMEs hire a higher share of educated workers than average and have a higher share of women among their employees than either micro or large establishments. In fact, medium-sized establishments have a higher share of university graduates among their employees than even large establishments.

Thus, the re-emergence of the missing middle has the potential to make the economy more productive, to create better quality jobs that are more suitable to an increasingly educated workforce and to promote women’s economic empowerment.

What policies led to the growth of SMEs and what else can be done to further promote this trend?

In the last 15 years, the promotion of SMEs received increased attention from Egyptian policy-makers. The adoption of the Small Enterprise Law (Law No. 141 of 2004) greatly simplified the rules and procedures for registering new businesses, lowered registration fees and reduced the minimum capital requirements for registration.

The creation of the Industrial Modernization Center at the Ministry of Trade and Industry in 2000 and its merger in 2017 with the Social Fund for Development to create the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency (MSMEDA) provided a focus for SME promotion efforts within the bureaucracy.

These efforts were given a significant boost when the Egyptian central bank introduced its SME initiative in 2008. At first, the initiative exempted loans extended to SMEs from the reserve requirements of Egyptian banks. In 2016, the central bank expanded the initiative by requiring Egyptian banks to increase lending to SMEs to 20% of their total loan portfolio by the end of 2020. It also capped interest rates for SME lending at very low levels, ranging from 5% for small businesses to 12% for mid-sized firms. Finally, the central bank, through the Credit Guarantee Company, created a guarantee trust fund of two billion Egyptian pounds targeted at SMEs (Fitzgeorge-Parker, 2018).

These reforms appear to have improved access to credit for SMEs. Egypt’s rank in the World Bank’s Doing Business report on this dimension improved from 159 in the world in 2007 to 60 in 2019 (World Bank, 2006, 2019).

While these are very important initiatives that are likely to have contributed substantially to the growth of the SME sector in the past decade, more needs to be done to sustain and promote growth of the sector.

One area in need of improvement is the tax payment system. Egypt is doing poorly compared with other countries in the ease of paying taxes index, according to the World Bank’s Doing Business report, which ranks Egypt at 159 in the world in 2019, 15 places behind where it ranked in 2007 (World Bank, 2006, 2019). The difficulty of tax payments and the unpredictability of the tax burden are probably the main reason why firms in Egypt want to remain informal, which often means staying small.

Likewise, time and cost to enforce contracts significantly hinders SME growth in Egypt. According to the Doing Business report, Egypt ranks 160 in the world in this dimension, three places behind where it was in 2007. The average time taken to resolve a claim is almost three years, and the average cost is 26% of the value of the claim.

Policies to reduce the cost of formality and making these costs variable with firm size rather than fixed would allow micro firms to expand and would contribute to the re-emergence of the missing middle.

Such policies should include streamlined health and safety regulations, predictable and rule-based tax administration, easing licensing requirements and digitalisation of official transactions. Besides making the business environment less onerous and more predictable for SMEs, these reforms would reduce the degree of bureaucratic discretion, leading to less corruption and more efficient taxation and regulation.

The re-emergence of the missing middle is undoubtedly one of the most positive economic developments in Egypt in recent years. It has the potential to reverse years of anaemic private sector growth and increased informalisation of employment. Although much has already been done to promote this trend, considerably more policy action is needed to institute a business climate in which Egypt’s multitude of micro enterprises can grow into small and eventually medium-sized enterprises.

Further reading

Fitzgeorge-Parker, Lucy (2018) ‘Central Bank Drives Lending Bonanza for Egypt’s SMEs’, Euromoney, 2 October.

World Bank (2006) Doing Business 2007: How to Reform.

World Bank (2019) Doing Business 2019: Training for Reform.