In a nutshell

Egyptian women, especially those living in rural areas, have low rates of economic participation by standard measures.

Standard measures underestimate the economic engagement of rural women; married women work a ‘second shift’ of domestic responsibilities.

‘Graduation’ programmes, providing livestock as assets and addressing the multitude of other constraints facing women, are a promising strategy for supporting Egyptian women.

Women in Egypt have low rates of economic participation by standard measures. Although the country has made enormous progress in ensuring gender equity in health and education, it has not done so in economic engagement (World Bank 2018). In 2018, while 72% of men aged 15-64 were employed, only 17% of women were employed (Krafft et al, 2019a). Despite women’s rising educational attainment, their employment has declined over time (Assaad et al, 2018; Krafft et al, 2019a).

Women’s economic participation is underestimated

International labour statistics standards define employment as ‘work for pay or profit’ – that is, engagement with the market (ILO, 2013). Measuring this definition has well-known challenges, particularly for rural women (Langsten and Salem, 2008).

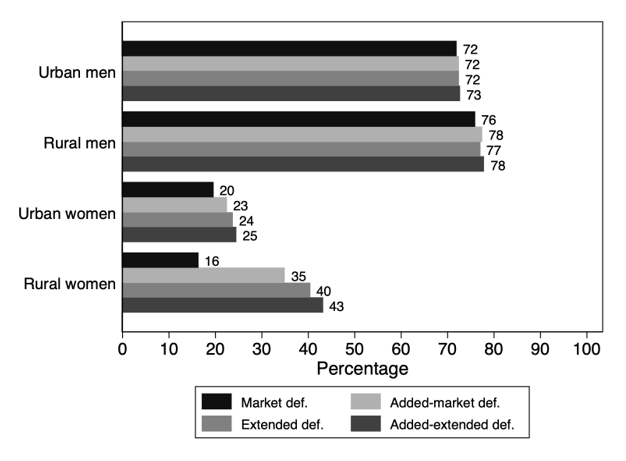

Figure 1 shows employment rates from the new Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) 2018 wave, using the market definition of employment (and other definitions). Under the market definition, 72% of urban men and 76% of rural men work, while only 20% of urban women and 16% of rural women work.

The extended definition of employment adds subsistence work (processing of primary commodities for own consumption, for example, agriculture and animal husbandry). This measure changes men’s employment rates very little, but urban women’s employment increases from 20% to 24% and rural women’s employment increases from 16% to 40%.

Figure 1: Standard measures underestimate rural women’s employment

Employment to population ratios (percentages) when adding individuals who worked for a family enterprise or farm to the market and extended definitions by sex and location, aged 15-64

Notes: The added-market definition of employment adds individuals who worked on a family enterprise or farm that sold crops or animals they worked with to the market definition of employment. The added-extended definition of employment adds individuals who worked on a family enterprise or farm (not conditional on selling crops or animals) to the extended definition of employment. Individuals were only considered working on a family enterprise or farm if they were one of the (up to) three primary workers for one or more animal, crop, or non-farm enterprise.

Source: Krafft et al (2019b) based on ELMPS 2018.

In ELMPS 2018, there are a series of questions on households’ engagement with a non-agricultural enterprise, crops or animals. These questions also include information on whether the crops or animals are sold, and who works on the enterprise, crops or animals.

Although these cover slightly different (longer) periods of time than the market employment questions, we would not expect large differences in economic engagement. But when we add individuals working on enterprises, crops or livestock (with market sales) to the market definition of employment, in Figure 1, employment rates increase substantially for rural women: from 16% to 35%.

The typical implementation of measuring market employment misses the majority of rural women’s engagement with the market economy. Moreover, most of what is detected as subsistence work (extended employment) is actually engaged with the market.

Accurate statistics on women’s employment are critically important to understanding the economy and tracking progress on gender equality. Measures such as those in the ELMPS modules, which capture rural women’s economic engagement more effectively, should be considered for inclusion in international labour statistics.

Married women work a ‘second shift’ of domestic responsibilities

While men may spend more time contributing to the economy through market work, married Egyptian women work an entire ‘second shift’ of domestic responsibilities. These contributions are left out of typical economic measures, such as GDP (Waring, 1990).

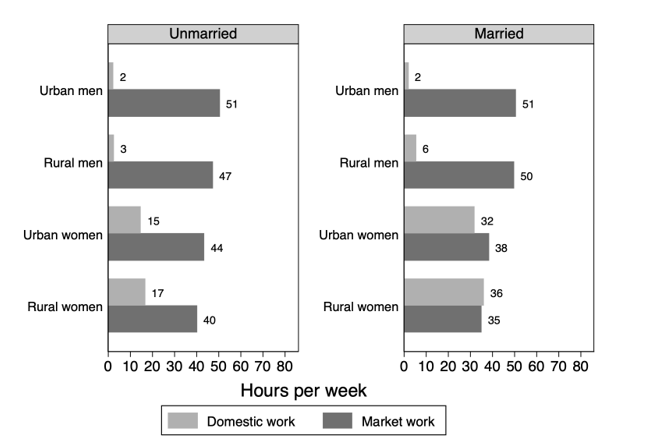

Figure 2 shows the hours per week spent on domestic responsibilities. Whether married or unmarried, living in urban areas or rural areas, men spend only two to six hours per week on domestic responsibilities, such as washing dishes, cooking, cleaning or care-giving.

Unmarried women work 15-17 hours per week in such responsibilities, which is already difficult to reconcile with market work of 40-44 hours per week, for those who work. Married women face even longer hours of domestic responsibilities: 32-36 hours per week.

Figure 2. Married women work an entire “second shift” of domestic responsibilities

Hours spent doing domestic work (all individuals) and market work (employed individuals) per week by sex, location and marital status, aged 15-64, 2018

Notes: The reference period for both domestic work and market work is the last seven days. Unmarried includes never married, contractually married, divorced and widowed. Domestic work includes: agricultural activities or raising poultry or livestock; producing ghee, butter, cheese or non-food goods; collecting firewood or other fuel or water; cooking; washing dishes; doing laundry and ironing; managing your household; cleaning your house; construction/repairs; shopping (food, clothing, etc.); caring for sick or elderly (only); and taking care of children (only).

Source: Krafft et al (2019b) based on ELMPS 2018.

The ‘second shift’ makes it very difficult for women to hold a full-time job, particularly in the private sector, which requires longer hours (Assaad et al, 2019). The longer hours may be one of the reasons why women leave the private sector at marriage, but persist in the public sector and non-wage work, which are more reconcilable with their domestic responsibilities (Assaad et al, 2017; Krafft et al, 2019a; Selwaness and Krafft, 2018).

In order for women to achieve economic equity, men will need to do a greater share of domestic responsibilities. Some of these responsibilities may also be able to be shifted onto the market – for example, through time-saving technologies, such as prepared meals, or market services, such as childcare and cleaning services (Krafft and Assaad, 2015).

Graduation programmes can lift women out of poverty

A new approach to economic empowerment – ‘graduation’ programmes – shows enormous potential for women, especially those who are poor and living in rural areas in Egypt. Graduation programmes recognise that there are a variety of aspects of economic marginalisation, and work to tackle all of these aspects in a blended, integrated programme (BRAC, 2016).

The programmes typically target the poorest households in a community, and provide them with a productive asset, training and support for that asset, as well as health, consumption, savings and general life skills support (Banerjee et al, 2015). This multidimensional approach has shown consistent impacts around the world, reducing poverty and improving wellbeing.

Egypt is building graduation programmes into its Forsa programme, designed to graduate impoverished families from the existing Takaful and Karama cash support programmes of the Ministry of Social Solidarity (World Bank, 2018). The Sawiris Foundation for Social Development and other local partners are piloting Bab Amal, a graduation programme in Upper Egypt (BRAC et al, 2019). This programme is being tested through a randomised evaluation to understand its impact.

While we await the results of the evaluation, in order to consider whether such a programme might work in Egypt, and particularly for poor women, it is helpful to assess whether the local conditions align with success elsewhere (Bates and Glennerster, 2017).

Women, and particularly poor rural women in Egypt, face multiple constraints on their economic engagement, suggesting that the multi-pronged approach of graduation programmes is needed. Non-wage work, including self-employment, is easier to reconcile with women’s substantial domestic responsibilities, and women are already caring for livestock despite inequitable gender roles towards employment generally (Krafft et al, 2019b).

The Bab Amal programme will include training on gender equality (BRAC et al, 2019), which, together with increasing women’s assets and economic empowerment, may ultimately lead to Egypt being as equitable in employment attitudes and practices as it is in education.

Further reading

Assaad, Ragui, Abdelaziz AlSharawy and Colette Salemi (2019) ‘Is The Egyptian Economy Creating Good Jobs? Job Creation and Economic Vulnerability from 1998 to 2018’, Economic Research Forum Working Paper Series (forthcoming).

Assaad, Ragui, Rana Hendy, Moundir Lassasi and Shaimaa Yassin (2018) ‘Explaining the MENA Paradox: Rising Educational Attainment, Yet Stagnant Female Labor Force Participation’, IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 11385.

Assaad, Ragui, Caroline Krafft and Irene Selwaness (2017) ‘The Impact of Marriage on Women’s Employment in the Middle East and North Africa’, ERF Working Paper No. 1086.

Banerjee, Abhijit, Esther Duflo, Nathaniel Goldberg, Dean Karlan, Robert Osei, William Pariente, Jeremy Shapiro, Bram Thuysbaert and Christopher Udry (2015) ‘A Multifaceted Program Causes Lasting Progress for the Very Poor: Evidence from Six Countries’, Science 348 (6236).

Bates, Mary Ann, and Rachel Glennerster (2017) ‘The Generalizability Puzzle’, Stanford Social Innovation Review.

BRAC (2016) ‘Targeting the Ultra Poor Programme Brief 2016’.

BRAC, Sawiris Foundation and J-PAL (2019) ‘Bab Amal Design Report’.

ILO (2013) ‘Resolution Concerning Statistics of Work, Employment, and Labour Underutilization Adopted by the Nineteenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians (October 2013)’.

Krafft, Caroline, and Ragui Assaad (2015) ‘Promoting Successful Transitions to Employment for Egyptian Youth’, ERF Policy Perspective No. 15.

Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad, and Caitlyn Keo (2019a) ‘The Evolution of Labor Supply in Egypt from 1988-2018: A Gendered Analysis’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Krafft, Caroline, Caitlyn Keo and Luca Fedi (2019b) ‘Rural Women in Egypt: Opportunities and Vulnerabilities’, ERF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Langsten, Ray, and Rania Salem (2008) ‘Two Approaches to Measuring Women’s Work in Developing Countries: A Comparison of Survey Data from Egypt’, Population and Development Review 34 (2): 283-305.

Selwaness, Irene, and Caroline Krafft (2018) ‘The Dynamics of Family Formation and Women’s Work: What Facilitates and Hinders Female Employment in the Middle East and North Africa?’, ERF Working Paper No. 1192.

Waring, Marilyn (1990) If Women Counted: A New Feminist Economics, Harpercollins.

World Bank (2018) ‘Women Economic Empowerment Study’.