In a nutshell

Sectors of Lebanon’s economy in which more than half of all firms are politically connected are less affected by a downturn in the overall economy.

Real estate might be the game-changer in the current downturn, as the only major sector with a high share of politically connected firms that suffers from a gradual decline in activity and output.

On several occasions in the past, Lebanon has been bailed out by international support when economic conditions became untenable: with declining interest in the country from Europe and the Gulf countries, this time might well be different.

Lebanon’s post-war financial and economic woes are perennial. Initially triggered by the spillover effects of the Syrian crisis in 2011, macroeconomic and financial indicators were set on an utterly unsustainable path.

Government debt exploded after prolonged political gridlock led public spending to skyrocket to what is forecast to be more than 158% of GDP by 2021 (World Bank, 2019). Combined with increased exposure to external debt and rising interest rates, economic growth may tip into recession this year.

In short, crisis looms.

In an effort to rally support for painful reform to stabilise the country’s gloomy finances, the government of Prime Minister Saad Hariri recently declared a ‘state of economic emergency’. President Michel Aoun has accommodated the efforts and calls for ‘sacrifices to be made by everyone’. Lebanon’s elites finally seem to be eager to reform.

Understandably so, because in Lebanon the personal wellbeing of the political elites is highly dependent on the wellbeing of the economy. As analysis by Ishac Diwan and Jamal Haidar (2019) shows, of firms with more than 50 employees, 44% are politically connected and have a board member who is a relative or close friend of a member of the political elite.

The few reforms that passed, however, involve little structural change that could, for example, improve the competitiveness of the private sector or curb tax evasion. Instead, the costs of economic distortion continue to be socialised via tax exemptions (Atallah and Mahmalat, 2019) or high interest rates (Salti, 2019). Despite the economic challenges, political actors still benefit excessively from the status quo.

In July, for example, seven months into the new year, the parliament ratified what it called an ‘austerity budget’ for 2019. The budget introduced a number of expenditure cuts and revenue increases that aim to restore the confidence of investors and the international community into a government eager to reform.

But as recent research by the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies shows, the budget law only formally curbs the budget deficit. It leaves untouched the structural conditions that gave rise to the economic deterioration in the first place, such as a regressive tax regime that exacerbates existing inequalities and crowds out much-needed public investments (Mahmalat and Atallah, 2018).

Proposals to tax the salaries, benefits and pensions of current and former politicians were dismissed during the political bargaining. Amendments to increase the fees on tinted car windows and the licences to carry guns, widely used among the security entourage of politicians, vanished in the final documents. Expenditure targets are achieved by simply deferring the bill of investment projects to the upcoming years.

But when the wellbeing of political elites, in fact their very survival, is so highly dependent on the wellbeing of the economy, why would they delay more structural efforts to contain the budget deficit or make the tax regime more efficient? The high degree of their entrenchment in key sectors of Lebanon’s economy calls into question how political elites calculate the opportunity costs of political gridlock.

In other words, why is Lebanon’s stabilisation delayed?

Research on the political economy of reform explains the delay of stabilisation as a consequence of the struggle of powerful interest groups to shift the cost of reform onto each other. Precisely because reform comes at a cost for elites, they prolong political bargain by embarking on a ‘war of attrition’ (Alesina and Drazen, 1991). Stabilisation, or a change in the status quo, occurs when economic conditions deteriorate sufficiently so that one of the groups concedes and bears a higher burden of the costs.

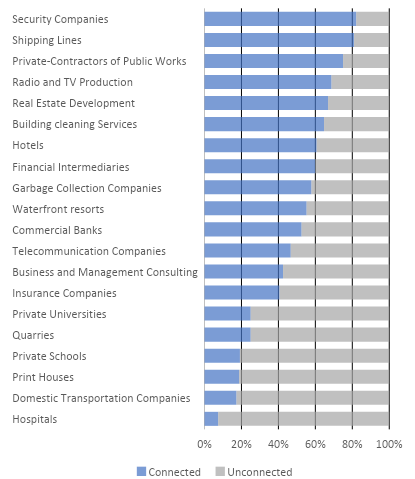

To understand the war of attrition among Lebanese elites, one must look at the structure of their entrenchment with the private sector. Politically connected firms concentrate in sectors that are not (or are relatively less) affected by a downturn of the overall economy (see Figure 1). Economic conditions, at least until recently, simply exerted little pressure for actors on a personal basis to concede and to bear the costs of reform.

Disaggregating the data provided by Diwan and Haidar (2019) shows that an economic downturn leaves sectors in which more than half of all firms are politically connected comparably well off. (We excluded from the analysis sectors with fewer than 10 firms in total.)

Take the hospitality sector, for example. Firms running hotels and waterfront resorts are, respectively, 61% and 55% connected to political elites. Passenger numbers at Beirut’s airport increased constantly over the past years, while the number of tourists increased by almost 45% from 2012 to 2017. Accordingly, hotels and waterfront resorts recorded a major improvement in their booking records. The occupancy rates of four and five-star hotels in Beirut reached 69.2% (up from 58.9% in 2018) while the average room yield rose by 29.9%.

Figure 1: Share of politically connected firms with more than 50 employees in sectors with more than 10 firms

The banking sector is another example. Benefiting heavily from the huge margins paid by treasury bills, the profitability of domestic banks remained – until recently – almost unabated. In 2017, Lebanese commercial banks significantly expanded their profits, reaching a return on average equity of above 11.2% for the group of major banks.

Despite the challenging macroeconomic environment and the difficulties that sky-high interest rates impose on the Ministry of Finance’s ability to repay its debt, the return on average equity for the sector as a whole (10.8%) is on par with the 11% average of banks in the Middle East and North Africa (Barakat, 2018).

Other sectors are structurally less affected by an economic downturn and exhibit a low elasticity of demand. Security companies, for example, are employed by politicians, business people and other public figures, for whom security remains a necessity in the face of prevailing political and security uncertainty (US Commercial Service, 2016). The same holds for garbage collection, which continues to be collected at sky-high rates.

Shipping lines are also spared much of the effects of Lebanon’s economic woes, since foreign trade activity must be done by ship after the closure of land routes through Syria in 2011. In fact, the number of vessels at Beirut’s port remained almost constant between 2012 and 2018. Public works and investments enjoy rosy prospects due to internationally funded major capital investment programmes worth almost 40% of GDP.

The game-changer, however, may be the real estate sector. Real estate is the only major sector with a high share of politically connected firms that suffers from a gradual decline in activity and output. Since the boom year of 2010, the area of new construction permits has almost halved until 2018: from 17,625 to 9,020 thousand square metres.

Slowing demand lowers the value of sales transactions, which plummeted by 40% from $4,504 million to only $2,726 million in the first six months of 2017 to 2019. Given the central role that the real estate sector plays in Lebanon’s economy – at 15%, the largest contributor to national GDP – a collapse of major real estate developers could well be the tipping point for the economy to crash.

History might repeat itself. On several occasions in the past, Lebanon was bailed out by international support when conditions became untenable. Lebanese elites seem to assume that the country remains ‘too small to fail’ for influential regional players.

But with declining interest in the country from Europe and the Gulf countries, this time might well be different. This time, the war of attrition would not only be lost by Lebanese citizens by suffering through prolonged periods of economic stagnation. As other crucial sectors started to follow the declining trend, uncertainty about the integrity of the pillars of the Lebanese economic model threaten both economic and political stability. Without concerted effort, Lebanon’s elites cannot win this war either.

Further reading

Alesina, Alberto, and Allan Drazen (1991) ‘Why Are Stabilizations Delayed?‘, American Economic Review.

Atallah, Sami, and Mounir Mahmalat (2019) ‘Tax Exemptions Would Undermine Faith in New Government’s Pledge to Reform’, Al Akhbar.

Barakat, Marwan (2018) ‘Banking Industry 2017: An Analysis of Activity Performance, Risk Profile and Return Indicators’, Bank Data.

Diwan, Ishac, and Jamal Haidar (2019) ‘Do Political Connections Reduce Job Creation? Evidence from Lebanon’, in Ishac Diwan and Adeel Malik (eds) Crony Capitalism in the Middle East – Business and Politics from Liberalization to the Arab Spring, Oxford University Press.

Mahmalat, Mounir, and Sami Atallah (2018) ‘Why Does Lebanon Need CEDRE? How Fiscal Mismanagement and Low Taxation on Wealth Necessitate International Assistance’, Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

Salti, Nisreen (2019) ‘No Country for Poor Men: How Lebanon’s Debt Has Exacerbated Inequality’, Carnegie, 17 September.

US Commercial Service (2016) ‘Doing Business in Lebanon: 2016 Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies’.

World Bank (2019) ‘Lebanon’s Economic Update – April 2019’.