In a nutshell

The decision to migrate occupies the minds of a large share of MENA workers, and plays an important role in their career aspirations, prospects and actual outcomes.

Return migrants in Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia find employment in higher-earning occupations and are more intergenerationally mobile than non-migrants – but this seems to be largely a result of self-selection.

Prospective migrants may invest more intensively in globally marketable qualities – such as soft skills, sociability and adaptability – which allow them to outperform non-migrants in all stages of their careers.

Most migration in and around the MENA region is return migration. The temporary absence of migrants from their countries’ labour markets and their eventual return affect the employment prospects of workers and their peers, as well as the broader operation of the labour market.

Migration is also a piece of what the World Bank calls the ‘Arab inequality puzzle’ – that while objective measurements of inequality are low and stable, people protest against high and rising inequality. Understanding how migration is caused and how it affects the economic status of migrants and non-migrants in various regions is crucial for evaluating MENA development, workers’ economic mobility and the state of social justice.

MENA migration flows

MENA migration flows are significant in their volume and systematic nature. Over 10 million MENA citizens (10% of the working-age population) reside abroad, mostly as temporary labourers in the Gulf or entrepreneurs and professionals in Europe. International remittances account for significant shares of countries’ GDP.

Emigration also affects the performance of MENA labour markets. For example, it can result in a rise in skill acquisition in regions with many aspiring migrants, a fall in unemployment rates among fresh graduates thanks to the emigration of some of their peers, but also a ‘brain drain’ in terms of workers’ skills (David and Marouani, 2016).

Migrants are predominantly young men who have finished their formal education, and their migration is typically temporary. Nearly half of them return home before the age of 40; and over two-thirds before the age of 50.

According to surveys of public perceptions, 28% or even as much as 50% of MENA youth express a willingness to emigrate temporarily to improve their employment prospects and their families’ wellbeing. The decision to migrate thus occupies the minds of a large share of MENA workers, and plays an important role in their career aspirations, prospects and actual outcomes.

At the same time, the directions of migration, and migrants’ profiles indicate systematic selection of workers into migration because cross-border migration is risky, as well as being financially and socially costly (Wahba, 2015).

It is thus important to understand what induces certain workers to migrate, and how migration (or inability to migrate) affects their economic outcomes, as well as the labour market conditions in their countries of origin and destination. This is policy-relevant, especially because national governments and, to some extent, international organisations have an active role to play in managing and directing the flow of migration, and providing support for prospective, present and past migrants.

New evidence

In a recent study (Hlasny and AlAzzawi, 2018), we assess the demographics of return migration and its contribution to workers’ own lifetime earnings and intergenerational socio-economic mobility, based on the conjecture that migration can bestow on them opportunities for skill and capital acquisition that non-migrants do not receive.

Our analysis covers three Arab countries for which six high quality, harmonised labour market panel surveys are available: Egypt (1998, 2006 and 2012); Jordan (2010 and 2016); and Tunisia (2014). These three countries provide interesting case studies, and show a mosaic of migration trends and impacts across disparate parts of the region.

Focusing on working-age men, we compare their current socio-economic outcomes – earnings; employment status; household ownership of productive and non-productive assets; and residence status – to their status in prior years and their fathers’ outcomes.

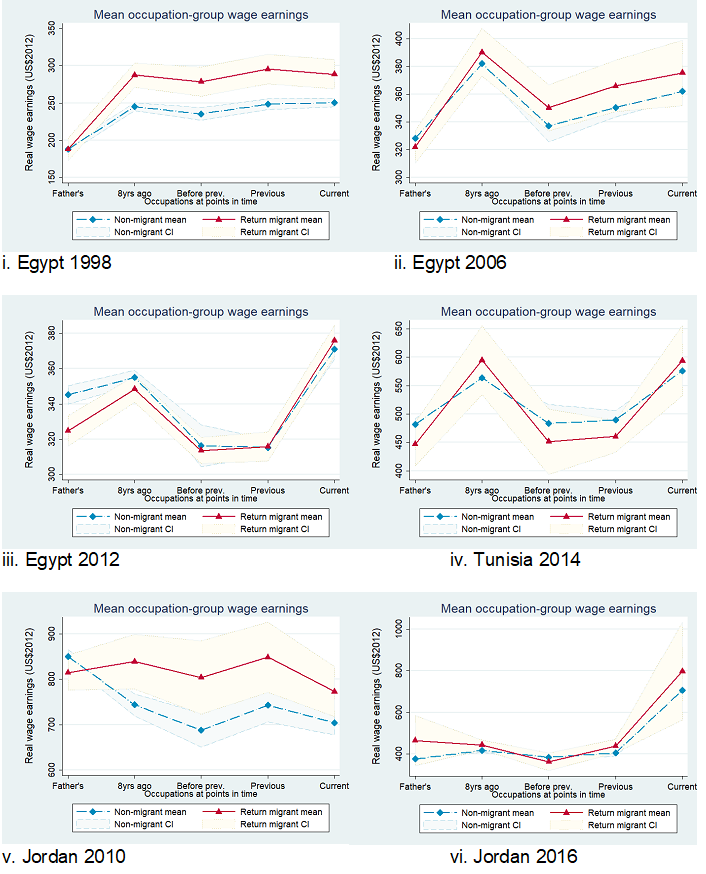

By tracking workers’ occupations over time and across generations (and imputing typical earnings in those occupations in different years), we can quantify workers’ earnings paths across time and generations, and compare them between migrants and non-migrants. Finally, we mitigate the problem of self-selection of workers into migrating, in order to identify the stand-alone impact of migration on workers’ outcomes.

Results

We find that migrants’ choice of destination is driven by economic, geographical and historical considerations. Prospects of work authorisation, labour demand factors, and the presence of enclaves of workers from one’s native community in the destination country are among the important factors at play.

Migration trends differ systematically between Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia, as well as over time, in their prevalence, form and impact on workers’ socio-economic outcomes. For example, migrant flows from Egypt are concentrated in a few destinations, but those from Jordan are diffuse. This is because of differences in the job-search methods used by migrants and the type of work sought.

Migration flows from Egypt are ‘negatively selected’: compared with non-migrants, migrants are the less educated, and predominantly residents of rural and disadvantaged regions who migrate for specific temporary employment opportunities in the Gulf countries. Migration from Jordan, in contrast, is ‘positively selected’: it is the educated workers from cities who consider entrepreneurship and career advancement in an array of host countries in Europe and beyond.

Egyptian migrants rely on networks of past migrants in destination countries to help them get settled, while Jordanian migrants apply for positions unassisted. Migration from Tunisia represents an intermediate case of migration to a narrow group of destinations, by workers who are as educated as non-migrants, yet less likely to be rural.

Around the time of the Arab Spring, in a sign of a changing regional order, these migration trends became less polarised across countries. Migration flows from Jordan became less diffuse between 2010 and 2016, while those from Egypt became less concentrated.

In terms of workers’ present status, return migrants in all three countries find employment in higher-earning occupations and are more intergenerationally mobile than non-migrants. Return migrants also reside in more urbanised areas and privileged regions, and achieve other desirable socio-economic outcomes relative to non-migrants.

Comparing workers’ present outcomes with those of their fathers also shows that return migrants in all three countries tend to have lower-earning parents, but are more intergenerationally mobile and attain higher earnings than non-migrants.

Looking at (relative) transitions of workers between the earnings quintiles of their fathers, and their own current quintiles, we find that the transitions of return migrants are more diverse and more likely to be upward than those of non-migrants, indicating greater intergenerational earnings mobility. This can largely be attributed to the lower economic position of return migrants’ fathers.

But the link between migration and economic mobility appears to be just an association driven by mediating factors, and is not causal. Return migrants outperform their peers not only currently but also before their migration spell – in their previous occupation, the occupation before that and their occupation eight years in the past – and their earnings premium does not evolve monotonically.

Workers who had migrated did not systematically earn more eight years ago than workers who would end up migrating only later. This suggests that individual-level characteristics or predisposition for migration contribute more to workers’ outcomes than the migration experience itself.

Figure 1 illustrates the typical (absolute) earnings paths of return migrants and non-migrants across multiple points in time. While return migrants typically have lower-earning fathers, they themselves outperform non-migrants at all points in time, regardless when their migration spell occurred. Return migrants thus appear more intergenerationally mobile, but no more mobile within their lifetimes than non-migrants.

After controlling for workers’ characteristics and pre-existing circumstances, and particularly after removing the endogenous part of workers’ migration decision, the earnings premium due to migration disappears. The destination and duration of migration do not appear to affect post-migration earnings either, corroborating the story that earnings mobility is a result of self-selection and return on workers’ time-persistent qualities.

At the same time, our findings do not point to inequality of opportunities for migration based on parental economic outcomes, since migrants appear to come from lower-earning families than non-migrants. Instead, the findings point toward latent individual-level predispositions or enduring effects of planned future migration as sources. The relevant qualities do not appear correlated with the economic status of workers’ fathers, but they may have contributed to workers’ outcomes over a range of years, ever since their entry into the labour market.

One possible interpretation is that prospective migrants – say, those growing up in localities with dense networks of return migrants – invest more intensively in globally marketable qualities, such as soft skills, sociability and adaptability, beyond those revealed by their educational attainment. These qualities may allow eventual migrants to outperform non-migrants at all stages of their careers regardless when the actual migration spell took place or how long it lasted.

The lack of causation is identified for prime-age male citizens, but questions remain about the effects among marginalised groups, such as married women, fresh graduates, non-citizens or people near retirement.

Restricting our attention to prime-age men simplifies our analysis and makes our results easier to interpret, but clearly it would be highly policy-relevant to understand the career investments and mobility of various marginalised groups. In fact, in all three countries, migrants come from disadvantaged regions and lower-earnings families, suggesting a certain degree of disenfranchisement that may be motivating them to search for employment abroad.

Implications and recommendations

It may be surmised that the prospect of migration has a beneficial role with respect to workers’ motivation, as well as employer-worker matching and negotiation, counteracting intergenerational transmission of status and inequality in society.

The prospect of migration may be outside workers’ sphere of choice, but it affects their investment in skills and their eventual performance. The facility to migrate gives workers an option to respond to labour market conditions at home and abroad, and motivates them to accumulate globally marketable qualities.

Moreover, return migration produces important spillovers for home and destination labour markets, and for those left behind. The reduction in domestic labour supply and the upward pressure on wages, combined with wage stickiness even after migrants return, may contribute to our finding that there is little return on migration for the migrants themselves, even if non-migrants or indeed all workers benefit.

For the migration benefits to accrue to individuals other than those predisposed for migration and economic success, civil society and government agencies should deploy resources that enable even disadvantaged workers to partake in the opportunity, as it may enhance their careers and family wellbeing, as well as the healthy organisation of society. Providing loans, verified-jobs boards, transparent worker-sponsorship schemes or other assistance to prospective migrants would go a long way towards levelling the economic opportunities for all.

We know that regulated migration helps to improve and balance labour market conditions across geographies, and at the same time can offer short-term benefits to destination countries without subjecting them to long-term political risks. The home and destination countries can both benefit from coordinated intergovernmental and inter-agency efforts enabling and managing informed flows of migration across the MENA region and beyond.

Further reading

David Anda, and Mohamed Ali Marouani (2016) ‘The Impact of Emigration on MENA Labor Markets’, ERF Policy Brief No. 21.

Hlasny, Vladimir, and Shireen AlAzzawi (2018) ‘Return Migration and Socioeconomic Mobility in MENA: Evidence from Labour Market Panel Surveys’, UN University WIDER Working Paper 2018/35 (March).

Wahba, Jackline (2015) ‘Selection, Selection, Selection: The Impact of Return Migration’, Journal of Population Economics 28(3): 535-63.