In a nutshell

Technological innovation in robotics and artificial intelligence can cause substantial dislocations for workers and labour markets; but in the long run, it can bring about higher incomes and quality of life, including more leisure.

The negative effects can be mitigated and the positive impact realised only if public institutions promote equality of opportunities, generate an educational system that favours flexible skills and creativity, and use redistribution policies to share the proceeds of technological gains.

With proper public institutions, instead of raging or racing against the machine, we can race with the machines toward a better future.

The fear: are we running out of jobs?

There are growing fears that emerging breakthroughs in technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics will lead to the wholesale replacement of human workers by machines and an era of mass joblessness and, even wider income inequality.

History widely documents that workers’ jobs and livelihoods have been affected by machines – as seen in the First Industrial Revolution in the 1750s and, more recently, in the strikes by taxi drivers protesting against on-demand car services, such as Uber. The fear of losing our jobs due to obsolescence may be one of our greatest fears – and for a good reason: job loss has significant and long-lasting negative effects on future employment, earnings, consumption, health and even life expectancy.

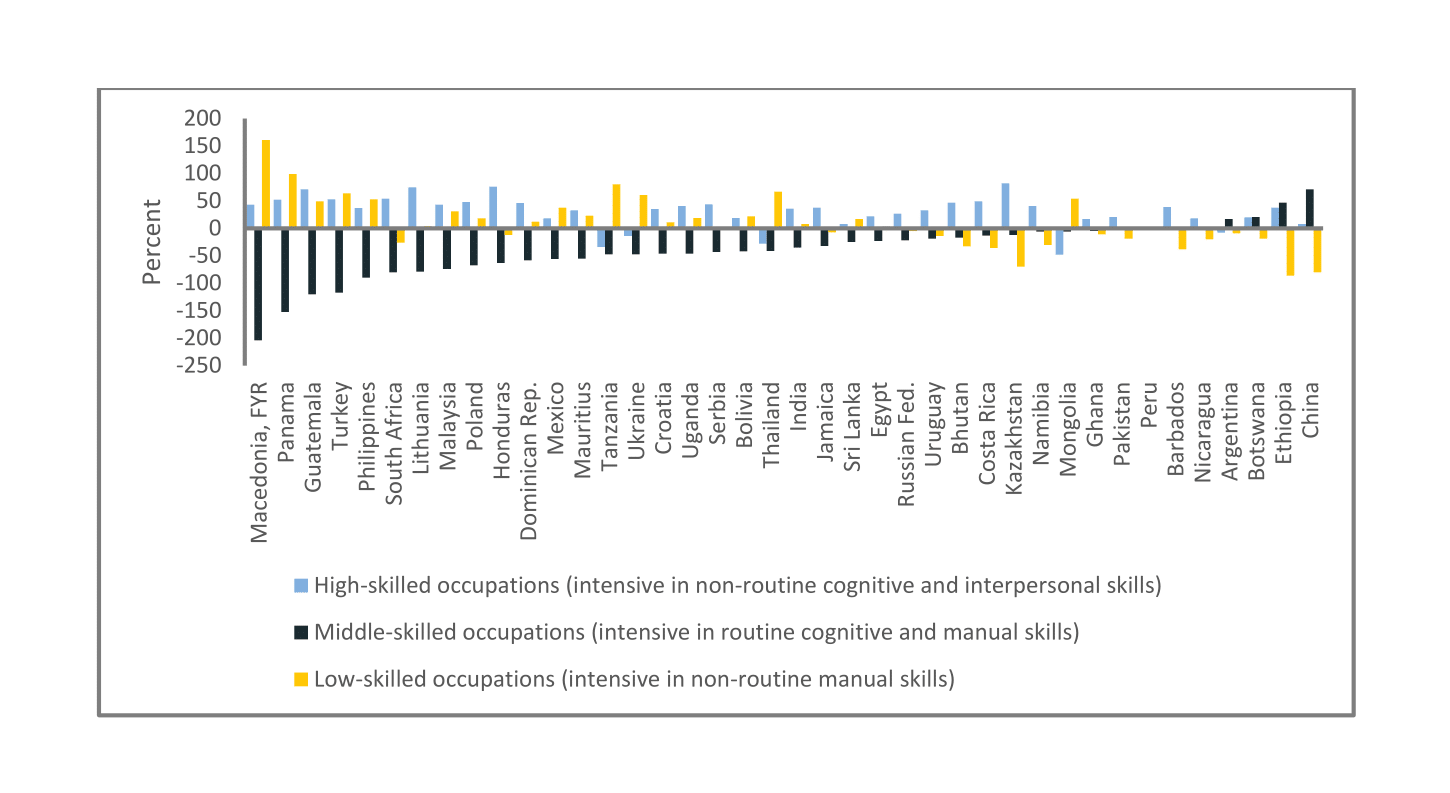

What determines vulnerability to automation is not so much whether the work concerned is manual or white-collar but, whether it is routine. Employment growth in many countries has followed a U-shape in recent decades or termed as ‘job polarisation’.

In such cases, the middle-skill jobs are declining but, both low- and high-skill jobs are expanding. While the U-shape holds for many developing countries, the outcome of the relationship between employment growth and the skills distribution depends on the local labour market conditions, the existing skills distribution and adoption of technologies (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Annual average change in employment share, circa 1995-2012

Source: World Bank 2016.

The past of work: have we been here before?

The predictions that automation will make humans obsolete have been made before, going back to the past three Industrial Revolutions – the 1760s; the 1890s; and the 1970s. Each has been characterised by technological innovations: the first by steam engines and the mechanisation of factory production; the second by electricity; and the third by using electronics and information technologies in production.

These past Industrial Revolutions led to large productivity improvements, which in turn significantly raised welfare in developed countries, in terms of both material living standards and leisure. But material living standards and leisure in developing countries lag far behind those in developed countries – which suggests that the developing countries stand to gain more from technology-driven productivity growth.

Nonetheless, productivity gains take time to materialise. In the case of electricity, the productivity boom occurred only in 1920s, over 30 years after factory electrification. We saw a similar trend for information technologies that started in 1970s and only had a visible impact in the 2000s.

This long gestation is a phenomenon that is observed for most technologies. It is particularly pronounced for ‘general purpose technologies’, as production processes need to transform and adapt to reap the benefits of such technologies.

Yet in the past 250 years the warnings of technological unemployment have been assuaged by the economic response to automation. Selected jobs in selected sectors may disappear but new jobs have also been created.

For example, in the United States, farming went from being the main employer in the economy, with 41% of all jobs in 1900, to employing only 2% of workers in 2000. Over this century, productivity gains allowed agriculture to feed a growing population with fewer workers, while the rise of new economic activities created better-paying jobs and opportunities in the cities for all workers.

The positive labour effects of such shifts typically take decades to materialise and as in the past, there was a long period of time when wages and employment fell or remained stagnant despite the adoption of new technologies and increases in productivity. The long pause – known as ‘Engels’ pause’ – has caused labour disruption, social unrest and even political revolutions.

The future of work: is this time different?

No Industrial Revolution has the same labour market effects as the preceding ones. The pessimists’ view of machines taking all jobs and the optimists’ view of technology creating new ones generate a heated debate among policy-makers, technology experts and civil societies. While it is hard to predict the future, the implications of the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ is broader-based as machines can now perform non-routine tasks that apply human logic and information.

The evidence of disruption is seen in the Philippines. Some companies in the business process outsourcing industry have recently begun replacing call centre agents by chatbots powered by AI systems. While the impact of technological change is for the moment mostly evident on relatively low-skilled ‘process-driven’ business outsourcing, there are widespread fears of more general impacts in the medium term.

This does not mean that machines will replace all labour or that wages will plummet across the board. Computers based on AI are remarkably effective in conducting specific tasks rather than replicating human intelligence. The human contribution is likely to remain a crucial ingredient (see Autor, 2015).

Moreover, the replacement of labour by machines takes time, and depends on specific circumstances, such as the relative cost of labour and the different stages of development of a country (see World Bank, 2018).

A framework to assess the impact of technological innovation on jobs and wages

To assess the effects of technology on employment and wages, innovations are categorised into enabling technologies and replacing technologies (see Acemoglu and Autor, 2011, and Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2018). Enabling technologies expand the productivity of labour, and lead to higher employment and wages. Replacing technologies, in contrast, substitute for labour, making workers less useful and lowering their wages.

While the direct effect of replacing technologies is negative on wages and employment, it can still have a positive effect in two main ways:

- First, the new technologies can generate complementary tasks.

- Second, the productivity effects can be sufficiently large to create wealth and generate demand for other jobs.

Ultimately, the effects of technology do not depend only on the properties of technology, but its interaction with the workers’ abilities and the conditions of labour markets. Rigid labour markets tend to adjust by shedding labour, while more flexible labour markets adjust through wage reductions.

Flexible labour markets can also induce workers’ reallocation and mobility in the face of technological shocks, mitigating negative effects on both employment and wages.

Policy implications

Technological change promises tremendous gains in productivity and welfare. No doubt history shows that the transition for workers will be difficult, and even more so in the advent of AI. Therefore, policies should focus on maximise its potential social gains and making it easier for workers to acquire new skills and switch jobs, if needed. This requires policies that facilitate labour market flexibility and mobility, introduce and strengthen safety nets and social protection, and improve education and training.

Policies that make labour unduly expensive induce the adoption of labour-replacing technologies. Labour market reform should be directed at facilitating labour flexibility and mobility, including international migration.

Similarly, getting the basic business environment right for firms to invest and hire workers, and reducing market failures hindering start-ups, can help to capture the gains of technological change. The policy principle should not be to protect obsolete jobs, but to protect people.

Safety nets are essential to support workers (and their families) who are displaced or replaced when new technologies are implemented. In the long run, broader redistribution policies may be desirable to make sure that the technological dividends are spread around the population, making everyone an ‘owner’ of the current and potential technologies.

Educational reform – emphasising scientific, mathematical and communication abilities, as well as softer skills such as perseverance, flexibility, creativity, adaptability and teamwork – is crucial to develop the complementary skills that workers need to benefit from all types of machines and technologies.

Complementing fundamental education with active labour market policies, workforce training and other opportunities for lifelong learning can encourage workers to stay engaged and continue to participate in changing labour markets.

Conclusion: race with – not against – the machine

In the long run, technological innovation can bring about higher incomes and quality of life, including more leisure. This prediction is attainable for the entire population – but only if public institutions promote equality of opportunities, generate an educational system that favours flexible skills and creativity, and use redistribution policies to share the proceeds of technological gains.

With proper public institutions, instead of raging or racing against the machine, we can race with the machines toward a better future.

Further reading

Acemoglu, Daron, and David H Autor (2011) ‘Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings’, Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume 4, edited by Orley Ashenfelter and David E Card, Elsevier.

Acemoglu, Daron, and Pascual Restrepo (2018) ‘The Race between Man and Machine: Implications of Technology for Growth, Factor Shares, and Employment’, American Economic Review 108(6): 1488-1542.

Allen, Robert C (2009) ‘Engels’ Pause: Technical Change, Capital Accumulation, and Inequality in the British Industrial Revolution’, Explorations in Economic History 46(4): 418-35.

Autor, David H (2015) ‘Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 29(3): 3-30.

World Bank (2018) World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work, Washington, DC.

This column summarises ‘The Future of Work: Race with – not against – the Machine’, published by the World Bank Group.