In a nutshell

In recent years, Islamic banks in the UAE have had higher growth rates of lending and deposits, while conventional banks have had a better return on assets and return on equity.

This difference between Islamic and conventional banks’ performance indicates contrasting business models: the former are more geared towards faster growth of the balance sheet, while the latter are more focused on maximising returns.

Enhancing prudential requirements to ensure capital adequacy and adequate reserves will help to foster growth and increase the profitability of the UAE’s banking system.

The performance of the banking system should be assessed by developments on both the assets and liabilities sides of the balance sheet. These developments are very much dependent on the macroeconomic environment.

In oil-producing countries, economic activity is dependent on the oil price cycle, which determines government revenues and spending, and on available international reserves in support of liquidity in the banking system and exchange rate stability.

During an oil price boom, the economy is in strong expansion, supported by high government spending, ample liquidity in the banking system and strong positive sentiment among investors and the private sector. In this environment, the banking sector thrives, capitalising on the supply of liquidity and robust demand for credit, resulting in a rise in the growth of deposits and credit in support of growth of the non-energy sector.

But since the new era of ‘low for long’ oil prices that started in mid-2014, the banking sector in many oil-producing countries has experienced a slowdown in deposits that affected liquidity. This has been coupled with slower demand for credit that has affected credit growth and ultimately the growth of non-energy GDP.

Hence, evaluating the impact of lower oil prices on the capacity and efficiency of the banking sector should be at the heart of diversification strategies of economies that have traditionally been dependent on oil endowments for liquidity, positive investor sentiment, growth and employment.

Effects of the oil price decline on Islamic and conventional banks

While the broad focus of our research is on the capacity of the banking system to weather the implications of the decline in the oil price, we also distinguish between conventional and Islamic banks.

Islamic banks in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have become systemically important and continue to increase their market penetration, outpacing conventional banks’ assets and growth of lending and deposits. As Islamic banks continue to grow in GCC countries, it is worthwhile examining the experience of Islamic banks in coping with the new era of lower oil prices and comparing it with the traditional model of conventional banks.

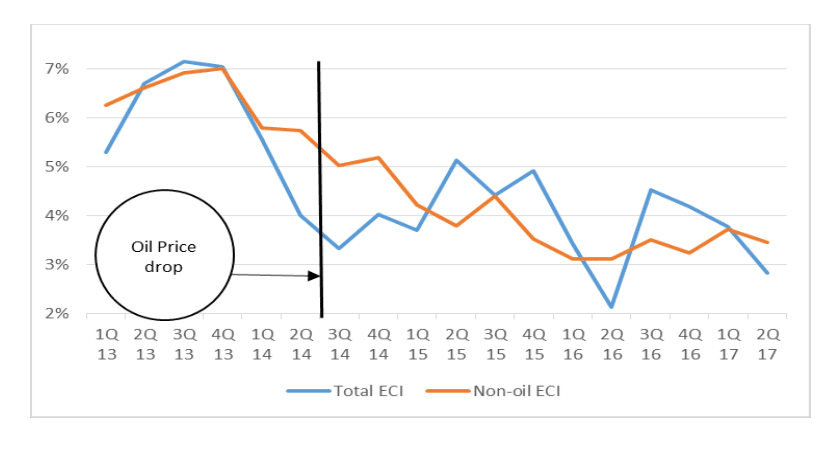

The case of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is of particular interest as the country had annual real non-energy growth of 4.6% at the end of 2014. Following the persistent decline in the oil price, average annual non-energy growth reached 2.9% in 2015/16.

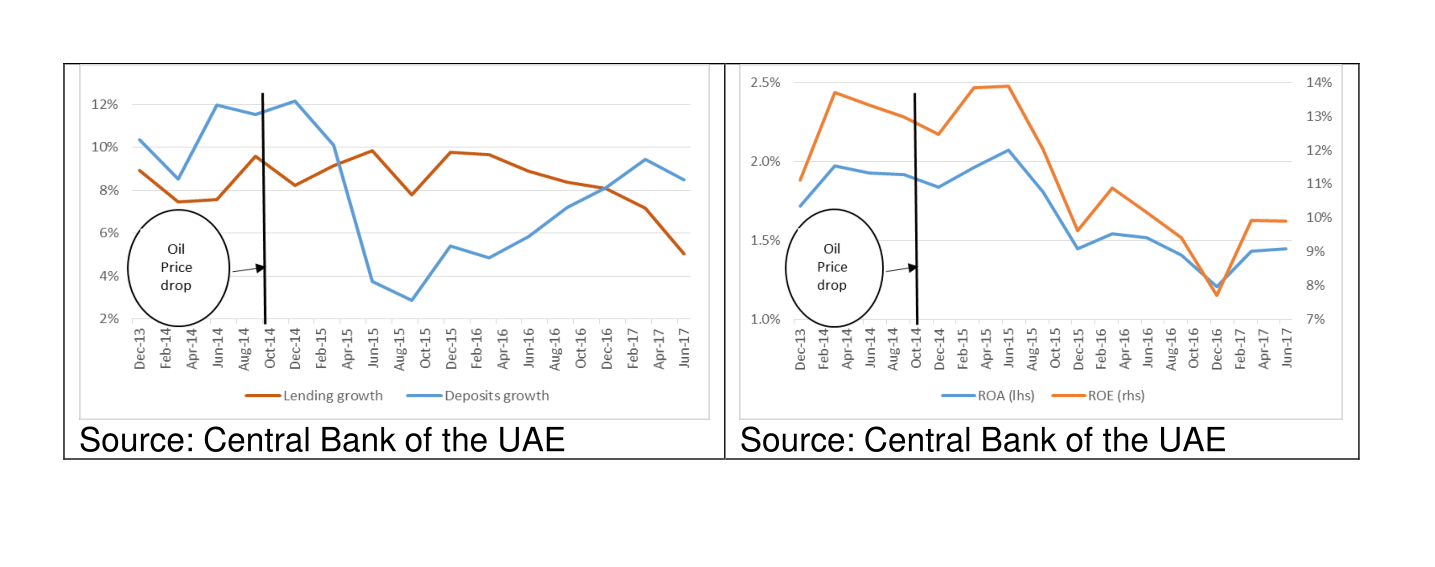

At the same time, banks’ deposits and lending had grown by 11.1% and 8% year-on-year respectively as of December 2014; while on average they grew by 4.9% and 6.9% year-on-year respectively for 2015/16. Lending grew by 15.8% and 5.9% year-on-year for Islamic and conventional banks respectively as of December 2015; while as of June 2017, lending grew by 7.3% and 2% year-on-year respectively.

Clearly, the decline in the oil price has resulted in a decline in liquidity and government spending. The combined effect has had an adverse impact on investor sentiment, slowing down the demand for credit.

While liquidity has improved more recently, supported by the recovery of government deposits against the backdrop of diversifying sources of deficit financing, the initial pace of fiscal consolidation and the recent decline in credit growth have weighed negatively on economic activity, slowing down non-energy growth. The slowdown has been evident across the balance sheets of both conventional and Islamic banks in the UAE.

The UAE’s banks are characterised by relatively high levels of profitability (on average the return on assets and the return on equity were 1.5% and 11.1% respectively in 2016 for all national banks) and healthy levels of credit and deposit growth (6% and 6.2% respectively in 2016).

But is instructive to analyse whether there was a significant negative impact on banks’ performance indicators, credit and deposit growth after the oil price fall from mid-2014, as many sectors of the economy were affected adversely (See Figures 1, 2 and 3).

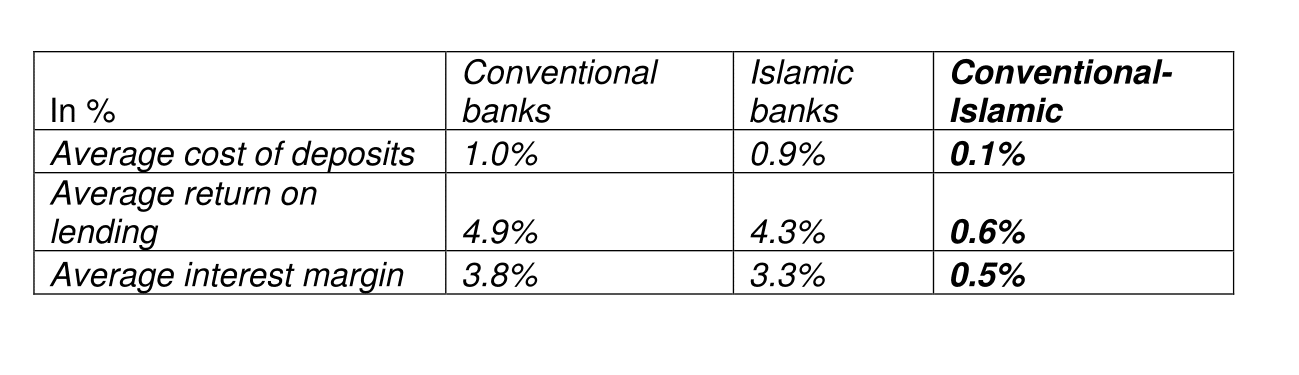

In addition, the interest margin (the difference between interest income and interest expense) for banks has declined, negatively affecting banks’ profitability – by 0.2 percentage points from an average of 4% prior to the oil price decline to an average of 3.8% after the oil price decline. Similarly, for Islamic banks, the profit margin has declined by 0.6 percentage points from an average of 3.9% to an average of 3.3% for the period from the third quarter of 2014 to the second quarter of 2017.

Islamic banks in the UAE have shown very high growth rates of loans and deposits in recent years. As of the second quarter of 2017, credit and deposit growth for Islamic banks were 7.3% and 8.7% respectively, while for conventional banks, they were 2% and 5.8% respectively, indicating a higher pace of growth for Islamic banks.

In addition, the shares of Islamic banks’ credit and deposits have increased from 17.1% and 19.2% of the total as of December 2013 to 22% and 23.6% in June 2017. This illustrates the much faster pace of growth for the two indicators of Islamic banks’ performance.

On average, the interest margin for this period is 3.3% for the Islamic banks, compared with 3.8% for conventional banks (see Table 1).

Banks’ vulnerability and potential policy responses

Our analysis considers the determinants of banks’ performance indicators – such as profitability, lending and deposit growth – drawing a contrast between conventional and Islamic banks. The results establish the dependency of the banking sector on bank-specific indicators and developments in the macroeconomy. Performance has been affected adversely by the decline in the oil price, but it has varied across banks based on the business model, whether Islamic or conventional.

Banks continue to face vulnerability from global spillovers, such as higher US interest rates, lower energy prices and declining growth in trading partners, which have affected the macroeconomic determinants of growth. In particular, evidence indicates the significance of higher US interest rates, the impact of which is transmitted to the UAE banking system via lower loan growth and higher deposit growth. The combined results are lower returns on assets and equity.

Government spending is a major driver of economic conditions, increasing deposit growth and banks’ returns. Monetary growth stimulates loan growth. Furthermore, a pickup in growth in major trading partners has a positive impact on banks’ returns and deposit growth.

Bank-specific indicators affect their performance. Rising non-performing loans decrease returns. An increase in required reserves and capital adequacy increase returns. The growth of high liquid assets decreases loan growth. An increase in capital market funding decreases deposit growth.

These results indicate that banks can hedge against macroeconomic vulnerability and global spillovers by building their own capacity to weather the shocks. Specifically, higher reserves and capital adequacy increase the resiliency of the banking system. Moreover, hedging against non-performing loans and safeguarding indicators of financial soundness foster growth and boost returns.

The evaluation of the difference between Islamic and conventional banks indicates contrasts between the two business models. Islamic banks appear to be more geared towards faster growth of the balance sheet. In contrast, conventional banks are more focused on maximising returns.

From a regulator’s perspective, these results are informative for policy measures that could be instituted by the central bank to solidify the resilience of the banking sector and enhance its efficient intermediation to contribute to non-energy growth and solidify economic diversification. Specifically, enhancing prudential requirements to ensure capital adequacy and adequate reserves will help to foster growth and increase the profitability of the banking system.

Strengthening prudential measures and safeguarding indicators of financial soundness, coupled with an improved outlook for the macroeconomy and the global economy, will position UAE banks to resume growth and increase profitability as they prepare to emerge stronger from the downturn imposed by the ‘low for long’ oil price cycle.

Figure 1. Lending and deposits growth of UAE national banks

Figure 2. Average return on assets and return on equity of UAE national banks

Figure 3:

Overall and non-oil economic growth in the UAE

Source: Central Bank of the UAE

Note: As there is no official quarterly GDP published for the UAE, a proxy index of economic activity (quarterly GDP growth), an Economic Composite Indicator (ECI) has been created by the Central Bank of the UAE.

Table 1:

National banks’ average cost of deposits, income on lending and interest margin by bank type

Source: Central Bank of the UAE