In a nutshell

Trade premia in MENA economies suggest that there are higher barriers to entry for exporting and importing firms than elsewhere, and access to markets and inputs is often distorted.

Export promotion can be effective: there is a need for programmes that support sustained trading output in viable and competitive activities.

MENA economies’ lack of a supporting middle of expanding and growing exporters is more evident than in other regions.

Are traders different? An extensive and diverse body of research indicates that exporting firms tend to be larger and more productive than firms that aren’t involved in international trade (see Hayakawa et al, 2012, for an overview).

Similarly, firms that import intermediate goods also tend to be more productive and employ more people. Importing may allow these firms to access foreign technology, seek higher quality inputs, and provide an entry point for learning about the workings of international markets (Amiti and Konings, 2007).

Researchers have referred to the larger size and productivity of both exporting and importing firms as ‘trade premia’. Yet while these results are consistent across time and geographical regions, the mechanisms that generate these premia are less clear: it may be that larger and more productive firms are the ones that can break into and compete effectively in foreign markets. It also may be that once firms start trading, they gain access to new technology and know-how, allowing them to become more productive and grow – what is known as ‘learning-by-doing’.

Are these relationships the same in MENA?

Our research takes up this question specifically for traders in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Using a unique, firm-level dataset for more than 80 middle-income economies based on enterprise surveys conducted by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Investment Bank and the World Bank, we explore the underlying characteristics of firms that export, import and do both – ‘two-way traders’.

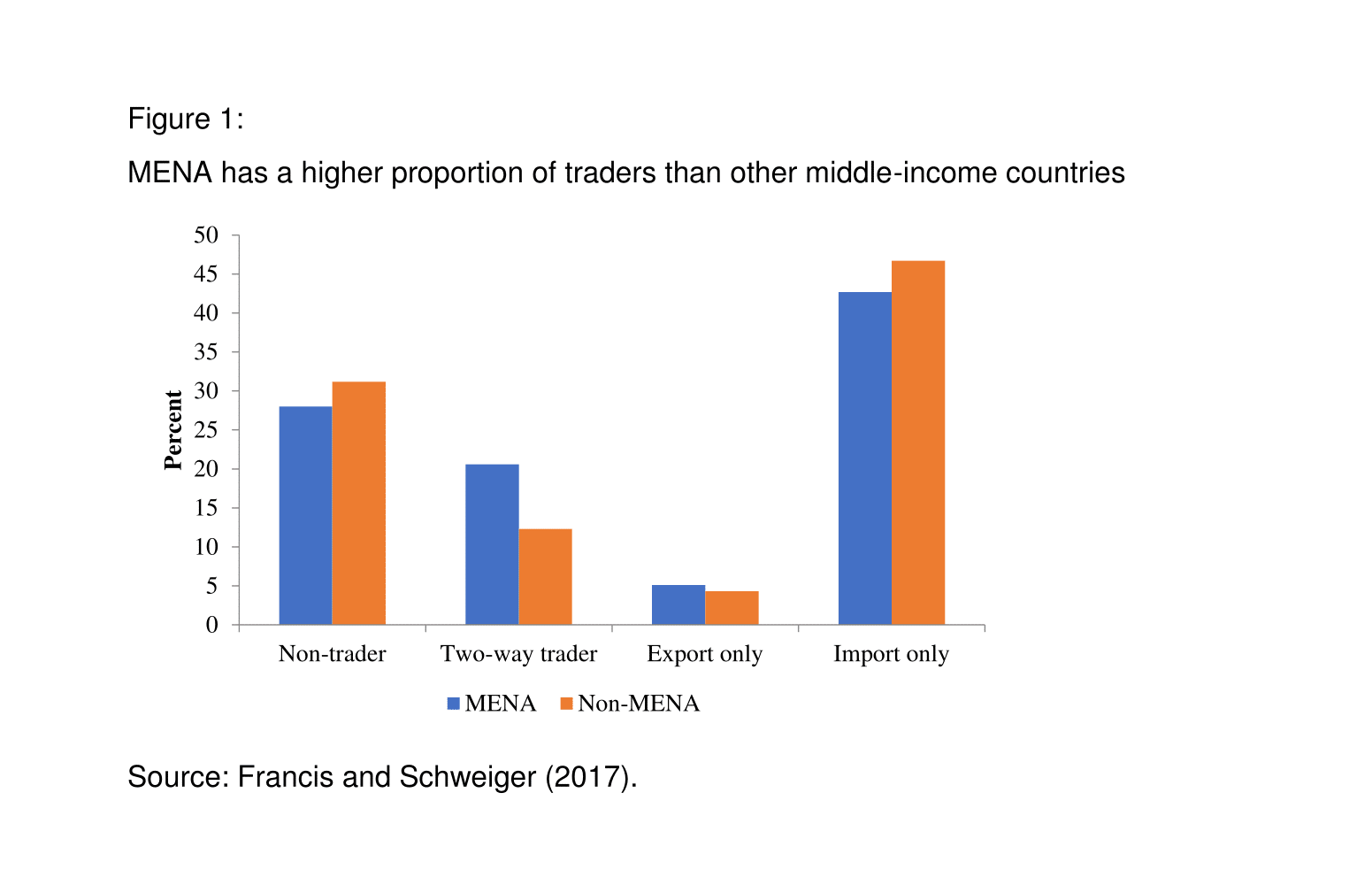

Previous research finds that MENA economies trade at volumes below their potential, especially given the region’s proximity to Europe (Behar and Freund, 2011). Despite this, the region features many trading firms: it’s simply that these firms tend to be low-volume traders. Compared with averages from over 80 similar economies from the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys, MENA has a higher proportion of traders, especially those that both export and import (see Figure 1).

So, are MENA traders also bigger and more productive compared with non-traders? Here, the evidence is mixed. In manufacturing, MENA exporters are larger than firms in the region that don’t export, but this gap is substantially smaller than in other regions. What’s more, MENA exporters in both manufacturing and services are no more productive than those that do not export at all.

The picture changes when we differentiate firms by their export volumes. The three categories are superstars (the top 5% of firms by export value), big players (firms between the median and 94th percentile) and small players (firms below the median).

The MENA region’s superstar manufacturers are seven to nine times the size of non-exporters, while big players are roughly twice the size of non-exporters. Both these findings are in line with the trade premia we find elsewhere in the world.

But the region’s small player manufacturing exporters – the abundant, low-volume exporters – are no larger than non-trading firms. What’s more, these small players actually exhibit lower productivity levels compared with non-exporting manufacturers.

These patterns are similar for the region’s services firms engaged in trading. While the superstar services exporters are indeed larger and more productive, low-volume small player exporters are no larger (indeed, they are even smaller) than non-traders and no more productive.

Our study also looks at manufacturing firms that only export, those that only import intermediate goods and those that engage in both activities. For manufacturers that only import, we find the expected positive and significant trade premia for both size and productivity: these firms are twice as productive on average as those that do not use intermediates from abroad.

Similarly, MENA’s two-way traders are more productive and larger than non-traders, though this size premium is smaller than in other regions.

Next steps for research and policy

While our findings shed some light on the dynamics of trading firms in MENA economies – comparing them with non-traders in the region as well as with traders elsewhere – the results are largely descriptive. But they do raise a few salient questions and policy implications.

First, economic research predicts that firms that begin trading (particularly exporters) will be among the largest, most productive and most promising businesses. Free and open entry to export markets and exposure to international competition will ensure that less efficient firms exit the market, while the survivors continue to grow.

Trade premia in MENA indicate that these forces are not operating properly, suggesting higher barriers to entry for trading firms, and privileged access to markets and inputs. In particular, access to inputs from abroad may be distorted: several countries in the region have overvalued exchange rates, making imports relatively cheaper. But access to foreign currency itself can be limited, which means that only a few firms may leverage imported goods and materials.

Second, a specific area of policy focus and research should be the role of export promotion agencies. MENA features several active agencies for export promotion, including EPCC in Egypt, Jedco in Jordan, IDAL in Lebanon, CEPEX in Tunisia and several others. These agencies have been particularly active in the promotion of small and medium-sized exporters (Jaud and Freund, 2015).

Export promotion can be effective. One study finds that each dinar of support provided by Tunisia’s FAMEX export promotion programme resulted in nine dinars of exported output. Yet after only a few years, these effects disappeared, indicating that there is a need for programmes that support sustained trading output in viable and competitive activities (Cadot et al, 2015, cited in Jaud and Freund, 2015).

Third, our evidence supports previous findings that MENA lacks a supporting middle of expanding and growing exporters. Jaud and Freund (2015) call this dynamic one of champions ‘without a team’. We show that this lack of a team is indeed more evident in MENA than elsewhere.

Further research and policy work should focus on what can be done to help this middle to grow, including removing potential distortions to firms that export, as well as those accessing inputs from abroad.

Further reading

Amiti, M, and J Konings (2007) ‘Trade Liberalization, Intermediate Inputs, and Productivity: Evidence from Indonesia’, American Economic Review 97(5): 1611-38.

Behar, A, and C Freund (2011) ‘The Trade Performance of the Middle East and North Africa’, Middle East and North Africa Working Paper Series No. 53, World Bank.

Cadot, O, AM Fernandes, J Gourdon and A Mattoo (2015) ‘Are the Benefits of Export Support Durable? Evidence from Tunisia’, WPS 6295.

Francis, D, and H Schweiger (2017), ‘Not So Different from Non-traders: Trade Premia in Middle East and North Africa’, Economics of Transition 25: 185-238.

Hayakawa, K, T Machikita and F Kimura (2012), ‘Globalization and Productivity: A Survey of Firm-level Analysis’, Journal of Economic Surveys 26(2): 332-50.

Jaud, M, and C Freund (2015) ‘Champions Wanted: Promoting Exports in the Middle East and North Africa’, Directions in Development, World Bank.