In a nutshell

Personal experiences largely determine whether people continue to support the economic and political institutions that underpin their society.

In terms of satisfaction with their economic situation, only 15% of respondents in the region say that they are living comfortably on their present income.

More than two thirds of people in the region are generally optimistic about their future, with women slightly more optimistic than men.

Since the early days of the Arab Spring in 2010, many Middle Eastern countries have experienced a profound transformation of their economic and political institutions. How has this affected people’s lives and their social, economic and political preferences? Understanding this process is important as personal experiences largely determine whether people continue to support the economic and political institutions that underpin their society.

To monitor people’s perceptions and attitudes, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) publishes assessments for its countries of operation in the South-eastern Mediterranean region (SEMED): Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia. (Lebanon became an EBRD country of operation in mid-2017 and is not part of the most recent assessment round.)

The most recent assessments are based on data from the 2011 and 2015 Gallup World Polls, nationally representative surveys that are conducted every year in over 120 countries. In each country, about 1,000 individuals are asked about a wide range of topics.

The data provide rich information on demographic characteristics (age, gender, educational attainment, marital status and religion) as well as labour market outcomes. The survey also includes sections on attitudes and values, public service delivery and inclusion, among others. Importantly, the Gallup data also make it possible to benchmark the SEMED region vis-à-vis some advanced market economies (France, Germany, Italy, Sweden and the UK) as well as Emerging Europe (the ‘transition region’).

The ‘transition region’ comprises Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan); Central Europe and the Baltic states (Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovak Republic and Slovenia); Eastern Europe and the Caucasus (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine); Russia; South-eastern Europe (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Greece, Kosovo, Montenegro, Romania and Serbia); and Turkey.

The country assessments reveal three core messages about attitudes in the SEMED region:

The ‘happiness gap’ remains substantial

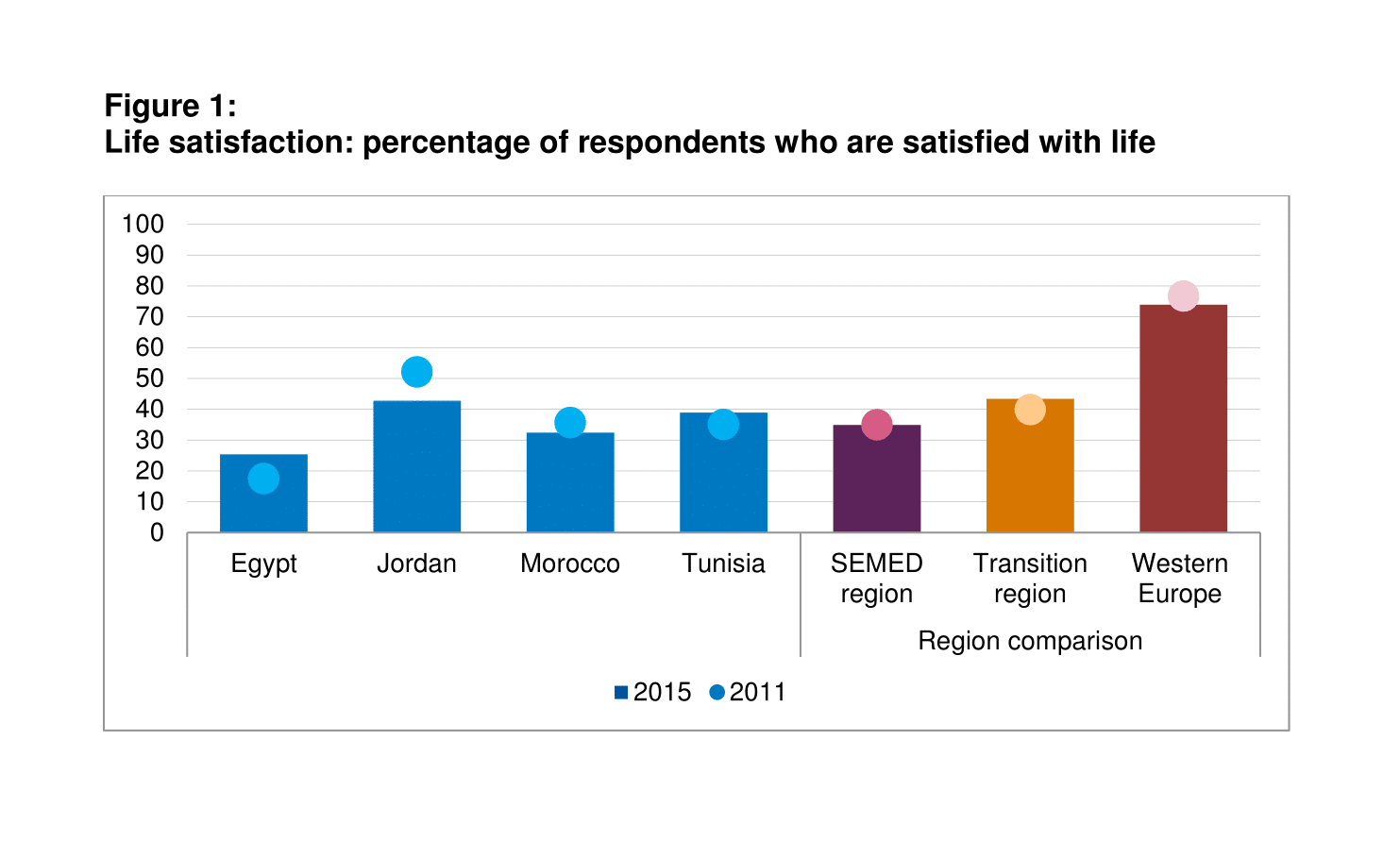

Today, individuals living in the SEMED region report levels of life satisfaction lower than for those who live in the transition region and Western Europe (Figure 1). Egypt (25%) has the lowest share of respondents who are currently satisfied with their life. In sharp contrast, life satisfaction is higher in Jordan (43%) than in any other SEMED country.

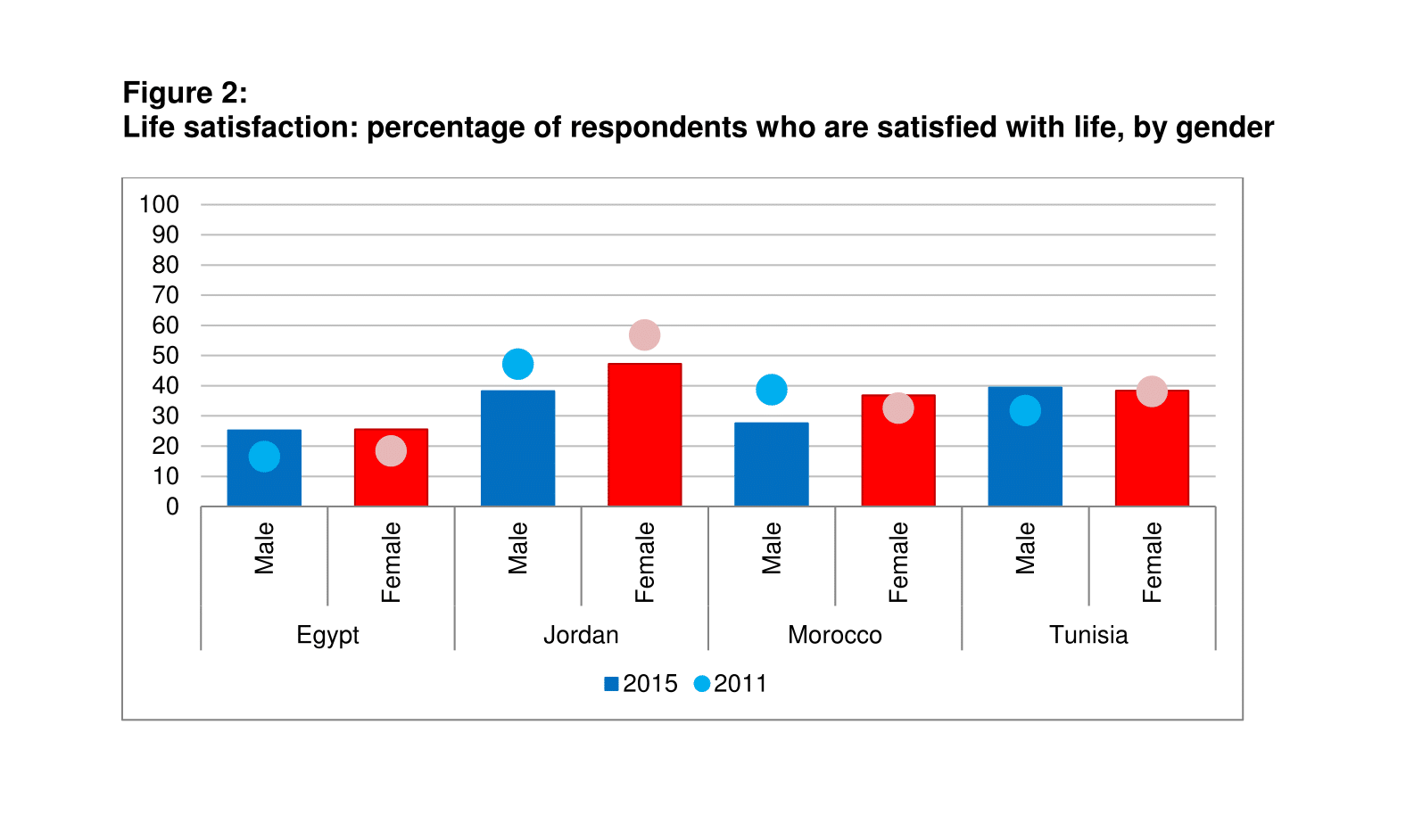

There are also some notable differences with regard to demographic characteristics. For example, Figure 2 shows that women have considerably higher levels of life satisfaction in Jordan and Morocco. When it comes to satisfaction with the economic situation, only 15% of respondents in the SEMED region state that they are living comfortably on their present income. The corresponding proportions are 17% in the transition region and 36% in Western Europe.

People are optimistic about the future

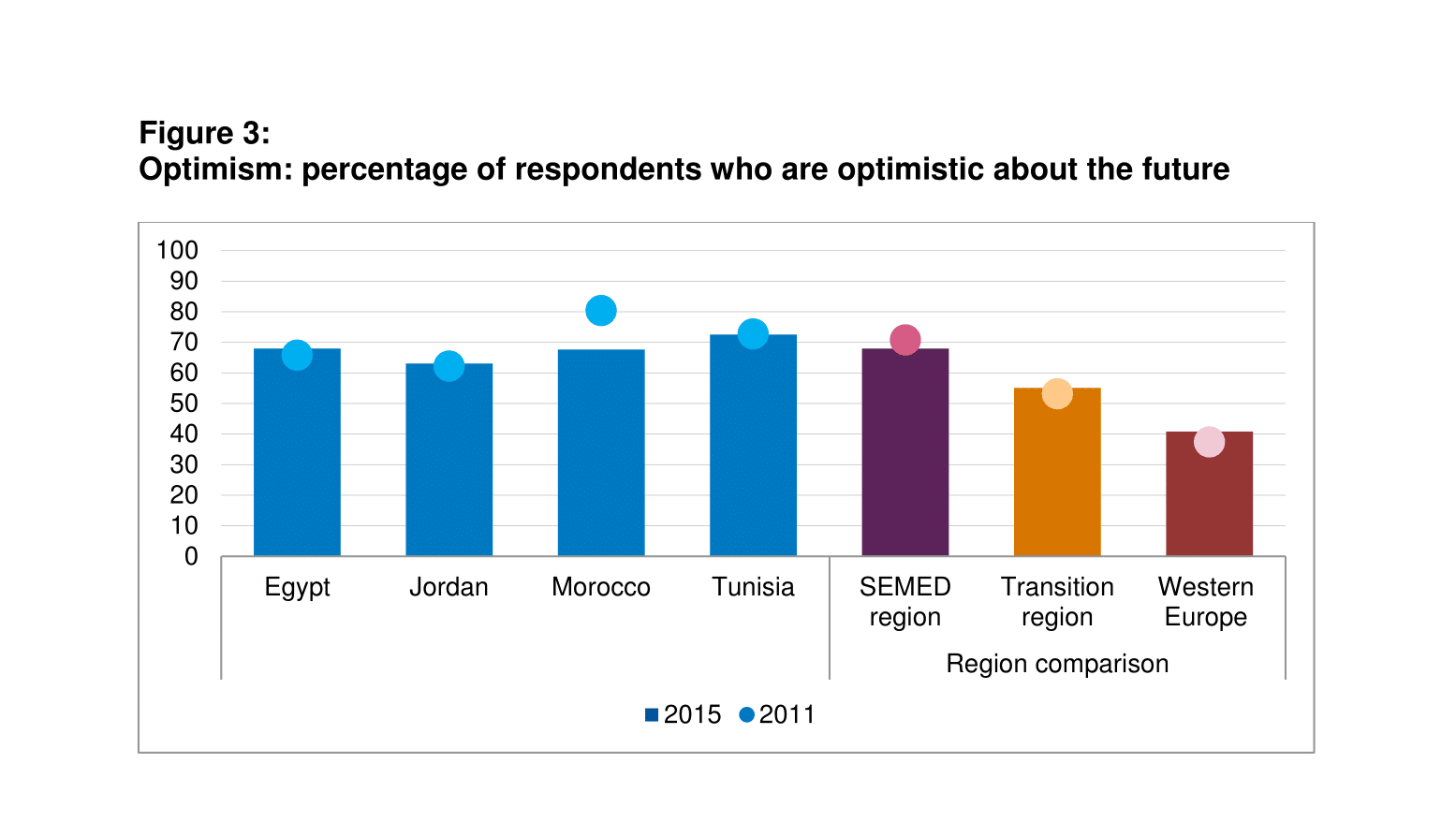

On the bright side, people in the SEMED region are generally optimistic about their future (68% – Figure 3). This figure is higher than in the transition region (55%) and Western Europe (41%).

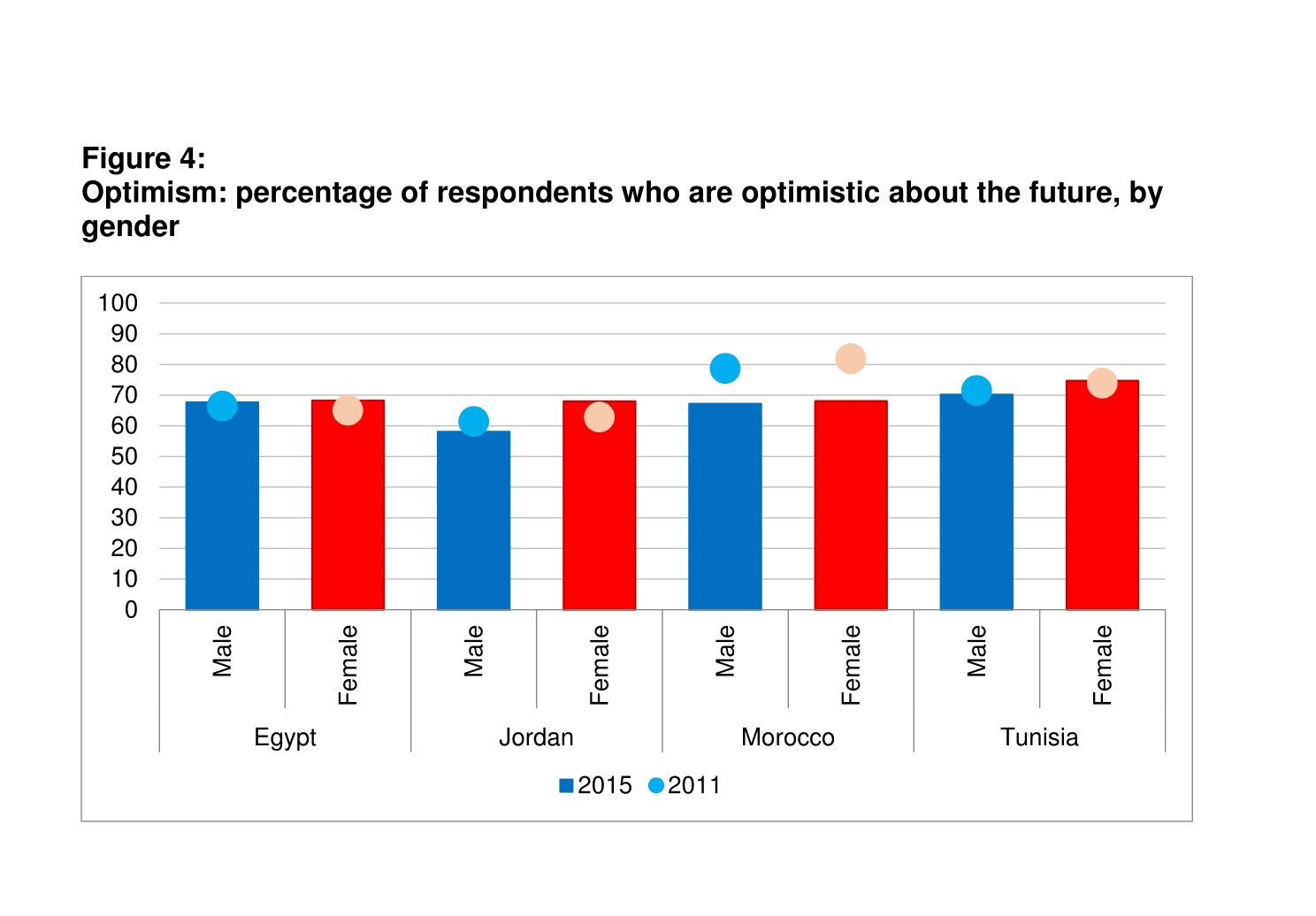

Moreover, women are slightly more optimistic than men in all SEMED countries (Figure 4). Additional analysis of the Gallup data shows that on average, older and poorer individuals tend to report lower levels of life satisfaction. These groups are also less optimistic about the future and this holds across the entire region.

A majority report that their physical health is good

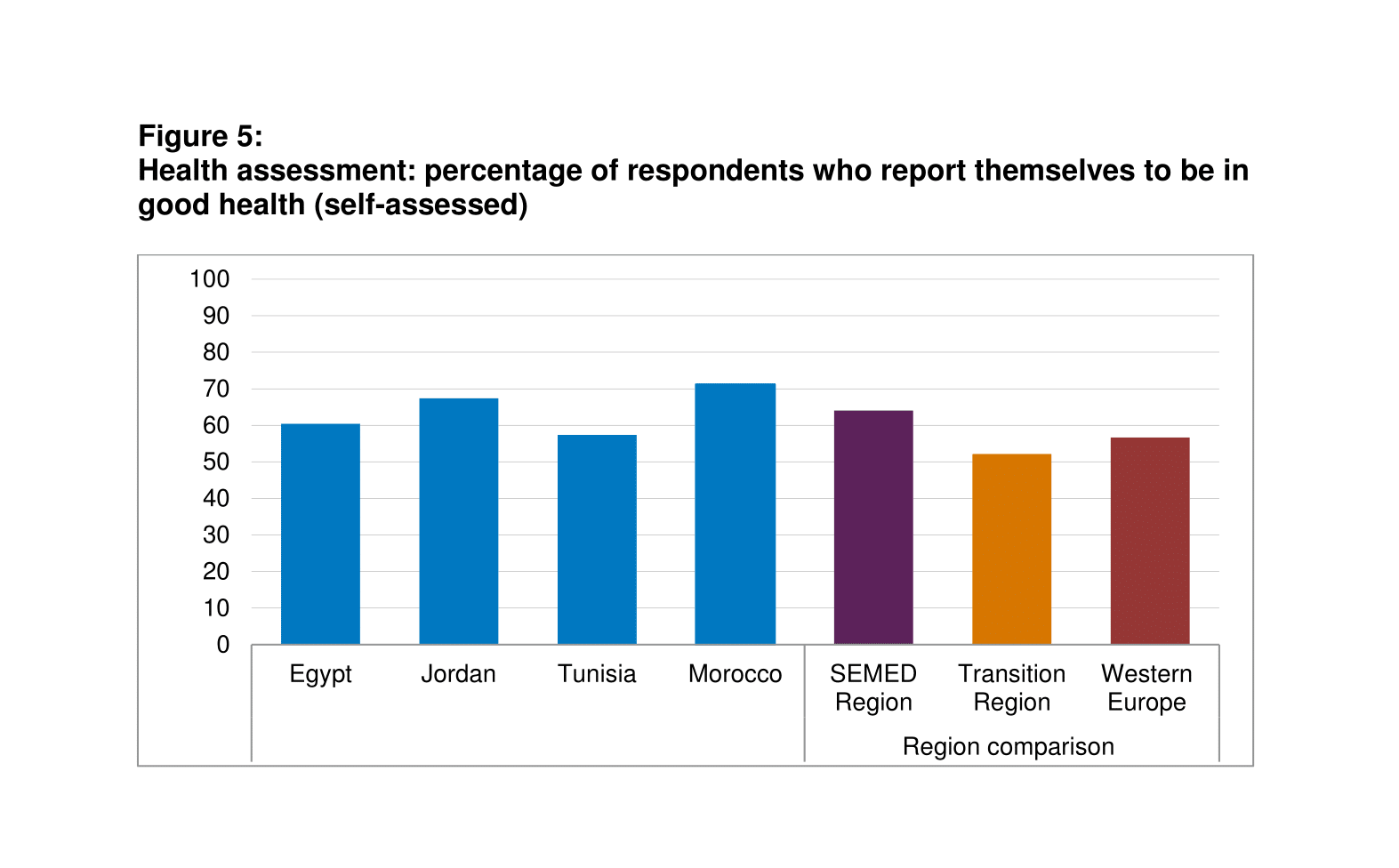

In the SEMED region, 64% of respondents agree or strongly agree that their physical health is very good (Figure 5). This figure is higher than the averages for the transition region (52%) and Western Europe (57%).

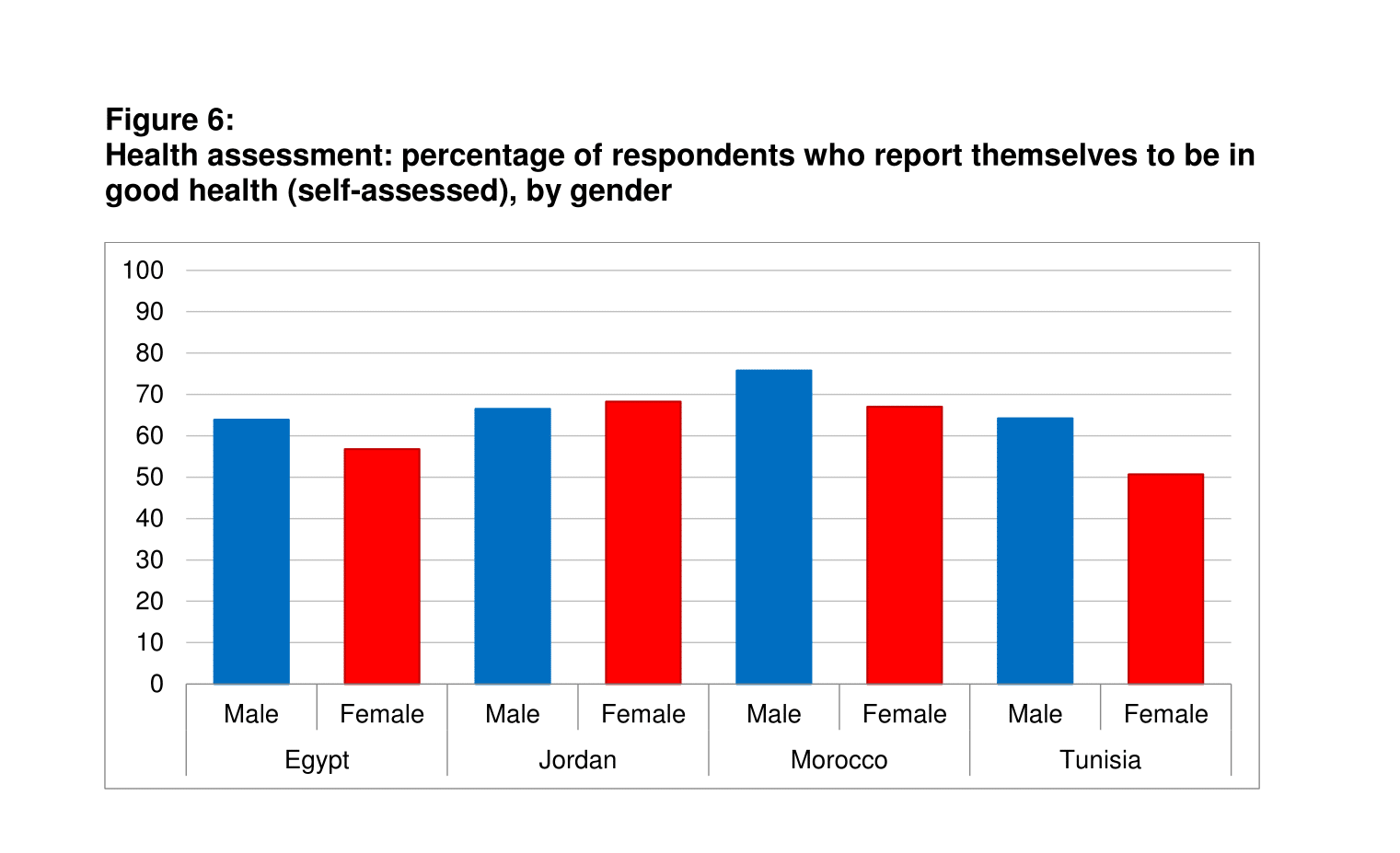

Perhaps not surprisingly, across the entire region, younger and richer individuals are more likely to report being in good health than their counterparts in the lower and middle-income brackets. In addition, men report being somewhat healthier than women in the SEMED countries, except for Jordan (Figure 6).

Further reading

EBRD (2017) ‘Life in Transition: A Decade of Measuring Transition’.