In a nutshell

Egypt provides an illustration of how trade liberalisation and crony capitalism can go hand in hand.

Economic reform is typically brokered by political insiders in a manner that neutralises its effect on connected business elites.

As tariffs fell in Mubarak-era Egypt, sectors where political cronies operated were compensated through greater non-tariff protection – with the result that non-tariff measures contribute more to overall trade restrictiveness than tariffs.

Selective trade liberalisation has been a pervasive feature of economic reforms supported by multilateral institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. As many developing countries have sought to liberalise their trade, they have done so in a highly selective fashion, eliminating trade protection in some sectors while maintaining it in others.

Such episodes of selective economic reform in Africa inspired political scientist Nicolas van der Walle to coin the term ‘partial reform syndrome’. Our research provides one of the first empirical illustrations of this in the arena of trade policy (Eibl and Malik, 2016).

Several North African countries made serious efforts to reform their trade structures in the 1990s. Such reforms predominantly focused on tariff reductions, and were usually preceded by the proliferation of preferential trade agreements.

Overall, the region responded to such pressures for tariff reductions by lowering tariffs at a higher rate than any other part of the world. But trade liberalisation was selectively pursued, since the generalised decline in tariffs was counterbalanced by growing reliance on non-tariff measures (NTMs), which tend to be more opaque and discretionary.

We argue that political economy factors provide an important explanation for such selective trade reform. Focusing on Mubarak-era Egypt, we empirically examine how the presence of politically connected businesses – ‘cronies’ – influenced trade policy in Egypt during the decade of 2000s.

Compiling a unique database on political connections and mapping them across products and sectors, we show that sectors with a greater concentration of cronies enjoyed systematically higher levels of non-tariff protection.

Data and research design

We carry out our empirical analysis using several novel and original datasets. First, we extract information on the nature and introduction of NTMs over time from the WITS database on NTMs at the six-digit product level (World Bank, 2013). Aggregating the product-level information at the four-digit sector level, we construct several variables capturing the incidence and intensity of NTM protection.

We combine this with a unique dataset on politically connected businesses in Egypt, comprising details of Egypt’s core business elite provided by Roll (2010) and information from the Orbis database on the list of shareholders and co-investors.

Second, we assess whether the entrepreneurs on this extended list were politically connected. We consider a spectrum of political connections, including shareholders or top officers of the company enjoying a direct political connection, such as holding political office or membership of parliament or the National Democratic Party. We also consider individuals with business or personal ties to the Mubarak family.

Third, having identified connected companies, we compile a list of products that they manufacture and their dates of establishment using a variety of data sources, including company websites, press archives and the Orbis database.

Finally, we allocate each product to its respective sector, using the most detailed four-digit International Standard Industrial Classification. An advantage of this database is that we can track the entry of politically connected enterprises over time, which is helpful in identifying the impact of cronyism on trade protection.

Overall, about 57% of the total manufacturing sub-sectors are exposed to political cronies in our sample, and this sectoral exposure to cronyism doubled after 1995. There is also considerable variation in NTM coverage: the share of products covered by an NTM ranges from 19% to 100%.

Using variation in the application of non-tariff barriers across sectors and over time, we ask:

• Is the transition of a sector from being ‘non-crony’ to ‘crony’ systematically associated with higher incidence and intensity of NTMs?

• Does the likelihood of NTM protection increase significantly in sectors where cronies enter for the first time?

• Is the presence of cronies systematically associated with the higher prevalence (or density) of NTMs?

In each case, our main focus is on determinants of within-sector variation in the application of NTMs over time. To establish causality, we explore exogenous shifts in trade policy triggered by Egypt’s trade agreement with the European Union (EU) in 2004 – which, we argue, was mainly determined by high-level geopolitics.

The EU agreement resulted in the most far-reaching reforms of the tariff structure. But the tariff reduction was followed by a compensatory wave of NTM protection in the following year. This was a nearly universal shock: 75% of all sectors that witnessed a tariff cut in 2004 faced a rise in NTMs in 2005.

We make use of this important trade policy shift to explore whether sectors with prior exposure to cronies witnessed systematically higher levels of non-tariff protection after the EU agreement.

Key findings and implications

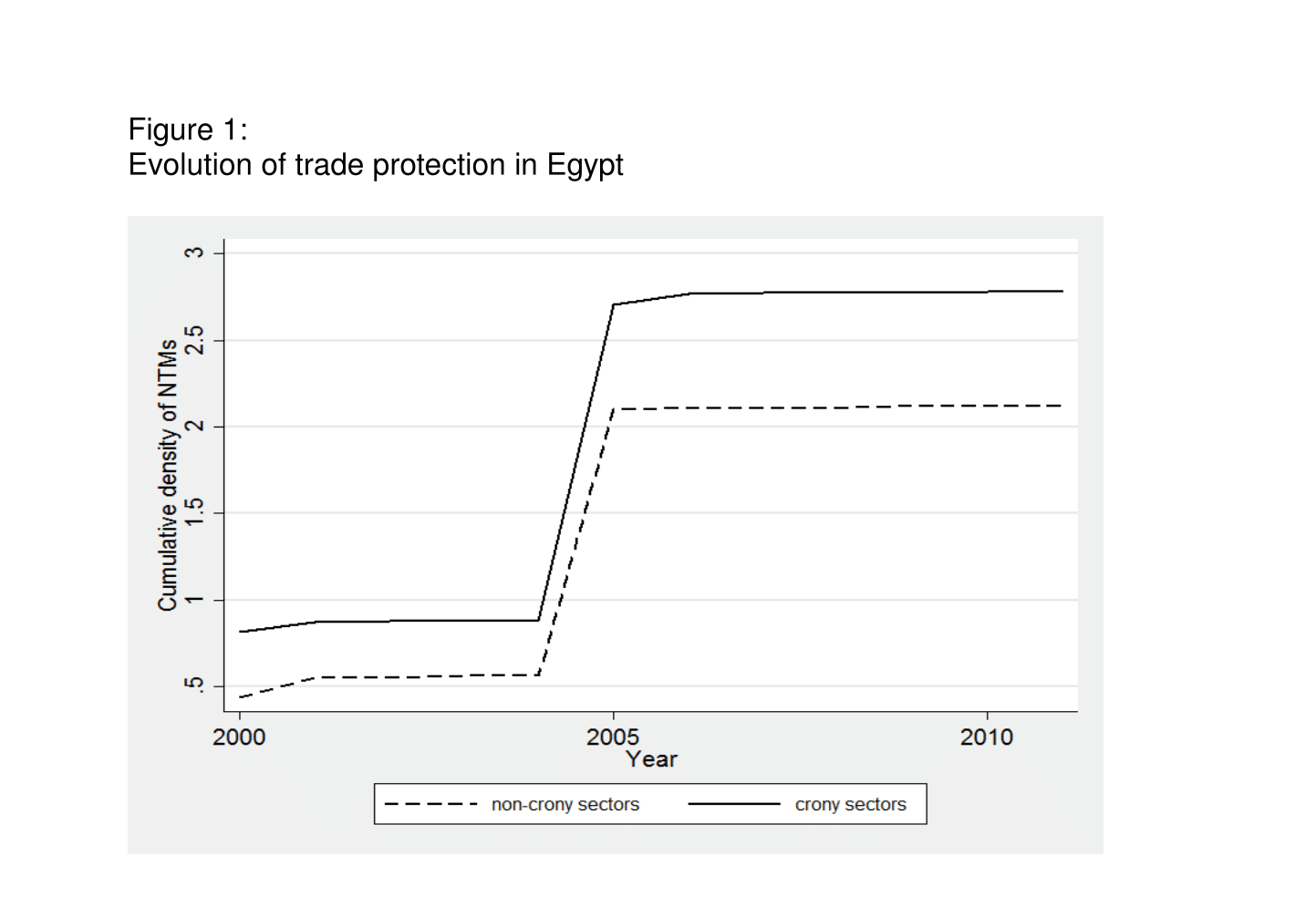

The empirical analysis confirms that politically connected sectors systematically enjoyed higher non-tariff protection, especially in the wake of tariff liberalisation in 2000s. We show that sectors with crony presence are 50% more likely to experience the introduction of NTMs than a non-crony sector.

Furthermore, we empirically demonstrate that although most manufacturing sub-sectors witnessed an increase in NTMs after the EU trade agreement, politically connected sectors were afforded greater trade protection. Specifically, sectors with prior exposure to political cronies received roughly 30% higher compensation in the form of NTMs.

This is supported by Figure 1, which tracks the evolution of NTMs for crony and non-crony sectors. Crony sectors are defined as sectors exposed to crony presence by 1990, 14 years before the EU agreement came into force.

Our evidence has important implications for continuing debates on globalisation and crony capitalism. Egypt provides an important illustration of how trade liberalisation and crony capitalism can go hand in hand.

Emphasising the political foundations of trade policy, we show that economic reform is typically brokered by political insiders in a manner that neutralises its effect for connected business elites. As tariffs fell, sectors where political cronies operated were compensated through greater non-tariff protection.

In some cases, NTMs not only neutralised the effect of trade liberalisation, but they also helped to generate additional rents. In at least 55% of all tariff lines subjected to NTMs in Egypt, the ‘ad valorem’ equivalents of NTMs exceeded the pre-liberalisation tariffs. The resulting rents can serve an important political function, providing binding elite commitments of continued support for the regime.

Our study adds to the slim body of research on the determinants of non-tariff measures, which constitute more than 70% of global trade protection and remain more pervasive in the Middle East than in the rest of the world.

Egypt is one of those countries where non-tariff measures contribute more to overall trade restrictiveness than tariffs. A better understanding of the drivers of non-tariff protection is therefore critical for a trade policy that supports both private sector development and economic growth.

Further reading

Eibl, Ferdinand, and Adeel Malik (2016) ‘The Politics of Partial Liberalization: Cronyism and Non-Tariff Protection in Mubarak’s Egypt’, Centre for the Study of African Economies Working Paper WPS/2016/27.

Roll, Stephan (2013) ‘Ägyptens Unternehmerelite nach Mubarak: Machtvoller Akteur

zwischen Militär und Muslimbruderschaft’, Stiftung Wissenschaft und

Politik, Berlin.

World Bank (2013) ‘World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS)’.