In a nutshell

Should MENA economies decide to implement fiscal rules – and should they be properly designed – the beneficial results would accrue only in the medium to long run.

The effectiveness of fiscal rules is independent of economic size, which suggests that the benefits can be reaped by any MENA country.

Other fiscal institutions play an important role in reducing pro-cyclicality, including modernising tax structures and implementing sovereign wealth funds.

Fiscal policy is pro-cyclical when government spending increases (decreases) in good (bad) times, thus amplifying business cycles. In most advanced economies, fiscal instruments have been designed to operate counter-cyclically, thus reducing the adverse welfare effects of business cycles, such as unemployment and fluctuations in household incomes.

If fiscal policy is working properly, it should expand during downturns and contract during booms. Indeed, the evidence on industrial countries confirms this pattern. In contrast, protracted pro-cyclicality has been documented for developing countries in Latin America (Gavin and Perotti, 1997), Africa (Konuki and Villafuerte, 2016) and the countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region (Abdih et al, 2009).

Counter-cyclical fiscal policy operates on both the revenue and expenditure sides:

On the revenue side, the tax system ought to serve as an automatic stabiliser of the business cycle, reducing aggregate demand pressures whenever private sector activity expands beyond sustainable limits. Ad valorem taxes on goods and services and progressive income taxes perform this function automatically, while profits and dividends of state-owned enterprises can be managed by authorities to avoid fuelling an already expansionary period.

On the expenditure side, counter-cyclical discretionary spending smoothes government spending and thereby aggregate demand.

The evidence indicates that emerging economies have failed to articulate counter-cyclical fiscal policies. Two main explanations have been put forward for this failure:

- The first explanation focuses on limited access to international capital markets during bad times, which stifles the ability of policy-makers to conduct counter-cyclical policies (Riascos and Vegh, 2003).

- The second explanation rests on a political economy argument: during good times, political pressures or complacency that such times will continue for a long time can lead to fiscal profligacy, particularly through public investment projects and transfers to consumers and firms (Tornell and Lane, 1999).

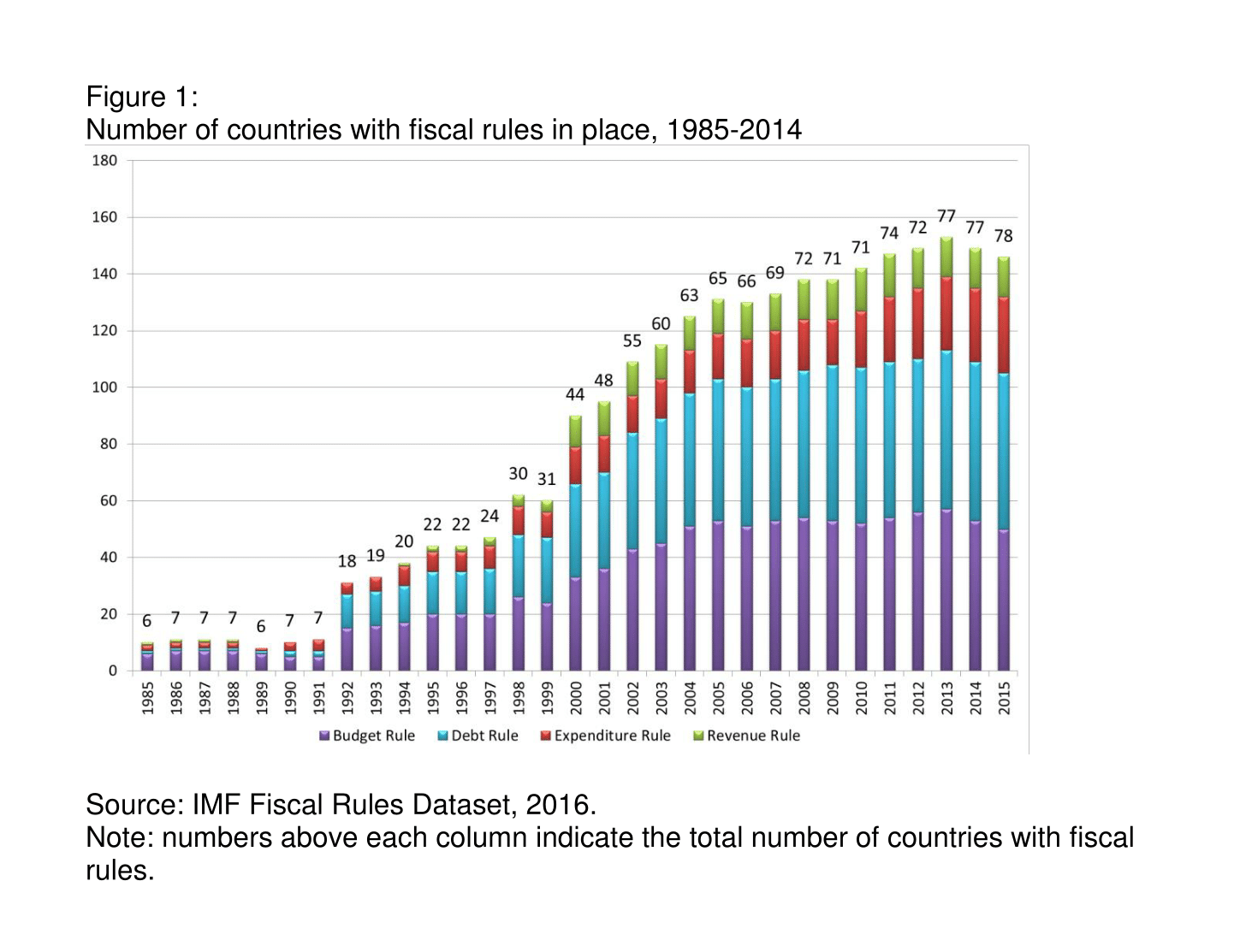

The implication is that additional institutions are needed to discipline fiscal management. Fiscal rules that govern the conduct of fiscal policy offer such discipline and have been in place in a small number of industrial countries for a long time. But it is only since the 1990s that adoption of fiscal rules started spreading worldwide, as part of significant reforms of fiscal frameworks in emerging market economies (see Figure 1).

Adoption of fiscal rules has been motivated by several (often complementary) objectives:

- making fiscal policy design and execution more resilient to political-economy problems that cause deficit bias;

- strengthening fiscal solvency and sustainability;

- contributing to macroeconomic stabilisation;

- and improving intergenerational fairness (IMF, 2013).

There are four general types of fiscal rules: on budget balance; government expenditure; government revenue; and government debt. Debt and budget balance rules (particularly when defined as debt or deficit ceilings) aim at achieving fiscal sustainability. Expenditure and revenue rules aim at macroeconomic stabilisation.

Our research explores the effectiveness of fiscal rules in reducing pro-cyclicality (Schmidt-Hebbel and Soto, 2017). We focus on whether rules promote good fiscal performance and if the type of fiscal rule matters for its impact on fiscal performance.

Our empirical approach is based on the comparative experience of around 120 economies in the period 1985-2015. Using a novel empirical approach, we are able to measure the impact of fiscal rules controlling for other fiscal institutions (such as sovereign wealth funds), political institutions, macroeconomic regimes, development conditions and short-term cycles.

Our study solves the econometric problems resulting from the three defining characteristics of fiscal pro-cyclicality: high persistence; unobserved country heterogeneity; and potential reverse causation and endogeneity, since governments may decide to implement rules as a result of pro-cyclicality.

Several conclusions arise from the empirical evidence:

First, there is significant inertia in fiscal balances and, therefore, the impact of fiscal rules takes a long time to materialise. Should MENA economies decide to implement fiscal rules – and should these rules be properly designed – the beneficial results would accrue only in the medium to long run.

Second, while fiscal rules are important to improve the fiscal stance of an economy, other variables can be as important determinants of fiscal performance. These include a properly designed and functioning system of checks and balances on the government; acceptable levels of political stability; integration with globalised financial markets; and low and stable levels of inflation – all of which can be of particular importance for MENA economies.

Third, other fiscal institutions play an important role in reducing pro-cyclicality, including modernising tax structures to reduce the instability of government revenues and implementing sovereign wealth funds.

The evidence indicates that expenditure rules achieve their intended purpose – that is, they systematically reduce expenditure pro-cyclicality in a country by around 40% on average. This is a significant improvement for any economy. Other rules achieve their intended target too: debt rules lower debt levels and budget balance rules reduce fiscal deficits.

But rules can also have beneficial impacts beyond their primary target. We find that expenditure rules also help to limit the expansion of the government debt and lower deficits, thus improving fiscal sustainability. Our results indicate that the effectiveness of fiscal rules is independent of economic size, which suggests that benefits can be reaped by any MENA country.

Further reading

Abdih, Yasser, Ralph Chami, Michael Gapen and Amine Mati (2009) ‘Fiscal Sustainability in Remittance-Dependent Economies’, IMF Working Paper WP/09/190.

Gavin Michael, and Roberto Perotti (1997) ‘Fiscal Policy in Latin America’, in NBER Macroeconomics Annual 12 edited by Ben Bernanke and Julio Rotemberg, MIT Press.

IMF (2013) ‘The Functions and Impact of Fiscal Councils’, International Monetary Fund Policy Paper.

Konuki, Tetsuya, and Mauricio Villafuerte (2016) ‘Cyclical Behavior of Fiscal Policy among Sub-Saharan African Countries’, International Monetary Fund.

Riascos, Alvaro, and Carlos Vegh (2004) ‘Procyclical Fiscal Policy in Developing Countries: The Role of Capital Market Imperfections’, University of California at Los Angeles, manuscript.

Schmidt-Hebbel, Klaus, and Raimundo Soto (2017) ‘Fiscal Rules and Fiscal Performance: World Evidence’, mimeo, Instituto de Economía, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Tornell, Aaron, and Philip Lane (1999) ‘The Voracity Effect’, American Economic Review 89: 22-46.