In a nutshell

While consumer boycotts are certainly disruptive for bilateral trade, their effect on the boycotted countries’ total exports is quite small.

Most industrialised countries export mainly intermediate and capital goods, for which consumer boycotts work less well.

Given the temporary effect of trade boycotts, cultural conflicts are very unlikely to change international trade relations significantly.

Trade boycotts have a long history. Not long ago, there were boycott calls against French products in the United States following disagreement about the Iraq question, which led to the infamous renaming of French fries as ‘freedom fries’.

The availability of the internet throughout the world has allowed consumers to coordinate grassroots boycotts of this kind that are not dependent on government intervention. So in the age of globalisation, it is important to understand the impact of consumer reaction to international conflicts. But previous economic research finds little conclusive evidence on whether boycotts are effective in the long term or only temporarily, who are the main drivers behind them and which goods are affected.

To answer these questions, my research makes use of two events that act as natural experiments and allow me to identify the effect of consumer boycotts on international trade relations.

In September 2005, a Danish newspaper published a series of cartoons depicting the Islamic prophet Muhammad in an unfavourable manner – the most controversial one showing him with a bomb in his turban. This caused a huge outcry in the Muslim world and violent protests followed. After the Danish government refused to apologise for the cartoons, Muslim religious leaders called for a consumer boycott of Danish goods.

The second case involves Asia’s two biggest economies: China and Japan. In the summer of 2012, a long-lasting territorial conflict about some islets in the East China Sea escalated when the Japanese government announced a plan to nationalise them. Furious protests broke out in China and a consumer boycott was staged against Japanese products.

My study analyses monthly export data for Denmark and Japan around the consumer boycotts. The quality of the datasets makes it possible for me to identify different products on a very fine level. For example, I am able to trace back the value of specific products such as cameras or certain types of cheese.

Since trade flows are subject to considerate seasonal fluctuations, the main difficulty is constructing a counterfactual. To do so, I use the synthetic control group approach: this compares the trade flows to the boycotting country with a weighted average of the flows to other countries where the weighted average resembles the boycotter closely in the period before the events broke out.

The empirical results for the two very different case studies show some remarkable similarities. At first, the effect on bilateral trade relations is U-shaped. The boycott reduces imports little in the first months, then takes off, but finally dies out after a year or two. This suggests that it takes time for boycotts actually to alter trade patterns and that any effects are temporary.

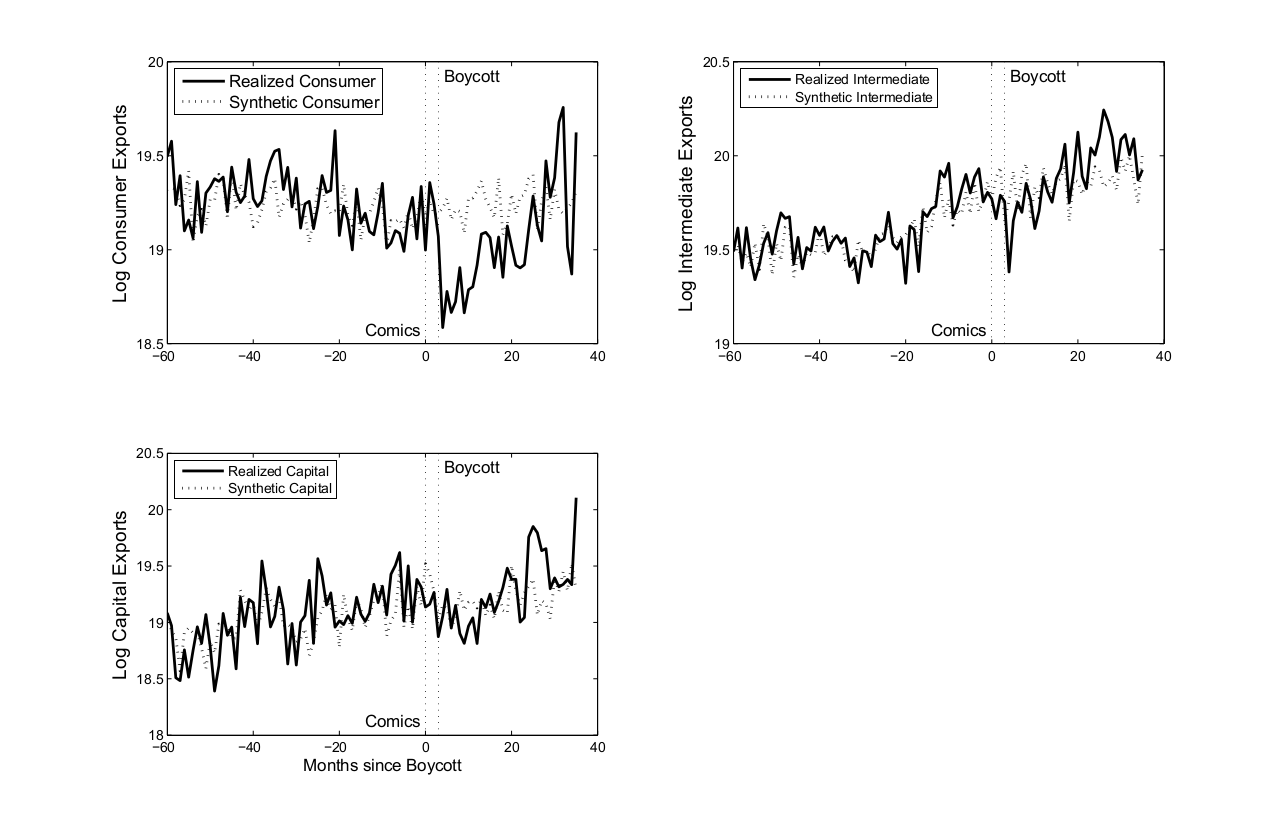

Furthermore, in both boycotts, consumer goods drop much more than intermediate or capital goods, which is a clear indication that the boycotts are mainly carried out by consumers and not firms (see Figure 1).

The effect is particularly strong for highly branded signature consumer goods. For example in the case of Japan, passenger car exports to China dropped by a massive 31.8%. It is perhaps not surprising that firms that rely on foreign inputs are less willing to participate.

Further cross-country analysis shows that countries with higher press freedom boycott more, which suggests that consumer boycotts rely on the ability of consumers to communicate and coordinate their actions.

What are the lessons we can learn from these boycotts and their effects? Should we be afraid of boycotts and avoid cultural conflicts so as to protect exports? While the cases in my study are certainly unique and cannot easily be generalised, a few patterns emerge that can be applied more broadly.

First, while trade boycotts are certainly disruptive for bilateral trade, their effect on the boycotted countries’ total exports is small, in these cases amounting to only 0.4% for Denmark and 0.5% for Japan. Both countries have a broad export base and a single export partner only takes up a small percentage of overall trade. The same is true for the United States and most European countries with a highly diversified base of export partners.

Second, like most industrialised countries, Denmark and Japan export mainly intermediate and capital goods for which consumer boycotts work less well. Given the temporary effect of trade boycotts, cultural conflicts are very unlikely to change international trade relations significantly.

Further reading

Heilmann, Kilian (2016) ‘Does Political Conflict Hurt Trade? Evidence from Consumer Boycotts’, Journal of International Economics 99: 179-91.

Danish exports to the Muslim world by product type