In a nutshell

Building an institutional process for economic policy management and coordination in MENA countries is essential to improve policy consistency and effectiveness.

Key elements include a dedicated, multilayered organisational structure and a cadre of professionals within policy institutions to support leaders and principals.

Revamping communications with different public spheres is key to promoting inclusiveness, transparency and policy predictability.

Economic policy management around the world is becoming more complex. Policy-makers must deal with increasing uncertainties, a complex (and sometimes polarised) political landscape, changing socio-economic priorities and challenges, and increasing interconnectedness in a highly globalised world. In their efforts to develop sound and coherent economic policies, policy-makers must also assess near-term risks and benefits, and consider the socio-economic and political effects over time.

To do this, governments must adopt strong and transparent institutional frameworks that are focused on policies not short-sighted procedures. Policies should be designed within robust management frameworks that have clear objectives and instruments aimed at sustainable and equitable economic growth, which should be communicated regularly.

Gaspar et al (2016) outline a comprehensive, consistent and coordinated approach to policy-making. According to their analysis, consistent policy frameworks anchor long-term expectations while allowing decisive short- to medium-term accommodation whenever necessary. This is achieved by systematically linking instruments to policy objectives over time. Policy consistency assists policy effectiveness.

Putting this in a MENA context requires reforming the framework for economic policy management. In many countries in the region, while the economic decision-making process may have sound constitutional and administrative bases, it has been hampered by institutional shortcomings in formulation, coordination, monitoring and communication.

The main institutional weaknesses include:

- the concentration of power, which places significant managerial and operational responsibilities on policy-makers;

- the tradition of large governments and cabinets;

- the lack of standardised organisational frameworks across ministries;

- the complexity and, in many instances, contradictory nature of legislative acts;

- systemic gaps in public human resources management;

- lack of reliable data and information for policy-makers;

- and the lack of standardised systems of communication.

Improving the framework for economic policy management in MENA countries will depend largely on implementing comprehensive institutional changes to help bridge existing gaps in the policy-making process. Economic policy management covers all policy-making and implementation phases, including:

- setting strategic policy targets and programmes;

- monitoring implementation;

- proposing and pursuing corrective actions;

- managing vertical inter-organisational and horizontal cross-institutional coordination;

- overseeing organisational reforms and development efforts;

- and managing policy deliberations and communication with the public.

There are six thematic areas that need to be addressed to overcome institutional shortcomings, and help to create consistent frameworks that would improve both the credibility and effectiveness of economic policy management in MENA countries, particularly those that have experienced political transitions.

Institutional inclusivity

The reforms should aim to promote effective participation of public institutions involved in the economic policy management process within the executive branch. This can be described as prescribing harmonised inter-organisational (vertical) and cross-institutional (horizontal) connectedness of people and entities.

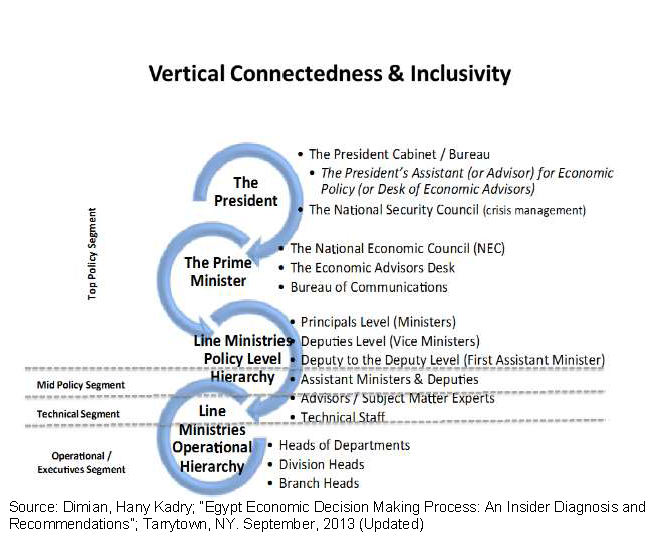

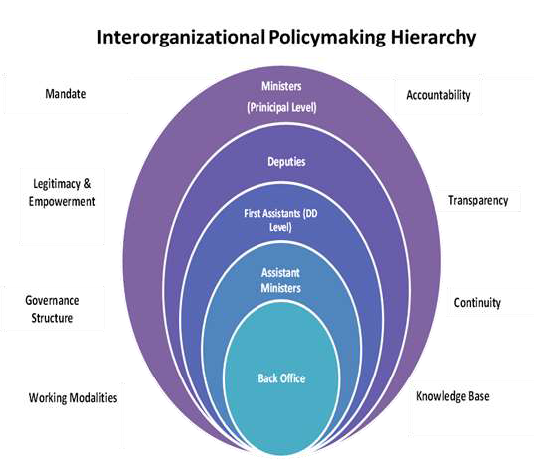

The two diagrams below outline the concept of inter-organisational and cross-institutional (vertical and horizontal) inclusivity and harmonisation. They illustrate multilayered participation in the policy-making process and organisational parallelism at the policy level.

The left-hand figure is a simple illustration of vertical inclusivity, connecting the different administrative levels managing policy-making and implementation. Establishing connectedness for the top policy segment can be achieved through an institutionalised central platform for policy management and coordination.

The right-hand figure is an example of a harmonised organisational structure – a broad outline of the proposed organisational hierarchy in a policy-making platform. It could be replicated across ministries to achieve the organisational parallelism needed for better policy coordination.

A well-structured organisational framework for policy management

This refers to establishing a dedicated, multilayered organisational structure and a cadre of professionals within policy institutions to support leaders and principals (presidents, prime ministers, ministers, governors, heads of public authorities, etc.). This framework should supplement the current operations cadre in terms of mandate, governance and management.

Organisational parallelism

This refers to building a harmonised organisational framework across institutions, which is essential for advancing policy coordination.

Policy coherence and continuity

This refers to establishing an institutionalised process that provides strategic guidance for coherent economic and social policies and priorities, that sets the main policy targets for the short and medium term, and that monitors implementation at the national level. The role could be filled by a ‘National Economic Council’, serving as an official policy coordination platform, along with other complementary reforms.

Social inclusivity

Revamping communications with different public spheres is key to promoting inclusiveness, transparency and policy predictability. This will require advancing public policy debates as well as developing communication strategies at all government levels. Effective communication improves the level of economic literacy and narrows the ‘credibility gap’, which in turn strengthens the credibility of economic policy.

Communication is also an important tool of accountability. As policy objectives and key performance indicators become better articulated, it allows the public to monitor and evaluate the government’s performance. Hence, designing and implementing a communication strategy is a necessary component of the process of economic policy formulation.

Complementarity

Although some programmes or policy measures may need longer to develop and materialise, due consideration should be given to phasing in these actions as elements of a larger compact on comprehensive reform.

Building an institutional process for economic policy management and coordination in MENA countries is essential to improve policy consistency and effectiveness.

Further reading

Al-Mashat, Rania (2017) World Economic Forum blog on globalisation, published during the annual conference in Davos.

Dimian, Hany, and Rania Al-Mashat (2015) ‘Helping Advance the Economic Policy Making and Management Process in Egypt: Initial Institutional Aspects for the Executive Branch’, Rockefeller Brothers and Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Gaspar, Vitor, Maurice Obstfeld and Ratna Sahay (2016) ‘Macroeconomic Management When Policy Space is Constrained: A Comprehensive, Consistent, and Coordinated Approach to Economic Policy’, IMF Staff Discussion Note No. 16/09.