In a nutshell

Unemployment has long been a defining characteristic of the Jordanian labour market, persisting even during periods of substantial economic growth; it was rising well before the emergence of Covid-19, and has remained consistently high since then.

Unemployment in Jordan (and across MENA) is widely believed to be a labour market insertion problem particularly affecting women, based on the high unemployment rates among youth and women; yet not only are most of the unemployed adults and men, but their shares of the total pool of unemployed have been growing over time.

To combat unemployment, policies should prioritise improving macroeconomic management, particularly addressing the budget deficit and public debt, while reversing the private sector trend towards low value-added, low-productivity activities; this does not eliminate the need to improve the labour outcomes for specific groups – in this case, unemployed youth and women.

Unemployment in Jordan has commonly been described as a youth and gender issue. The objective of this column is to assess the scale of the challenge in terms of total unemployment in the macroeconomy (the total ‘stock’ of unemployed Jordanians), which is not immediately obvious when examining the undeniably very high unemployment rates among young people and women. The statistical evidence in Jordan, in terms of age and gender composition of unemployment, is compared with data for other Arab states (excluding Jordan) and the rest of the world (excluding the Arab states).

In short, this column seeks to answer the question: ‘How much unemployment would remain in Jordan, if all unemployed youth and women were employed?’ The answer is: ‘A lot – in fact, most of it’.

Unemployment rates: highest among youth and women

As reported by Jordan’s Department of Statistics, the total unemployment rate was 21% in late 2024. Male unemployment was 19%, while the rate for women was notably higher at 31%. Youth aged 15-24 faced an average unemployment rate of 46%, with 40% for young men and 66% for young women. Among university-educated individuals, the unemployment rate was higher at 26%. The share of those out of work for more than one year (the long-term unemployed) in total unemployment was 48%.

These figures clearly indicate that reducing unemployment in Jordan is a challenging task.

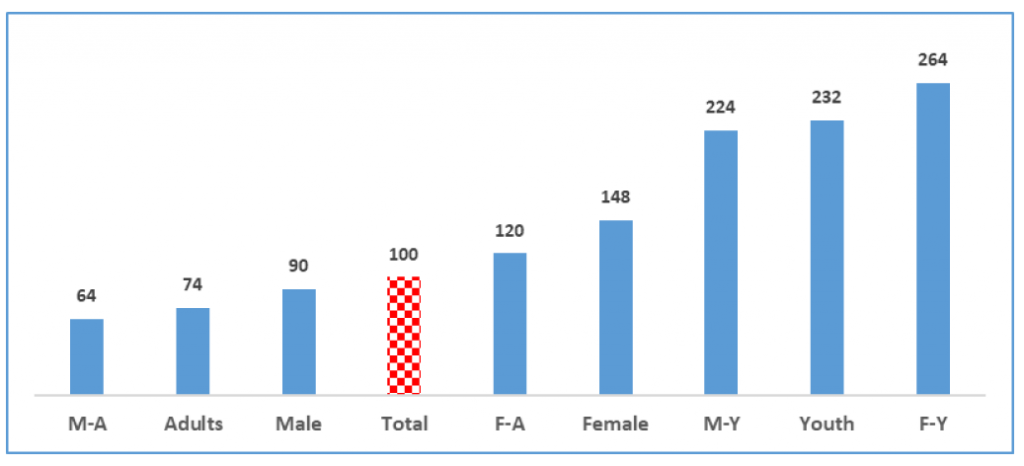

Using international statistics for reasons of comparability between Jordan and the Arab states and between Jordan and the rest of the world in the discussion that follows, Figure 1 shows the specific unemployment rates for youth and adult men and women relative to the total unemployment rate in the economy.

Compared with the total unemployment rate, the rate for adults was lower by nearly 25%. Among adults, the male rate was nearly 35% lower and the female rate 20% higher. Both male and female adults have lower rates than male and female young people whose rates exceed the total unemployment rate by more than 200%, as does the youth unemployment rate for both sexes. Averaging adults and young people, the male rate is 10% lower than the total unemployment rate, but the female rate is nearly 50% higher. These differences among the four subgroups are large.

Figure 1: Unemployment rates: highest for young people and women (unemployment rates indexed to total unemployment rate = 100)

Source: Extracted from ILOSTAT, January 2025.

Examining unemployment rates alone cannot answer the question, ‘How many unemployed Jordanians would remain, if policies eliminated unemployment among youth and women?’ This is because a high rate can correspond to a relatively small number of unemployed people.

In other words, it is a reduction in the number of unemployed individuals that affects the stock of unemployed and reduces the total unemployment rate. This may reduce the unemployment rates of subgroups differently, which can give rise to concerns. But both the arithmetic of unemployment and, more importantly, the causation of the argument are clear. This is examined below with reference to the shares of youth and women, as well as adults and men, within the pool of all unemployed.

Unemployment shares: largest among adults and men

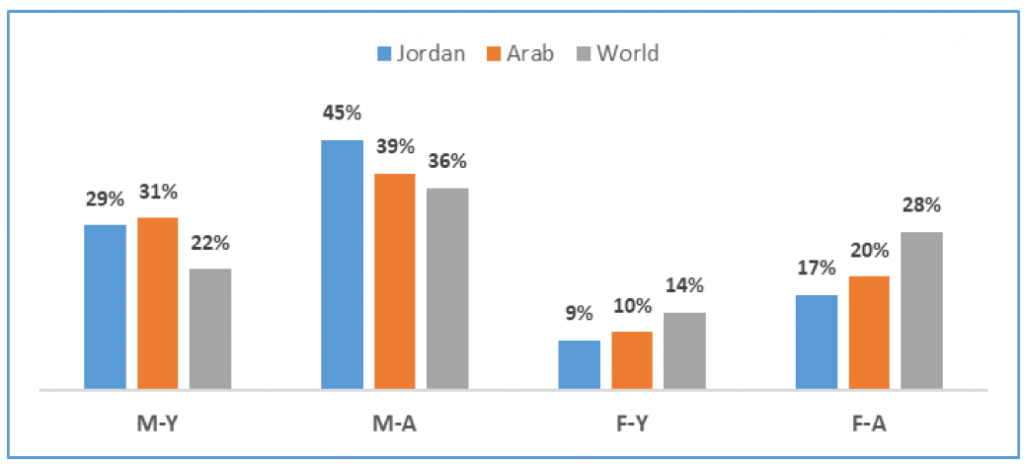

A different picture emerges when looking at unemployment shares of these four groups in total unemployment (Figure 2). Men in Jordan comprise almost half of the unemployed (45%) with male youth being the second largest group (29%). The unemployment share of Jordanian women is a distant third (17%). Although the unemployment rate of female youth is almost 50%, the highest rate of all groups, the share of female youth in total unemployment is less than 10% i.e. is the lowest among all groups.

Also noticeable is that the unemployment shares of both Jordanian women and female and male youth are lower even when compared with the average among Arab states. In this respect, Jordanian unemployment is rather exceptional even within the regional context. In other words, Jordan’s unemployment challenge mainly is an issue for the country’s men.

Figure 2: Three-quarters of all unemployed are men and two-thirds are adults (shares in total unemployment by age and sex, %)

Sources: Extracted from ILOSTAT, January 2025.

There are some differences when comparing the unemployment shares by age and sex in Jordan (and in the Arab states) to those in the rest of the world. While globally the unemployment share of men is largest (36%) followed by women (28%), in Jordan and the Arab states, the second largest group is male youth at around 30%. Also globally, the share of female youth is low, but it is lowest in Jordan and the Arab states. In other words, the size (not the rate) of female unemployment is more serious in the rest of the world than in the Arab states and especially in Jordan. Summarising, the unemployed population in Jordan today consists of nearly 75% men and 37% youth. Men make up the largest group among the unemployed, despite having the lowest unemployment rate. Young women, on the other hand, form the smallest group despite having the highest unemployment rate.

Trends in unemployment

The unemployment statistics presented above mask an underlying trend in Jordan, which aligns with sluggish economic growth, a shift towards lower value-added activities in the private sector, declining productivity and slow job creation, even during the economic boom of the 2000s.

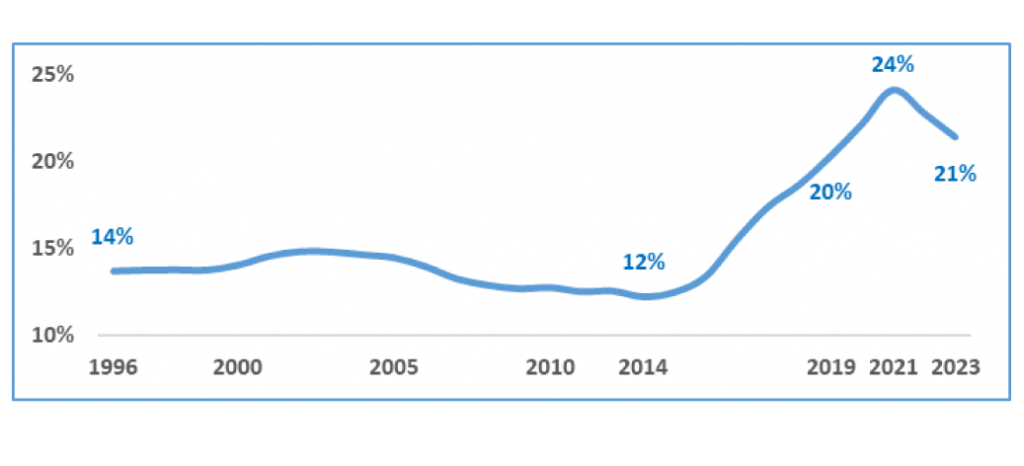

Looking at the last three decades, total unemployment oscillated between 12% and 14% until the mid-2010s. It then started rising fast and reached just under 20% before the pandemic. It peaked at 24% in 2021 before declining to 21% in 2023.

Figure 3: Unemployment: elevated during expansion and rising before the pandemic (total unemployment rate, %)

Sources: Department of Statistics.

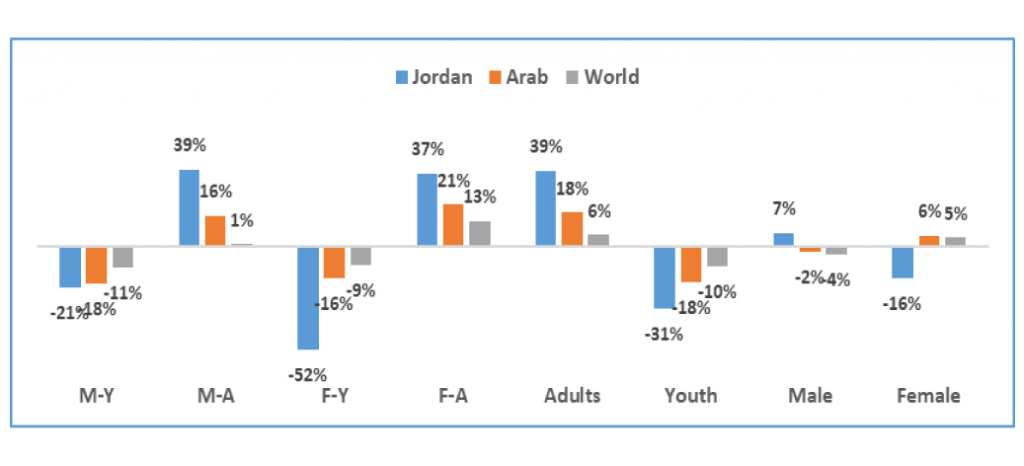

In terms of the composition of unemployment, the share of adults has increased globally since 2010. But the increase in Jordan has been double that of the Arab states (by nearly 40% compared with 18%) and more than six times higher than in the rest of the world (6%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The unemployment share of men and adults has increased, 2010-2023 (percentage change in unemployment shares, by age and sex)

Sources: Extracted from ILOSTAT, January 2025.

There are two notable trends in Jordan. The first is a 7% increase in the share of men, compared with decreases in the rest of the world, including the Arab states. The second is the share of women in Jordan decreased significantly by 16%, compared with increases in the other Arab states and the resdt of the world. While the shares of youth have declined globally, the decline in Jordan has been much steeper than in the Arab states and the rest of the world. Also compared with the rest of the world, in Jordan, the share of male youth declined twice as much, the share of all youth declined three times more, and the share of female youth declined five times more.

Policies

Addressing the challenge of reducing unemployment in Jordan requires acknowledging two facts. First, from an age perspective, adult unemployment has become a greater issue over time compared with youth unemployment.

Second, from a gender perspective, the share of unemployed women has been declining, while the share of unemployed men has been rising. In fact, since the end of the economic boom in 2009, the female unemployment rate increased by 27% (from 24.1% to 30.7%) and the male unemployment rate increased by 90% (from 10.3% to 19.6%). Similarly, female youth unemployment has been declining faster than male youth unemployment.

Combining youth and adults, the female share in employment has been increasing fast. According to the Department of Statistics, the female-to-male ratio of ‘net newly created jobs’ was 45% in 2023, compared with the ratio of female-to-male activity rate of 26% (the latter figure is nearly 50% larger than its value of under 18% in 2003).

The fact that the majority of the unemployed are adults and men suggests that unemployment is driven more by macroeconomic factors than by group-specific causes. Prominent among these factors are Jordan’s ‘twin deficits’ – that is, a fiscal deficit as public spending exceeds public revenues and has contributed to increasing public debt; and a current account deficit as imports exceed exports. The two deficits have choked off private sector development and its ability to create more jobs.

Jordan’s economy exhibits several commonly cited signs of ‘secular stagnation’. These include a combination of challenging characteristics such as:

- A relatively stable economy but insufficient aggregate demand and weaknesses in the private sector.

- Prolonged periods of low economic growth and low inflation.

- High unemployment.

- Declining population growth.

In addition, Jordan’s labour market is porous at both ends: skilled Jordanians are emigrating in large numbers, while low-wage non-Jordanians are increasingly hired as the economy shifts towards low-value, low-productivity activities. Overall, frictional, cyclical, seasonal, technological or voluntary factors can account for only a small part of unemployment.

Policies can support the specific groups they are designed to assist, such as youth and women. They have done so for decades, often with substantial support from international organisations. But they have not been able to decrease the bulk of unemployment that consists of adults and men and has been rising over time.

Addressing this challenge requires revitalising the economy, a key objective of the Economic Modernization Vision 2023-33, which calls for coordinated fiscal, monetary, structural and institutional policies.

In the meantime, if left unaddressed, youth and female unemployment can have profound economic and social consequences. The impact on young people can be substantial and linger throughout their lives. Gender inequality in the labour market not only affects women and their households, but also restricts the economy’s potential, creating an ‘output gap’ by underusing its human capital.

In conclusion, a deeper understanding of the nature and causes of unemployment in Jordan is needed. This calls for an analysis that extends beyond the scope of this column, the primary objective of which was to correct a misinterpretation of facts. Having done so, the key takeaway is that unemployment in Jordan is not confined to specific groups. It is a significant economic and social challenge that affects all Jordanians – youth and adults, women and men alike.

Further reading

Assaad, Ragui, and Colette Salemi (2018) ‘The Structure of Employment and Job Creation in Jordan: 2010-2016’, ERF Working Paper No. 1259.

Assaad, Ragui, and Caroline Krafft (2023) ‘Labour Market Dynamics and Youth Unemployment in the Middle East and North Africa: Evidence from Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia’, Labour 37(4).

European Investment Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and World Bank (2022) ‘Unlocking Sustainable Private Sector Growth in the Middle East and North Africa: Evidence from the Enterprise Surveys’.

European Training Foundation (2021) ‘Skills and Migration: Country Fiche Jordan’.

Gonzalez, Alvaro, and Hernan Winkler (2019) ‘Jordan Jobs Diagnostic’, Jobs Series No. 18, World Bank.

Government of Jordan (2023) ‘Economic Modernization Vision 2033’, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation.

Government of Jordan (2023) ‘Jordan Statistical Yearbook 2023’, Issue No. 74, Department of Statistics.

Kawar, Mary, Zina Nimeh and Tamara Kool (2022) ‘From Protection to Transformation: Understanding the Landscape of Formal Social Protection in Jordan’, ERF Working Paper No. 1590.

Razzaz, Susan (2017) ‘A Challenging Market Becomes More Challenging: Jordanian Workers, Migrant Workers and Refugees in the Jordanian Labour Market’, International Labour Organization.

Razzaz, Susan, and Farrukh Iqbal (2008) ‘Job Growth without Unemployment Reduction: The Experience of Jordan’, IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

Tzannatos, Zafiris (2021) ‘The Mismeasured, Misunderstood and Mistreated Arab Youth’, in Hassan Hakimian (ed.) Routledge Handbook on the Middle East Economy.

Tzannatos, Zafiris (2024) ‘Accelerating the Progress of Jordan towards the Sustainable Development Goals’, ERF Policy Research Report No. 55.

Tzannatos, Zafiris, and Ibrahim Saif (2023) ‘Assessing the Sustainability of Jordan’s Public Debt: The Importance of Reviving the Private Sector and Improving Social Outcomes’, ERF Working Paper No. 1649.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.