In a nutshell

Egypt has liberalised its external trade: this has led to an increase in both exports and imports, but trade structure has not changed significantly over time; exports remain highly concentrated in traditional products.

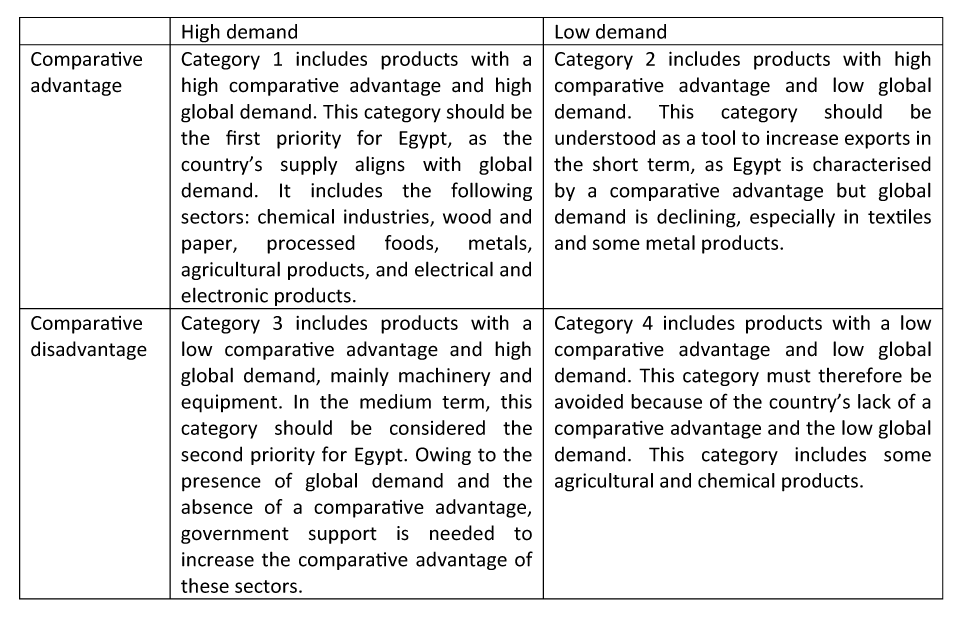

This first priority for Egyptian exports should be where the country’s comparative advantage aligns with high global demand; that includes the following sectors: chemical industries, wood and paper, processed foods, metals, agricultural products, and electrical and electronic products.

At the institutional level, Egypt’s government needs to expand the country’s trade agreements to address issues that will improve their effectiveness in terms of sustainable development.

Over several decades, Egypt has liberalised its external trade. This has led to an increase in both exports and imports, but their structure has not changed significantly over time. This can be attributed to several reasons:

- First, the investment climate does not draw in investors, and there is no clear national vision for an effective industrial policy.

- Second, traditional products with little value added dominate exports, and these products rely heavily on imported raw materials. The same holds for foreign direct investment (FDI), which is concentrated in the oil industry and has not succeeded in creating global value chains or jobs.

- Third, the negligible rise in exports results from the fact that the majority of trade agreements that Egypt has signed are shallow. Research on trade typically distinguishes between shallow and deep agreements, with the former being agreements that are limited to tariff removal and the latter going beyond that to include non-tariff measures, services and other non-trade provisions.

- Fourth, non-tariff measures still impede both imports and exports.

In terms of structure, Egypt’s merchandise exports are less diversified than those of Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia. For example, fuel still represents 25% of total merchandise exports even thought it has declined over time (from 33% in the early 2000s). At the same time, while Egypt’s manufactured exports are lower than those all comparator economies and lower-middle-income countries (46.5%), its food exports are relatively high (28%).

In addition, manufactured exports are relatively traditional mainly concentrated in processed food, chemicals and textiles. In fact, the share of medium and high exports confirms this. Both are much lower than other diversified economies of the MENA region.

This analysis points out that Egypt has failed to upgrade the structure of its exports. Three main reasons can explain this:

- First, the lack of efficient institutions (especially a discouraging investment climate and a lack of competition policy) that are essential for complex products help to explain these developments.

- Second, despite the abundance of blue-collar workers that are required for most industries in Egypt, they remain unskilled. This is why more investments in technical and vocational education to help such workers acquire the needed skills should be a top priority.

- Finally, specialisation in capital-intensive sectors helps to explain why exports have not upgraded and failed to generate many jobs.

Implications for policy

To unleash the export potential of Egypt, it is important to develop a forward-looking strategy that considers both supply and demand factors. While the supply-related factors take account of the country’s competitiveness, demand-related factors should consider the global demand. Products can therefore be divided into four groups.

A new export strategy for Egypt should also be inclusive and supportive of sustainable development to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Potential reforms include the following:

- First, for SDG9 on industry and innovation, it is crucial to attract and channel more FDI into the manufacturing sector in general and priority sectors in particular, to develop global value chains and create more jobs. This will require a mainstreaming of industrial policy within trade policy. In other words, more coordination is needed between industrial priorities and trade policy developments.

- Second, for SDG8 on decent employment, the government should encourage domestic investment and channel FDI into the manufacturing sector to increase exports. A freer environment is associated with less informality, which will help to achieve this objective.

- Third, for SDG5 on gender equality and SDG10 on reduced inequalities, it is important to remove service restrictions and non-tariff measures that negatively affect wages in order to make trade freer. This will lead to increased competition and higher demand for more productive workers, thus increasing wages and reducing inequalities.

- Finally, at the institutional level, the government needs to expand the country’s trade agreements to address issues that will improve their effectiveness in terms of sustainable development.

Further reading

Aboushady, Nora, and Zaki, C. (2021) ‘Trade and SDGs in the MENA Region: Towards a More Inclusive Trade Policy’, ERF Policy Brief No. 56.

Fiorini, Matteo, and Bernard Hoekman (2018) ‘Services trade policy and sustainable development’, World Development 112: 1-12.

Xu, Zhenci, Yingjie Li, Sophia Chau, Thomas Dietz, Canbing Li, Luwen Wan, Jindong Zhang, Liwei Zhang, Yunkai Li, Min Gon Chung and Jianguo Liu (2020) ‘Impacts of international trade on global sustainable development’ , Nature Sustainability 3(11): 964-71.

Zaki, Chahir (2022) ‘Trade as an engine for sustainable development and growth’, in Financing Sustainable Development in Egypt Report edited by Mahmoud Mohieldin, League of Arab States.

Zaki, Chahir (2024) ‘Accelerating the progress of Egypt towards the Sustainable Development Goals’, ERF and Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development, forthcoming.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.