In a nutshell

The overall trends in women’s empowerment in decision-making in Arab households between 2016 and 2022 are encouraging across Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine and Tunisia.

Lebanon has consistently led the way, showing the highest levels of empowerment; at the same time, Algeria and Egypt continue to face significant challenges, with consistently low levels of empowerment and little improvement in their relative rankings.

While progress has been notable, it is far from complete; policy-makers should focus on accelerating the positive trends by addressing the underlying social and economic factors that sustain gender inequalities in household decision-making.

Freedom is a critical dimension of wellbeing. Yet as previously argued in a column here (Makdissi, 2024a), it remains underrepresented in most multidimensional assessments of welfare, inequality and poverty.

Women’s empowerment within households offers a clear intersection between freedom and wellbeing, particularly through the lens of Sen’s capability approach (Sen, 1999). In this framework, empowerment translates into increased freedom for women, which means increased capabilities, that is, an expansion of the set of available functionings. This column explores the evolution of women’s empowerment within Arab households between 2016 and 2022.

As a proxy measure of women’s empowerment within the household, we use data from the Arab Barometer, specifically an ordinal variable that captures the degree of agreement with the statement A man should have final say in all decisions concerning the family. The distribution of this variable within a society serves as a key indicator of the social norms that affect gendered power dynamics in household decision-making.

A decline in agreement with this statement suggests progress in the distribution of decision-making power within households. Since this question was first asked in Wave IV of the Arab Barometer, we use data from Wave IV (2016) and Wave VII (2021-22), the last wave available of the Arab Barometer. For simplicity, we refer to estimates from Wave VII as 2022 estimates.

According to Roche (2022), since this question was first introduced in the Arab Barometer in 2016, the proportion of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing with it has steadily decreased. This decline reflects a broader shift toward granting women more autonomy in household decisions, contributing to their overall empowerment and aligning with the expansion of freedoms emphasised in Sen’s capability approach.

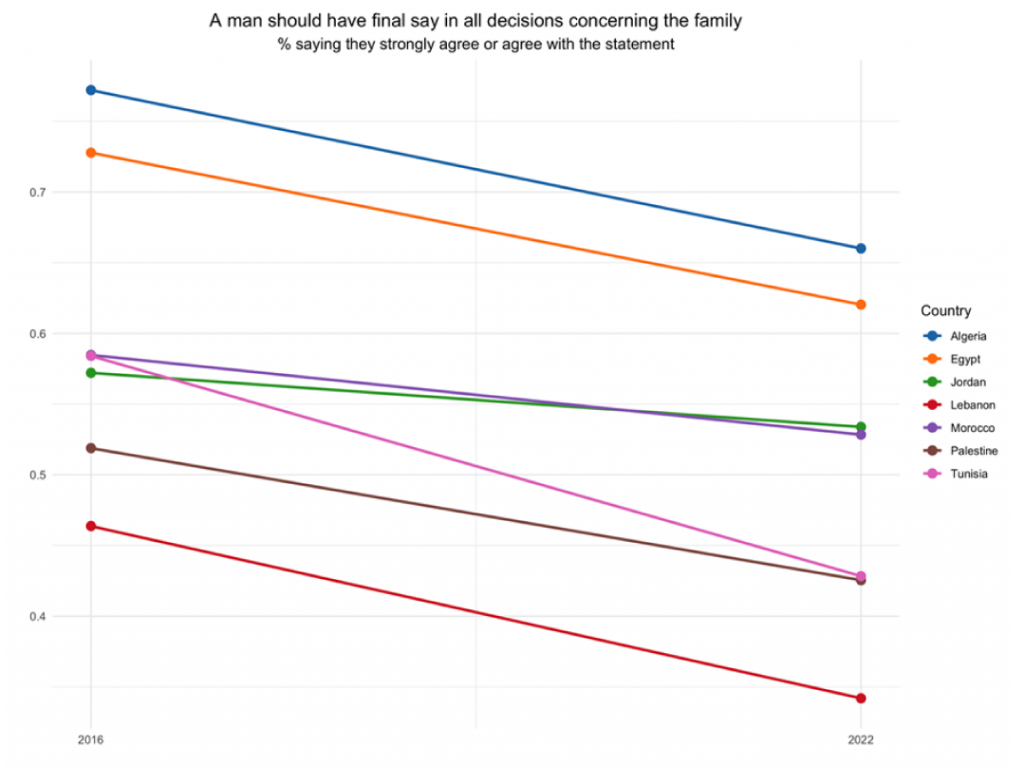

Figure 1 represents the proportion of the population agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement A man should have final say in all decisions concerning the family in the seven countries for which this question was asked in 2016 and 2022: Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine and Tunisia.

Figure 1: Share of people agreeing that men should have the final say in family decisions

In 2016, except for Lebanon, more than 50% of the population of each country agreed or strongly agreed with the statement. Between 2016 and 2022, the proportion of the population agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement decreased in all seven countries. In 2022, there are now three countries (Lebanon, Palestine and Tunisia) where less than 50% of the population agree or strongly agree with the statement.

Analysing survey data

In previous columns here, on freedom (Makdissi, 2024a) and trust (Makdissi, 2024b), I highlight the limitations of splitting in two the sample based on a threshold category of an ordinal variable, as it often overlooks valuable information. The same challenge applies to the variable that we use as a proxy for women’s empowerment within the household, which captures the degree of agreement with the statement A man should have final say in all decisions concerning the family.

This variable has four categories: Strongly agree, Agree, Disagree and Strongly disagree. We assume that empowerment increases as we move from the first (Strongly agree) to the last (Strongly disagree) category.

One could think that using summary statistics, such as the mean, could exploit the richness of the information. But as I discussed in the previous columns, using a summary statistic like the mean for an ordinal variable can lead to results that are not robust to changes in the numerical scale applied to the variable.

This issue is linked to the fact that only the ranks are meaningful for ordinal data. The intensity of the distance between categories is not. That is why any increasing numerical scale applied to an ordinal variable conveys the same information about ranks but does not carry any valid information about the magnitude of differences between categories.

In this context, Allison and Foster (2004) provide a valuable framework for analysing ordinal variables. They demonstrate that if the cumulative distribution of this ordinal variable for population A first-order dominates the cumulative distribution for population B, then the mean of the ordinal variable for population A will be higher than for population B, regardless of the numerical scale applied.

As explained in my previous columns, the first-order dominance for an ordinal variable can be visualised using pie charts. Applying this approach to our empowerment variable, the cumulative distribution of women empowerment for population A first-order dominates the cumulative distribution for population B if:

- The pie chart segment representing the Strongly agree category is smaller in population A’s pie chart.

- When combining the Strongly agree and Agree segments, this combined segment should still be smaller in population A’s pie chart.

- Adding the Disagree segment to the previous categories, the combined segment should still be smaller in population A’s pie chart.

Distributions of empowerment across seven Arab countries

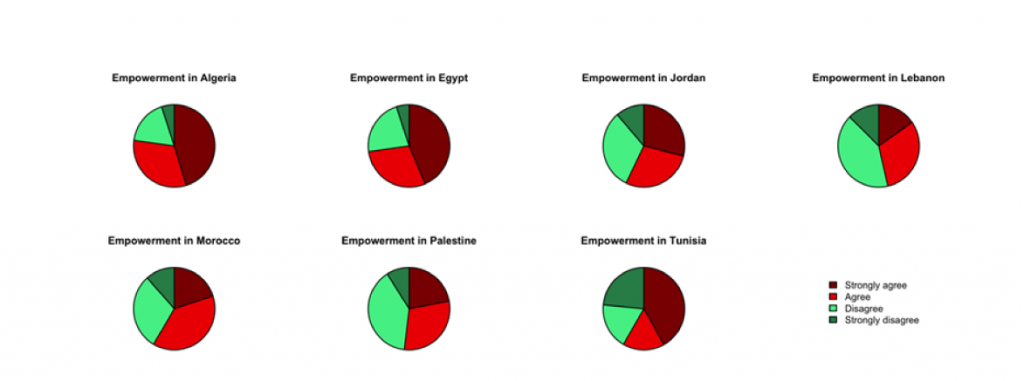

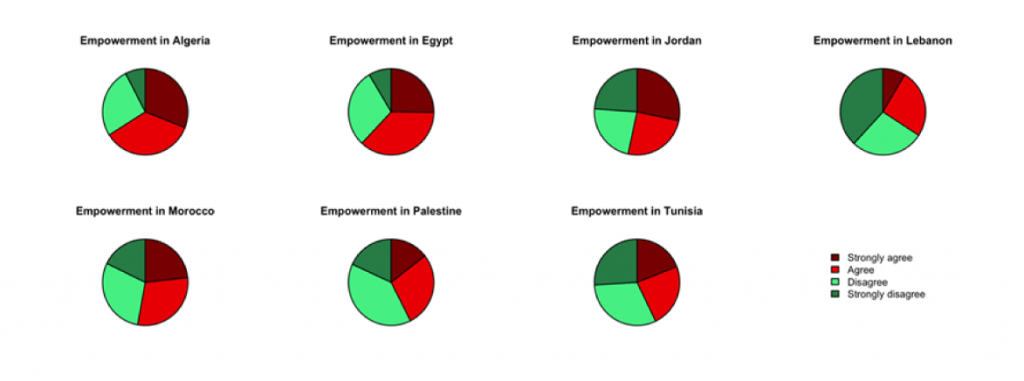

Figures 2 and 3 show the distributions of empowerment across seven Arab countries in 2016 and 2022. By comparing the pie charts and applying the concept of first-order dominance, we analyse how average empowerment has shifted over time and assess the rankings of these countries. Across the seven Arab countries, average empowerment generally increased between 2016 and 2022, except in Morocco, where the change is not robust. Average empowerment increased or decreased in Morocco depending on the numerical scale used.

Figure 2: Women’s empowerment in the Arab world, 2016

Figure 3: Women’s empowerment in the Arab world, 2022

In 2016, Lebanon showed higher average empowerment than all countries except Tunisia, where the ranking was not robust to changes in the numerical scale. At the lower end of the spectrum, Algeria and Egypt exhibited lower average empowerment than all other countries, although the ranking between these two was not robust. Palestine showed higher average empowerment than Jordan, while all other rankings were not robust to changes in the scale used.

By 2022, Lebanon further solidified its position with the highest average empowerment, surpassing all other countries. In contrast, Algeria had the lowest average empowerment, being outperformed by every other country. Egypt, just above Algeria, had lower average empowerment than all other countries, except for Jordan, where the ranking remained non-robust. Morocco showed lower average empowerment than Palestine and Tunisia, while Jordan lagged Tunisia. The other rankings were not robust to numerical scale changes.

In summary, the trends indicate a general increase in average empowerment between 2016 and 2022. Lebanon maintained and even strengthened its position as the country with the highest average empowerment. Morocco experienced more complex dynamics, with no definitive trend emerging, while Algeria consistently exhibited the lowest average empowerment across both years, being outperformed by most other countries.

Socio-economic inequalities in women’s empowerment

Looking solely at average empowerment levels does not sufficiently capture the complexity of women’s empowerment in a country. To complete the picture, we need an analysis that considers socio-economic inequalities in women’s empowerment.

I use Wagstaff’s (2002) achievement index to provide a more nuanced analysis. The class of achievement indices used in that study includes a parameter of aversion to socio-economic inequalities. I use a value of 2 for this parameter as it is linked with the social preferences underlying the canonical Gini and concentration indices. The achievement index increases with a rise in the average level of empowerment (as measured by disagreement with male-dominant decision-making). It also rises with a decrease in socio-economic inequality in its distribution, as measured by the canonical concentration index.

This approach makes it possible to capture both average empowerment and the extent to which empowerment is equitably distributed across socio-economic ranks. To impute socio-economic ranks, I use the education variable available in the Arab Barometer since the income question is not the same in 2016 and 2022, and it has too many missing values (Makdissi et al, 2024).

Unfortunately, in the presence of an ordinal variable, summary statistics such as concentration or achievement indices suffer from the same issue as the average: the ranking may be dependent on the choice of a specific numerical scale (Zheng, 2008; Makdissi and Yazbeck, 2014 and 2017).

Building on the insight from Allison and Foster (2004), Makdissi and Yazbeck (2017) show that if each observation is weighted by its associated value from the social weight function underlying the achievement index, one can apply the first-order dominance condition described above on the reweighted distribution to produce robust ordering in terms of the achievement index.

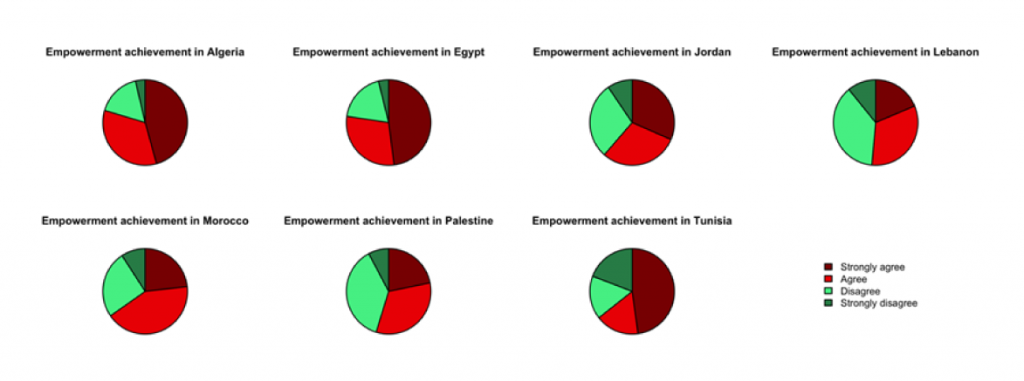

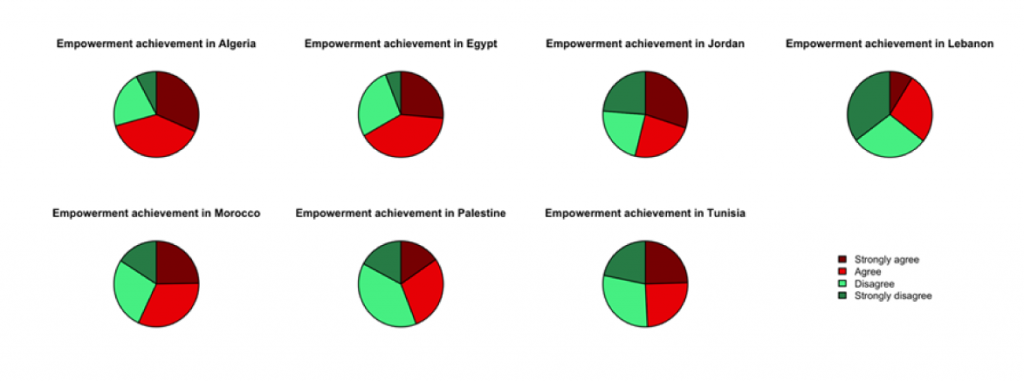

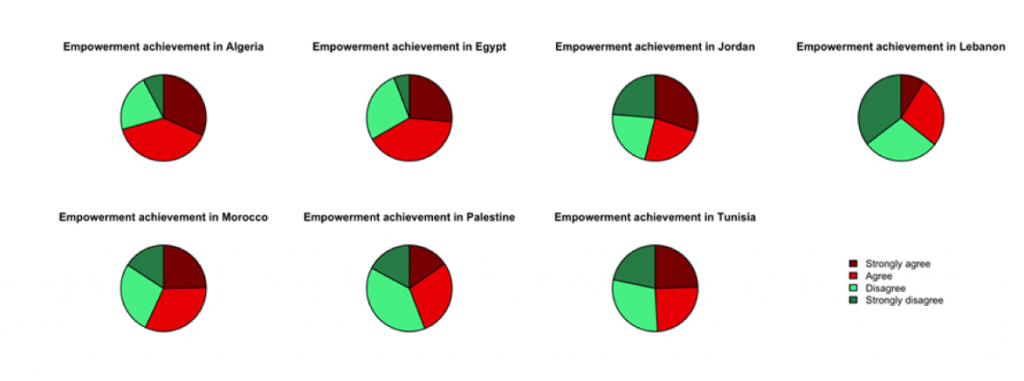

Figures 4 and 5 show these reweighted distributions of empowerment across seven Arab countries in 2016 and 2022. By comparing the pie charts and applying the concept of first-order dominance, we analyse how empowerment achievement has shifted over time and assess these countries’ rankings.

Figure 4: Women’s empowerment achievement in the Arab world, 2016

Figure 5: Women’s empowerment achievement in the Arab world, 2022

The dynamics of empowerment achievement between 2016 and 2022 largely follow the same pattern as average empowerment, with increases in most countries. But in Morocco, the change in empowerment achievement is still not robust. It depends on the numerical scale used, and empowerment can either increase or decrease.

In 2016, Lebanon showed higher empowerment achievement than all other countries except Tunisia, where the ranking was not robust to changes in the numerical scale. At the lower end of the spectrum, Algeria and Egypt exhibited lower empowerment achievement than the other countries, although the ranking between these two was not robust. Palestine showed higher empowerment achievement than Jordan, while all other rankings were not robust to scale changes. These patterns are similar to the average empowerment rankings, indicating that both measures consistently reflect the relative positions of the countries in 2016.

In 2022, the rankings for empowerment achievement show some differences compared with average empowerment. Egypt and Algeria maintained their position at the bottom of the rankings, similar to 2016. Palestine is ahead of Morocco in empowerment achievement, which marks a change from the average empowerment rankings. Most of the other rankings in 2022 were not robust to changes in the numerical scale.

The trends in empowerment achievement between 2016 and 2022 reflect an overall increase in empowerment, similar to average empowerment. Lebanon continues to lead, with the highest empowerment achievement, while Algeria and Egypt consistently show the lowest levels of empowerment achievement.

Conclusions

The overall trends in women’s empowerment across the seven Arab countries between 2016 and 2022 are encouraging. In nearly all countries, there has been a notable increase in both average empowerment and empowerment achievement, indicating progress toward more equitable household decision-making dynamics.

Lebanon has consistently led the way, showing the highest levels of empowerment. At the same time, Algeria and Egypt continue to face significant challenges, with consistently low levels of empowerment and little improvement in their relative rankings.

But while the progress over this period is notable, it is far from complete. Even with these positive trends, the proportion of the population agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement that A man should have final say in all decisions concerning the family remains above 40% in most countries as of 2022. This suggests that traditional gendered power dynamics are still profoundly entrenched while social norms slowly shift.

Policy-makers should focus on accelerating these positive trends by addressing the underlying social and economic factors that sustain gender inequalities in household decision-making. Further efforts are needed to promote gender equality.

Further reading

Allison, RA, and JE Foster (2004) ‘Measuring health inequality using qualitative data’, Journal of Health Economics 23: 505-24.

Makdissi, P (2024a) ‘Freedom: the missing piece in analysis of multidimensional wellbeing’, The Forum: ERF Policy Portal.

Makdissi, P (2024b) ‘Shifting public trust in governments across the Arab world’, The Forum: ERF Policy Portal.

Makdissi, P, W Marrouch and M Yazbeck (2024) ‘Monitoring poverty in a data-deprived environment: The case of Lebanon’, forthcoming in Review of Income and Wealth.

Makdissi, P, and M Yazbeck (2014) ‘Measuring socioeconomic health inequalities in presence of multiple categorical information’, Journal of Health Economics 34: 84-95.

Makdissi, P, and M Yazbeck (2017) ‘Robust rankings of socioeconomic health inequality using a categorical variable’, Health Economics 26: 1132-45.

Roche, MC (2022) ‘Gender attitudes and trends in MENA’, Arab Barometer Gender Report.

Sen, AK (1999) Development as Freedom, Alfred A Knopf.

Wagstaff, A (2002) ‘Inequality aversion, health inequalities and health achievement’, Journal of Health Economics 21: 627-41.

Zheng, B (2008) ‘Measuring inequality with ordinal data’, Research on Economic Inequality 16: 177-88.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.