In a nutshell

Arab countries’ participation in global value chains has been modest to date; they are more engaged with forward GVCs since their involvement is still concentrated in being providers of raw materials as inputs for the production processes of other countries.

There are big variations among Arab countries in the factors that determine engagement in GVCs; in general, they are in relatively modest position compared with the rest of the world in terms of infrastructure, trade facilitation and the quality of institutions.

Being better engaged in GVCs should not be seen as a goal in itself, but rather as a tool to help Arab countries address some of their deep structural problems, including a lack of export diversification, low productivity, skills shortages and financial constraints.

Global value chains (GVCs) have become an important driver of growth and development for many countries, both developed and developing. Indeed, GVCs now account for 70% of global trade and they are a dominant feature of the world economy (Strategy and PWC Network, 2023).

Their growing importance in shaping the trade and geographical location of many industries has altered traditional thinking about international trade, and it has led many countries to compete to be part of them. At the same time, recent shocks to the world economy, including the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have led to a changing landscape for GVCs. National security considerations as well as economic ones are now shaping GVCs. A number of Arab countries stand to gain from this reshaping of the world map of GVCs, if appropriate policies are adopted. This column aims to answer a number of relevant questions: where do Arab countries stand now with GVCs? What are the main determinants of engagement in GVCs? And what are the expected benefits for Arab countries from joining GVCs?

Where do Arab countries stand with GVCs?

The engagement of Arab countries in GVCs has been modest to date. The region is among those least engaged in GVCs, whether backward participation (which is associated with firms importing inputs to be used in the production of exports) or forward participation (when firms export domestic inputs for use in the exports of other countries.)

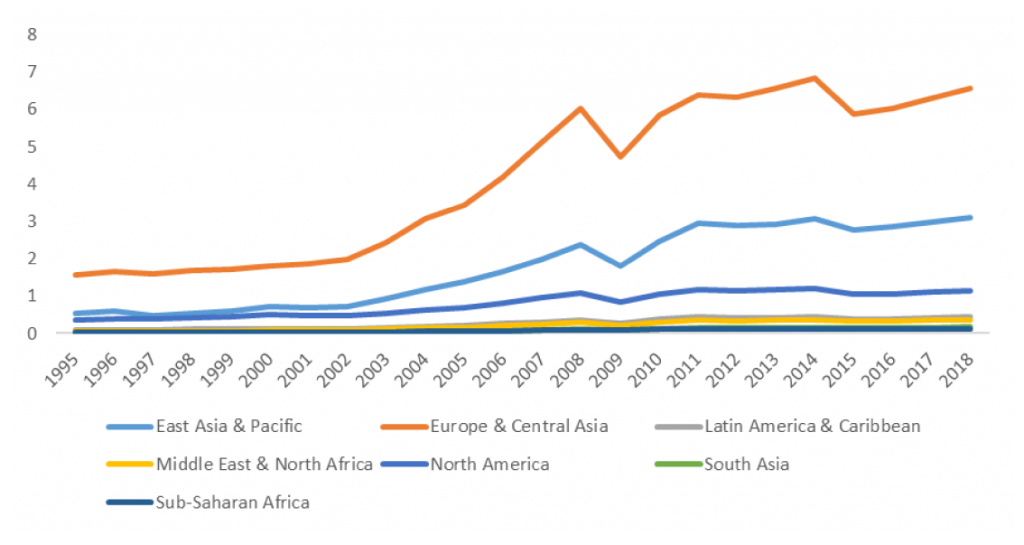

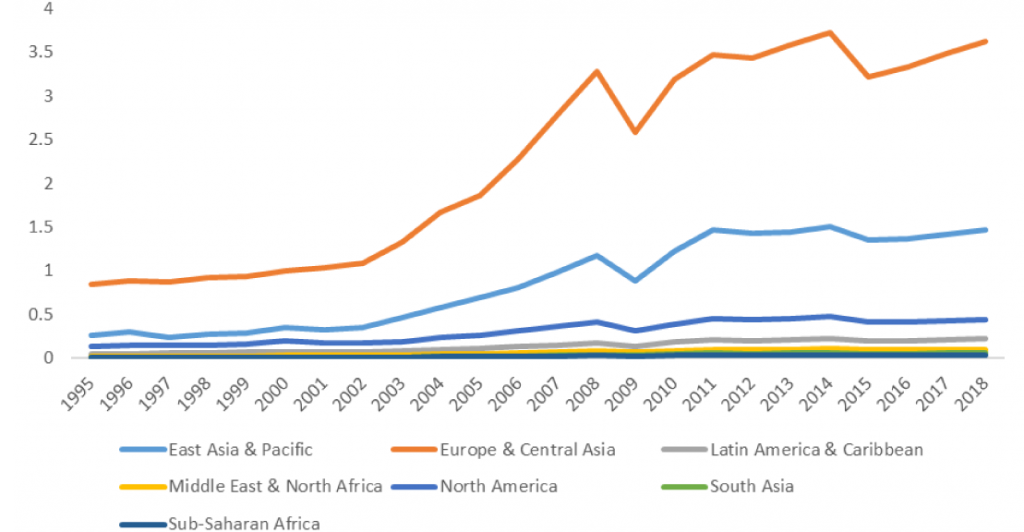

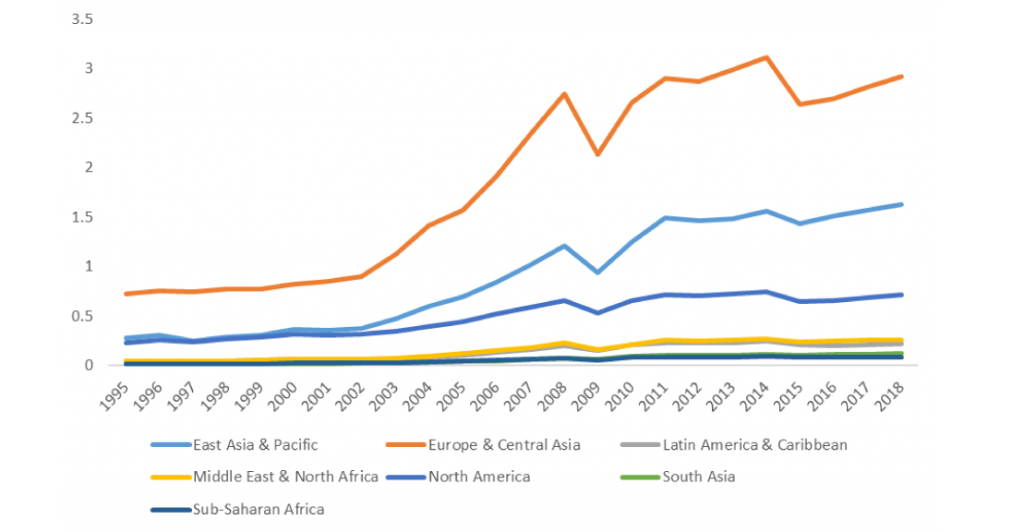

Figures 1, 2 and 3 reveal that Arab countries (part of Middle East & North Africa, but with the addition of Iran, Israel and Malta, following the World Bank definition) together with Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America & Caribbean are the world’s least integrated in terms of GVCs.

Arab countries are in a relatively better position with forward GVCs than backward GVCs. The reason is that their participation is still concentrated in being providers of raw materials as inputs for the production processes of other countries.

Figure 1: GVC participation – by region (billion US dollars)

Figure 2: Backward GVC participation – by region (billion USD)

Figure 3: Forward GVC participation – by region (USD)

What are the determinants of engagement in GVCs?

Following Ezzat and Zaki (2023) and Kowalski et al (2015), there are several factors that determine engagement in GVCs, including domestic market size, the level of development, industrial structure, geographical location, openness to trade and foreign direct investment (FDI), logistics and trade facilitation, the quality of infrastructure and the quality of institutions.

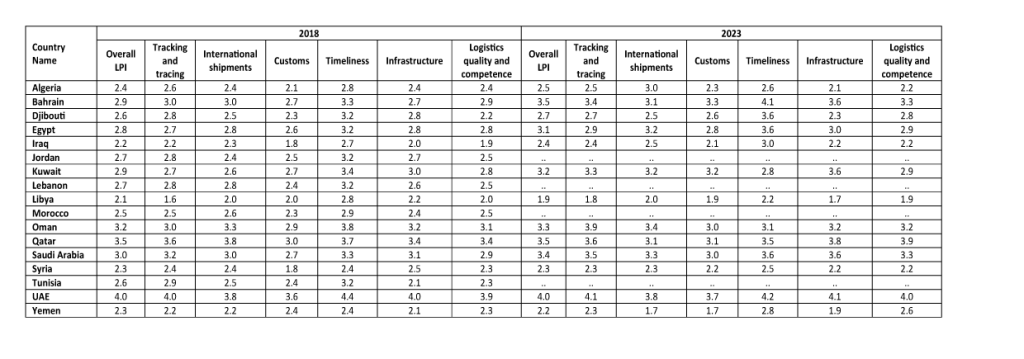

For sure, Arab countries differ significantly among each other in such determinants, and hence it is not expected that all of them are potential candidates for being more engaged in global GVCs. In general and as identified by ESCWA (2017), Arab countries are in a relatively modest position compared with the rest of the world in terms of infrastructure and the quality of institutions.

Arab countries that have a potential to be candidates based on a number of such determinants include Egypt, Morocco and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – see Table 1. Yet even these countries differ significantly among themselves, and although they might be scoring well on some of the determinants, they perform modestly in others. But each of them can build on the comparative advantage that they enjoy.

For example, Egypt has a large domestic market, a unique geographical location and an acceptable industrial infrastructure, whereas the UAE enjoys a significant logistical and trade facilitation position, as well as sound institutional infrastructure. Morocco benefits from a relatively well-developed industrial infrastructure and an advantageous geographical location. What the three countries have in common is that they are more involved in forward linkages rather than backward linkages, acting as suppliers of raw materials and inputs for the rest of the value chain, rather than using the inputs of the value chain and providing domestic value added on the intermediate and final levels.

Table 1: Logistics Performance Index for Arab countries (2018 and 2023)

What are the expected benefits from joining GVCs?

Being better engaged in GVCs should not be seen as a goal in itself, but rather as a tool to help Arab countries address some of their deep structural problems. For example, most of them suffer from a lack of diversification of their exports as well as a relatively low share of non-oil exports to their GDP. Being engaged in GVCs can help Arab countries to overcome such problems.

Moreover, empirical evidence indicates that GVCs help in enhancing the productivity of firms, upgrading labour skills in Arab countries, increasing income per capita and, in some cases, overcoming financial constraints (Ayadi et al, 2020; Gnatenko et al, 2018).

Yet such benefits of GVCs cannot be considered windfall gains and, in many cases, they are concentrated in upper-middle- and high-income countries (Gnatenko et al, 2018). They can only be achieved if the aforementioned determinants, especially those associated with infrastructure and trade facilitation, are present.

The way forward

To reap the benefits of being engaged in GVCs, Arab countries need to focus on the products where they enjoy a natural comparative advantage, regardless of whether they are associated with forward or backward linkages. Yet they need to focus on changing the comparative advantage into a competitive one by enhancing the associated services provided at the borders, increasing the extent of domestic value added (whether by manufacturing and/or including services), improving logistics and trade facilitation aspects.

Moreover, and as identified by Ezzat and Zaki (2023) and Bousnina and Gabsi (2022), improving the quality of institutions (for example, competition law) will help to enhance engagement with GVCs, as it plays a role in reducing transaction costs.

On another front, engagement in GVCs is no longer a pure economic decision, but rather dependent on political economy factors, with national security playing an increasing role (Zahoor et al, 2023). This implies that political and diplomatic ties are increasingly playing a role that cannot be neglected, especially when ‘nearshoring’ is playing a greater role than more conventional offshoring activities.

The concentration of Arab countries in the forward linkages segment of GVCs implies the need to get more engaged in the backward linkages segment. This is associated with climbing the ladder of manufacturing and technology, and intensifying the ‘servicification’ process domestically.

In other words, increasing domestic value added should be thought of not through the entire production process, but rather in the intermediate and final parts of the production process, as well as by improving and increasing the role of services in the production process.

Further reading

Ayadi, Rim, Giorgia Giovannetti, Enrico Marvasi and Chahir Zaki (2020) ‘Global Value Chains and the Productivity of Firms in MENA countries: Does Connectivity Matter?’, Working Paper No. 03/2020, DISEI, Universita degli Studi di Firenze.

Bousnina, Rihab, and Foued Badr Gabsi (2022) ‘Global Value Chain Participation, Institutional Quality and Current Account Imbalances in the MENA Region’, ERF Working Paper No. 1556.

ESCWA, Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (2017) ‘Transport and Connectivity to Global Value Chains: Illustrations from the Arab Region’, E/ESCWA/EDID/2017/3.

Ezzat, Asmaa, and Chahir Zaki (2024) ‘On Competition Policy and Global Value Chains: A de jure and de facto Analysis’, paper presented at the African Growth Dynamics Conference, OFCE, Paris, September (unpublished).

Gnatenko, Anna, Faezeh Raei and Borislava Mircheva (2018) ‘Global Value Chains: What are the Benefits and Why Do Countries Participate?’, IMF Working Paper No. WP/19/18.

Kowalski, Przemyslaw, Javier Lopez Gonzalez, Alexandros Ragoussis, Cristian Ugarte et al (2015) ‘Participation of Developing Countries in Global Value Chains: Implications for Trade and Trade-Related Policies’, OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 179.

Strategy and PWC Network (2023) ‘Reconfiguring Global Value Chains: Green Advantage Middle East’. Zahoor, Nadia, Jie Wu, Huda Khan and Zaheer Khan (2023) ‘De‑globalization, International Trade Protectionism, and the Reconfigurations of Global Value Chains’, Management International Review 63: 823-59.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.