In a nutshell

The transition to renewable energy promises to ensure energy security as well as social objectives of inclusiveness and equity; more importantly, it promises to create substantial net jobs and better paying jobs in manufacturing, engineering, construction and R&D.

The adoption of green energy technologies – such as solar power, wind energy, biomass, green hydrogen and hydropower – makes necessary the establishment of new supporting and downstream industries, leading to job creation across various sectors.

The MENA region is at the cusp of a potential new era of employment generation – but achieving it will take commitment, political will, adequate infrastructure, financial resources, skills development, and regional and international cooperation.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region faces many economic and environmental challenges: limiting emissions at home and abroad; managing its energy use efficiently; creating sufficient jobs for its growing population; dealing with its historically high unemployment rates of youth and women; improving its resiliency in dealing with natural disasters and the expected high economic costs of climate change; and weaning itself off heavy dependence on non-renewable energy and income sources.

Together, these challenges leave MENA with no option but to expedite its transition to renewable energy. Factoring in the increased likelihood of fossil fuels becoming stranded assets as countries and industries abandon fossil fuels, the region could be at the threshold of a major economic crisis if it delays its transition away from its heavy dependence on fossil fuels.

The region remains home to the highest levels of unemployment and particularly youth unemployment in the world. It is also a region where low participation rates of women in the labour force and their under-representation in leadership and high-paying positions are defining characteristics.

The transition to renewable energy has been conceived, right from the outset, as a social project to be undertaken by the region to capitalise on the net socio-economic and environmental benefits of a speedy, yet careful and ‘just’ transition plan to renewable energy. This is increasingly becoming possible with new international and regional funding opportunities for more environmentally friendly development that is capable of sustaining credible alternative income dividend streams, new exports, more productive and diversified economies, and sufficient jobs for the growing populations and the expanding labour supply.

The transition to renewable energy is also promising to ensure energy sufficiency and security, as well as potentially meeting social objectives of inclusiveness and equity. But more importantly, it promises to create substantial net jobs and better paying jobs in manufacturing, engineering, construction, and research and development (R&D).

Job creation in the renewable energy sector

The adoption of renewable energy technologies – such as solar power, wind energy, biomass, green hydrogen and hydropower – makes necessary the establishment of new supporting and downstream industries, leading to job creation across various sectors (see Tables 1 and 2).

The region, with its abundant solar irradiation and wind resources, has immense potential for renewable energy projects. As a result, the construction, installation and maintenance of renewable energy infrastructure will require a skilled workforce, contributing to several direct job opportunities in engineering, manufacturing, construction, business and project management.

Research, development and innovation

Investments in renewable energy initiatives in several developed and developing countries have stimulated R&D activities, fostering innovation and technological advancements. Their experience suggests that this could be expected in MENA. Governments and private entities in the region are increasingly investing in clean energy R&D, aiming to develop efficient and cost-effective renewable energy systems.

This will create employment opportunities for scientists, engineers, technicians, and blue- and white-collar labour specialising in renewable energy R&D. The growth of R&D centres and innovation hubs promotes knowledge transfer and will enhance the region’s technical expertise.

Supply chain and manufacturing

It is to be expected that green energy projects would entail the production and installation of renewable energy equipment, such as solar panels, wind turbines and energy storage systems. Establishing a robust local supply chain and manufacturing capabilities can significantly contribute to job creation. By supporting the production of renewable energy components within the region, a few examples are already being established. MENA countries can reduce their dependence on imports and develop a competitive advantage in the global green energy market.

This will lead to employment opportunities in manufacturing, assembly, logistics and related support services. In addition, there is the expanding potential of moving downstream and off-stream to the manufacture of electric vehicles (EVs), a prospect that is already being rooted in several countries in the region including Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and a host of ancillary activities such as charging stations and batteries.

Energy efficiency and retrofitting

Promoting energy efficiency measures and retrofitting existing infrastructure for improved energy performance can also generate employment opportunities. As the countries of the region seek to optimise energy consumption and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, there will be a demand for professionals specialising in energy audits, building retrofits and energy management.

Industries involved in the production and installation of energy-efficient equipment, such as lighting systems and HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) solutions, will also witness growth and create additional jobs.

Skills development and training

The transition to green energy makes necessary the development of a skilled workforce capable of meeting the demands of the evolving energy landscape. Governments and educational institutions in the region can play a vital role by providing training programmes and vocational courses focused on renewable energy technologies, energy efficient systems and products.

By equipping individuals with the necessary skills, the region can enhance its human capital, fostering employment opportunities and sustainable development in the green and renewable energy sector.

The agglomeration potential of energy-intensive industries

Unlike fossil fuels, most green energy is not easily transportable. Energy-intensive industries can no longer be separated easily and cheaply from the sources of energy.

This could give the region a comparative cost advantage to attract energy-intensive industries in heavy metals, chemicals and energy to locate in the region, thereby creating manufacturing hubs that generate substantial jobs for all types of skills and occupations. The availability of huge deserts and underused spaces in the region could be an attractive factor for locating manufacturing facilities away from population centres.

In contrast, green hydrogen is not only transportable but also amenable to being transported by marine shipments, which are the cheapest transport mode. The region is preparing itself to become a hub of green hydrogen production and exports, combining the better of the two renewable energy options.

Our research shows that the potential employment impacts of renewable energy for MENA are multifaceted and promising (Kubursi and Abou Ali, 2024). Embracing renewable energy technologies presents an opportunity for the region to diversify its economy, mitigate the possible negative impacts of digitalisation and artificial intelligence on existing jobs, reduce its carbon footprint and create significant levels of employment across various sectors.

By investing in renewable and green energy infrastructure, R&D, local manufacturing, clean energy intensive manufacturing, energy efficiency measures, and skills development, the region can unlock the full potential of the green energy sector, leading to a greener future and a more sustainable, efficient, diversified and well-paid workforce.

Actual and projected employment impacts of energy production by type of fuel in six MENA countries and the region as a whole

Although there are a few references that can be used to estimate the potential future employment generation capacity of renewable energy in the MENA region, only the employment elasticity coefficients generated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are used here. That choice is based on five advantages over other parameter estimates (see Kubursi and Abou Ali, 2024).

First, the coefficients are presented for all types of energy inputs, a fact that allows the estimation of gross and net employment impacts. For example, the use of the elasticity of 1.5 associated with solar PV per GWh generates the gross employment impacts of solar PV (Kim and Mohammad, 2022). Given that the employment elasticity coefficient per GWh of natural gas is 0.21 means that it is possible to estimate the net employment elasticity coefficient of solar PV. This is equal to 1.29 calculated by subtracting the employment elasticity of natural gas from that of solar PV. Thus, (1.5 – 0.21) is the estimate of the net employment elasticity of solar PV when it is assumed that solar PV will displace natural gas in electricity generation.

Second, the coefficients include the indirect and at times even the induced effects while other similar estimates often include only the direct effects. Third, the coefficients take into account a large set of countries at different stages of development that have made different strides into renewable energy, whereas the other contending estimates are only for a particular region at a particular time and may therefore be inappropriate to represent the expected future employment generating potential of renewable energy in the region. Fourth, the coefficients include the employment generation capacity on realised energy efficiency, which most other studies have excluded. Fifth, the employment generating potential of the coefficients takes into account most of the value chains involved in generating electricity such as construction, installation, manufacturing and operations, and maintenance.

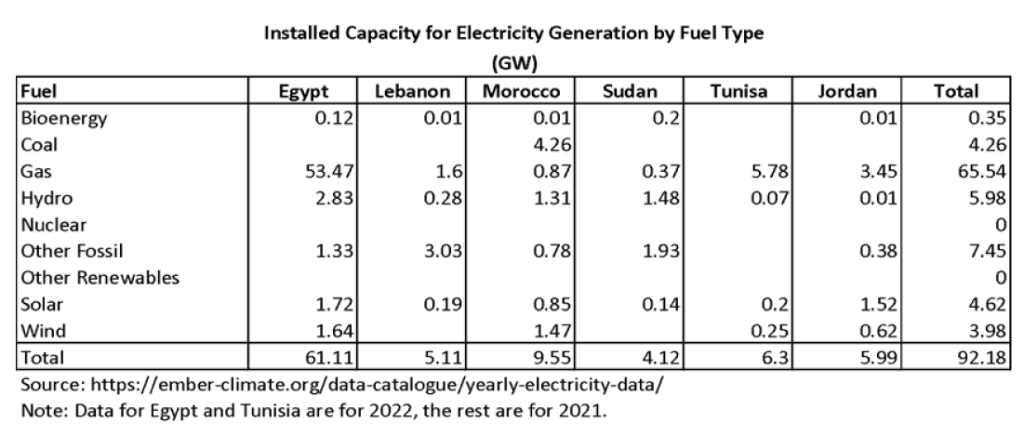

Table 1

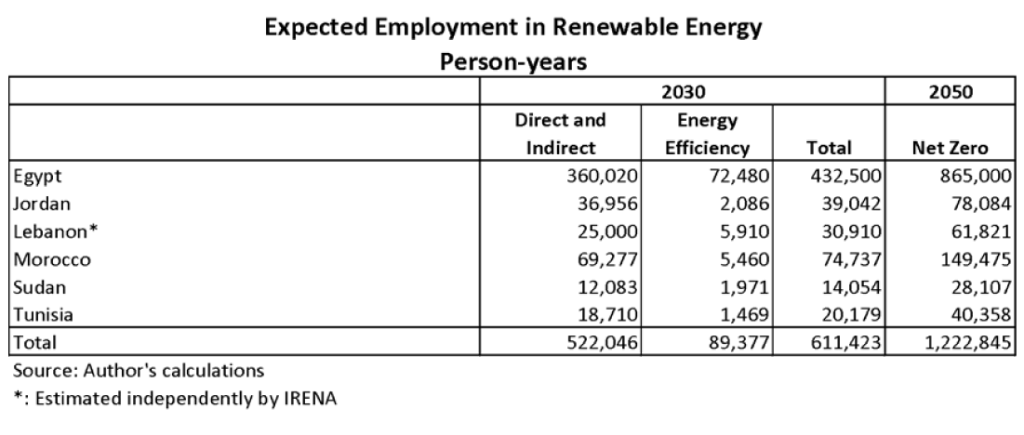

A total of 1.2 million jobs can be generated in the six countries from simply increasing the share of renewable energy in electricity generation to 30%. These employment figures in Table 2 are gross employment estimates with 611,423 person years in 2030 and 1,222,845 in 2050.

Net total employment that takes into account that renewable energy will displace an equal share of that electricity generated by natural gas will be about 525,824 person years in 2030 and 1,051,647 person years in 2050. This need not be the case as renewable energy can be thought of as fully incremental and, in that case, the entire 1.22 million person years could be the expected employment sustained by the renewable energy in the six countries.

The employment generation capacity of energy efficiency is not large, but it will still contribute a total of 89,377 in 2030 and almost twice this level in 2050 when the share of energy efficiency is 30% of total energy generated.

Table 2

When the entire region is the focus of estimating the total employment that could be generated and sustained by a 30% share for renewables in total energy supply in 2030, a large total emerges of about 2,539,384 person years in 2030 and over 5,076,728 person years in 2050 (This is the sum of the direct, indirect and induced employment values in 2050 for renewable energy.). These figures are the total employment generation capacity of both generation of electricity including all of the value chains involved and from realised efficiencies.

The employment projections indicate a massive increase in employment generation capacity, particularly against the backdrop of the high unemployment rates characterising the region. But these estimates pale in comparison to the expected employment generation capacity once we include the opportunities that renewable energy have engendered as the region opened the gates for viable and highly productive EV production.

Already Morocco is producing a million EVs, Saudi Arabia has partnered with Lucent industries and is targeting a similar volume, the UAE has teamed with a Chinese firm that is currently producing 55,000 vehicles that could ramped up to multiples of this volume, and Egypt is on course to produce a large number of EVs for home use and exports. It is not possible to believe that these opportunities could have existed without renewable energy and a determination of MENA countries to realise their emissions reduction commitments under the Paris Protocol.

We are at the cusp of a new employment potential that the region can realise once plans are achieved or exceeded. The potential is there, but it will take commitment, political will, adequate infrastructure, financial resources, skills development, and regional and international cooperation.

Further reading

Kim, Jaden, and Adil Mohammad (2022) ‘Jobs Impact of Green Energy’, IMF Working Papers WP/22/101.

Kubursi, Atif, and Hala Abou-Ali (2024) ‘Potential Employment Generation Capacity of Renewable Energy in MENA’, ERF Policy Research Report No. 47.

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.