In a nutshell

The magnitude of the costs of CBAM for exporters to the EU will differ according to the type of exports and the relative importance of the EU market; initially, the most affected exporting countries will be those where cement, iron, steel, fertilisers and aluminium represent a major share of their exports.

There is likely to be a huge impact for countries like Egypt, where the total exports to the EU of CBAM-covered goods in 2022 – worth approximately €4.6 billion – accounted for about 10% of the country’s total exports to the world.

Arab countries should pursue measures to lessen the CBAM’s impact, including negotiating with the EU on financial and technical assistance; but also act pragmatically on their production processes, for example, enhancing the production and usage of renewable energy.

Over the past few years, the European Union (EU) has sought to raise its climate ambitions through the European Green Deal, a package of policy initiatives aiming to make the continent neutral in terms of carbon emissions by 2050. A central element of that package is the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), a trade policy measure intended to reduce ‘carbon leakage’, where emissions reduction in one part of the world leads to higher emissions elsewhere.

Implementation of the CBAM began on 1 October 2023 with a transitional period, in which exporters to the EU in six carbon-intensive industrial sectors (cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity and hydrogen) are only required to meet reporting requirements – that is, to report their emissions data to the EU registry.

From 1 January 2026, exporters to the EU will be required to purchase CBAM certificates to cover the carbon price difference between non-EU and EU products (Buylova and Nasiritousi, 2024). The full implementation of CBAM is likely to take place in 2034 (Accountancy Europe, 2024; Mitsui and Co., 2023).

The announced aim of the CBAM is to avoid carbon leakage where emissions, including those embedded in imports, can be priced following the certificate prices in the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS), which covers direct and (in some cases) indirect emissions during the production process. The desirability of addressing climate change cannot be challenged, but the cost of implementing it for exporters to the EU could be unprecedented.

The magnitude of such costs will differ according to the type of exports, the state of development of the exporting country and the relative importance of the EU market (UNCTAD, 2021). In the first stage of CBAM implementation, the most affected exporting countries will be those where cement, iron, steel, fertilisers and aluminium represent a major share of their exports. Following those commodities will be chemicals and polymers by the end of 2025, while crude oil, petroleum products and all other EU ETS products are considered for 2030 (Holzhausen and Zimmer, 2020; Mitsui and Co., 2023).

There are likely to be considerable implementation difficulties with the mechanism. But the analysis here focuses on the potential impact on Arab countries based on the EU imports absolute CBAM exposure by country. Out of the top 24 countries in the world likely to be affected, eight are Arab countries – namely Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – and to a lesser extent, Bahrain, Libya, Oman and Tunisia (Holzhausen and Zimmer, 2020).

What is the expected impact on Arab countries from imposition of the CBAM and what are the likely scenarios for overcoming its negative consequences?

Breaking this down, the first important question is the extent of exports as a percentage of total exports from Arab countries from such products, and the extent to which the EU represents a major importer of such products. The next question is the size of the adjustment costs associated with applying such measures in terms of extra costs whether paid as a levy to the EU or undertaken domestically.

On the first question, anecdotal data signal a huge impact for countries like Egypt, where the total exports to the EU of CBAM-covered goods in 2022 – worth approximately €4.6 billion – accounted for about 10% of the country’s total exports to the world. This is a very large portion.

Other Arab Gulf countries, which are major exporters of petroleum and petroleum-related products are likely to be more affected by 2030 (Mitsui and Co., 2023). For example, in aluminum, 85% of EU imports comes from ten exporters, including the UAE and Bahrain, each representing 8% and 3% of such imports. In addition, Oman, Qatar and Saudi Arabia appear on the list of the top 30 exporters to the EU.

With fertilisers, 85% of EU imports are accounted for by five countries, including Algeria and Egypt. Moreover, Libya, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia appear on the list of the top 30 exporters to the EU. For cement, Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia are among the top exporters, accounting for about 80% of total EU imports. Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the UAE also appear on the list of top 30 exporters of cement to the EU. Finally, for steel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and the UAE appear on the list of the top 30 exporters to the EU (Van Bael and Bellis, 2021).

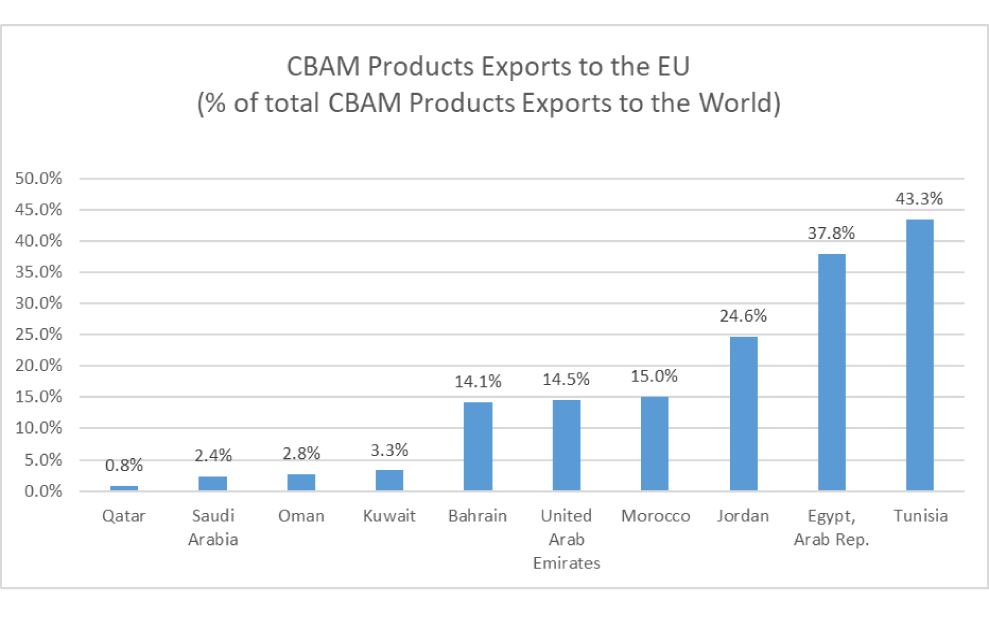

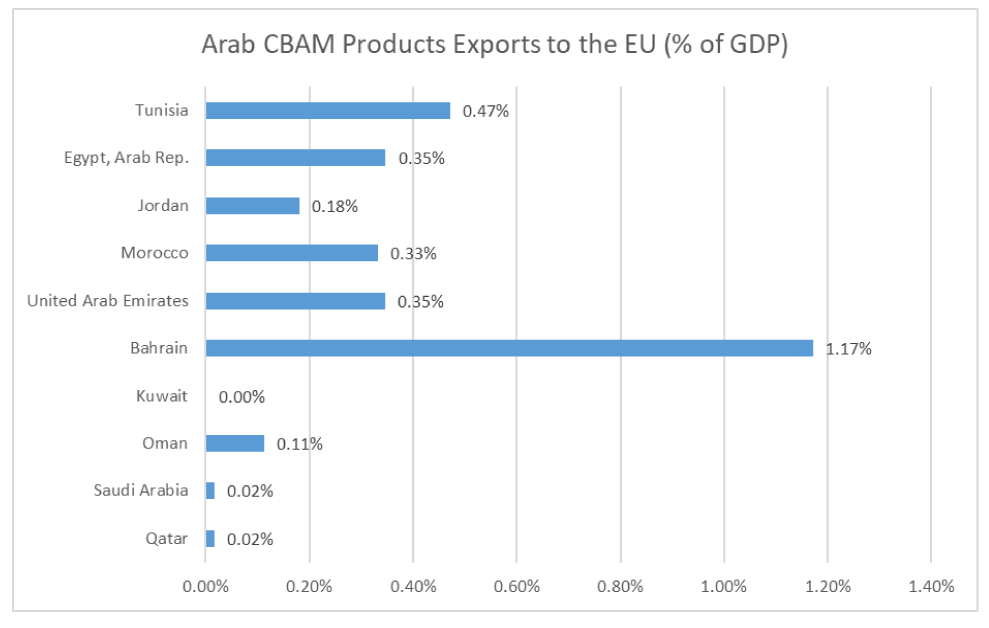

The Relative CBAM Exposure Index developed by the World Bank indicates that all these Arab countries are likely to be significantly negatively affected as percentage of total exports and as percentage of GDP (this is, only related to the five sectors in the first batch) – see Figure 1.

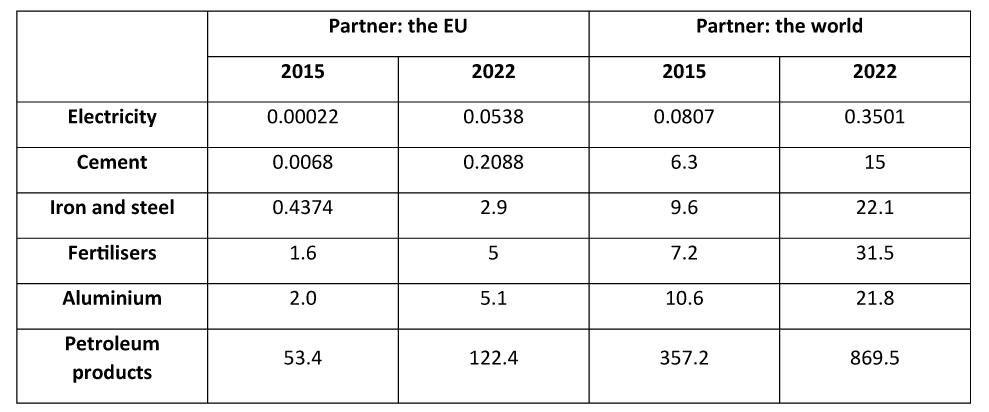

The estimated additional cost due to the CBAM’s introduction is €80 per tonne of carbon, with an expected range of €100-150 by 2030 (Accountancy Europe, 2024). Hence, it is safe to argue that the trade of Arab countries with the EU is likely to be negatively affected, while the reduction of carbon emissions, based on empirical evidence in other incidents, will not necessarily be reduced (UNCTAD, 2021). Table 1 shows the value of Arab exports of the five main CBAM-targeted products to the EU and the whole world. Two main issues arise from these data. The first is associated with the rate of increase of Arab exports to the EU market between 2015 and 2022 in all products; and the second is associated with the relatively high concentration of Arab exports to the EU when compared with the rest of the world for some of those products, namely aluminium and, to a lesser extent, fertilisers.

Table 1: Volume of the Arab region’s exports of CBAM products (billions of US dollars)

Figure 1: Arab countries’ CBAM product exports to the EU as percentage of total CBAM product exports to the world

Figure 2: Arab CBAM products exports to the EU as percentage of GDP

The CBAM’s effects are huge in terms of magnitude when considering the direct costs. Yet there are also additional indirect costs associated with the likely trade retaliation effects by major trading partners such as China and the United States, especially given that the compatibility of the CBAM with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules and regulations is still subject to great deal of uncertainty, and these countries have revealed their discontent with the EU’s CBAM decisions (Chase and Pinkert, 2021).

If such main trading partners undertake retaliatory measures, protectionism could reach new levels and result in additional costs to Arab countries, including spreading to other sectors, not only those with high carbon content (Overland and Sabyrbekov, 2022). This is an issue that should not be neglected when considering the likely effects on Arab countries’ exports to the whole world.

Diverting to other markets is not always an easy option. Standards, transport costs, replacing other competitors and fears of retaliation all act as potential impediments. Even if diversion of trade were successful, it might not be the optimal solution from a welfare perspective (see, for example, African Climate Foundation and the LSE, 2023).

Arab countries should pursue measures to lessen the impact of the CBAM. Negotiating with the EU to reduce its negative effects could include requests for financial and technical assistance. But it is unlikely that negotiations aimed at postponing imposition of such measures or excluding Arab countries can be considered.

Hence, it is advisable for Arab countries to think in a pragmatic manner and start introducing supply-side measures into their production processes. Such measures could include introducing and establishing carbon credit markets, enhancing the production and usage of renewable energy, expanding the production of green hydrogen, and adopting the necessary institutional and regulatory measures to enhance the readiness of the shift to the new system.

Further reading

Accountancy Europe (2024) ‘Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) Combating Carbon Leakage in the EU Factsheet’.

African Climate Foundation and the LSE, London School of Economics and Political Science (2023) ‘Implications for African Countries of Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism in the EU’.

Buylova, Alexandra, and Naghmeh Nasiritousi (2024) ‘CBAM: Bending the carbon curve or breaking international trade?’, European Policy Analysis, Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies.

Chase, Peter, and Rose Pinkert (2021) ‘The EU’s Triangular Dilemma on Climate and Trade’, Policy Brief, The German Marshall Fund of the United States.

Holzhausen, Arne, and Markus Zimmer (2020) ‘EU Climate Policy Goes Global’, Allianz Research.

Mitsui and Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute (2023) ‘Middle East and North Africa Under Pressure to Prepare for CBAM in Two and Half Years – Efforts in Turkey and Egypt’.

Overland, Indra and Rahat Sabyrbekov (2022), ‘Know your opponent: Which countries might fight the European carbon border adjustment mechanism?’, Energy Policy 169 (2022) 113175.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2021) ‘A European Union Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: Implications for developing countries’, UNCTAD.

Van Bael and Bellis (2021) ‘The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism in Seven Questions for MENA Industries’.

World Bank (2023) Relative CBAM Exposure Index (worldbank.org).

The work has benefited from the comments of the Technical Experts Editorial Board (TEEB) of the Arab Development Portal (ADP) and from a financial grant provided by the AFESD and ADP partnership. The contents and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFESD (on behalf of the Arab Coordination Group) nor the ERF.