In a nutshell

A sharp rise in the nominal stock of debt in MENA oil importers and exporters in 2020 stemmed from both pandemic support spending and lower fiscal revenues; oil-exporting countries in the region quickly reined back their primary deficits, but oil importers did not.

Over the past decade, oil-importing countries in MENA have been unable either to inflate or grow their way out of high and rising levels of public debt: episodes of higher growth or higher inflation have coincided with faster debt accumulation, which pushes the public debt-to-GDP ratio back up.

GDP growth can ease indebtedness, but it must come hand in hand with fiscal discipline, including curbing extra-budgetary expenditures; improving the quality and availability of data will not only serve debt transparency, but also help to mitigate uncertainty.

Our April 2024 MENA economic update – Conflict and Debt in the Middle East and North Africa – strikes a sombre note. The conflict centred in Gaza has resulted in a massive loss of life, unprecedented destruction of infrastructure and forced displacement. Over 1.7 million people, three-quarters of the population of Gaza, are internally displaced.

A devastating humanitarian crisis has unfolded with widespread food and water insecurity. At least one in four Gazans is experiencing catastrophic hunger. Cumulative impacts on physical and mental health have hit women, children, older people and those with disabilities the hardest, with children anticipated to be facing life-long consequences for their development.

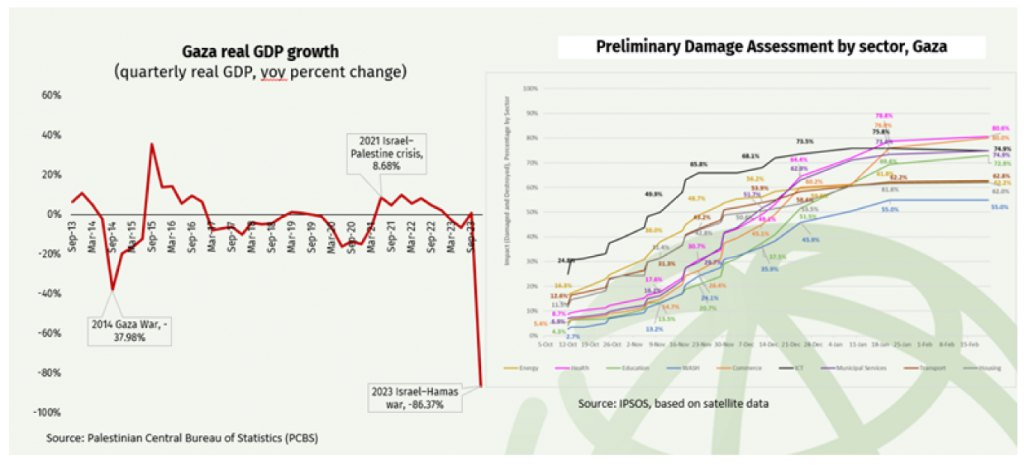

In the fourth quarter of 2023, real GDP in the Gaza Strip was 86% lower than it was in the final three months of 2022 (see Figure 1). Real GDP contracted by roughly 25% in 2023, which is comparable to some of the worst periods of conflict in recent history. The May 2024 World Bank Economic Monitoring Report on the Impacts of the Conflict in the Middle East on the Palestinian Economy provides a more recent assessment.

Figure 1: GDP growth and damage in Gaza

The regional economic effects of the war have so far been modest, on average, and marked by severe variability in magnitude, mostly depending on the proximity to the conflict and the socio-economic relations with the West Bank and Gaza. As for the future, regional impacts will continue being a function of the conflict’s potential escalation and/or duration.

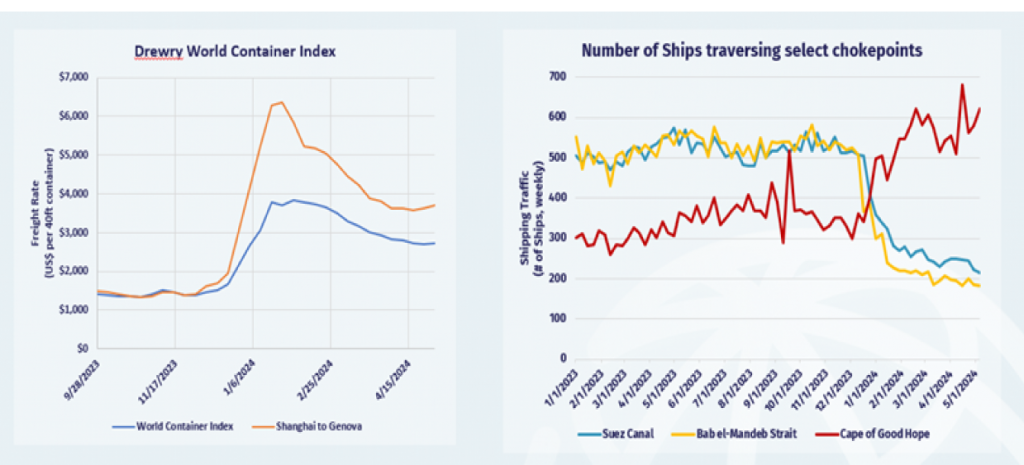

One key channel of impact has been tourism, especially in countries neighbouring the conflict. International trade was affected by Houthi attacks on commercial ships which reduced traffic through the Bab El-Mandeb strait and the Suez Canal. Spot rates for container shipping have gone up globally in the immediate aftermath of the conflict, and especially for routes from the East to Europe, but these rises have not translated into increased consumer prices spikes (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Effects of the conflict in the Middle East on trade

The conflict in the Middle East is taking place in a global economy that is in its third consecutive year of growth deceleration. Emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs), excluding MENA, are expected to grow by around 4.4% in 2023 and 3.9% in 2024, while inflation and oil prices trend downward. After muted growth in 2023, GDP in the MENA region is forecast to grow by 2.7% in 2024. MENA oil exporters and importers are expected to grow at similar rates.

There is broad consensus that the overlapping crises that have recently hit the global economy have increased uncertainty, making policy-makers’ jobs harder. To quantify this, a widely used proxy for uncertainty is the level of disagreement among economic forecasters – as measured by the dispersion of individual forecasts (see Figure 3).

By this measure, uncertainty spiked across the board following the outbreak of the global pandemic, but began to moderate at the end of 2021. Uncertainty has since returned close to pre-pandemic levels in EMDEs and high-income countries and it is once more below that of MENA, where instead it has remained high.

Figure 3: Indicators of uncertainty in EMDEs, including MENA

The uncertain prospects for the region, exacerbated by the conflict, add to pre-existing vulnerabilities, one of which is high public debt-to-GDP ratios. On average, over the past half century, armed conflict has been associated with slowing growth and rising public debt (Fan et al, 2024). The same could happen in the Middle East if the current conflict were to expand.

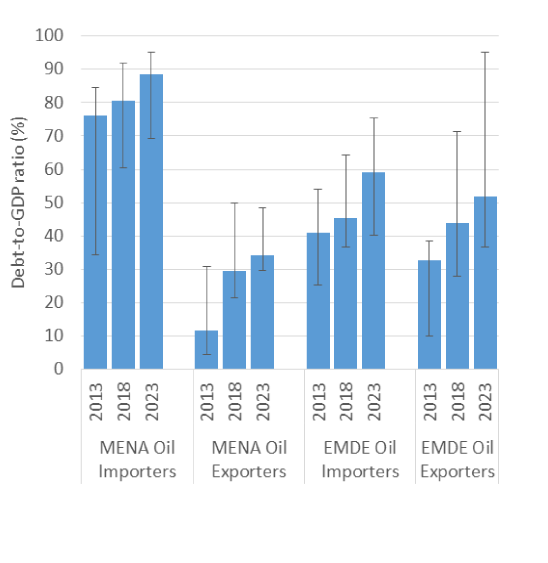

Over the past ten years, debt-to-GDP ratios in EMDEs, including those in MENA, have increased from about 40% to almost 60% of GDP (see Figure 4).

High debt-to-GDP ratios can have important economic consequences. When governments borrow, they may crowd out private sector investment because rising interest rates may increase the cost of capital for the private sector.

In addition, high levels of debt may be accompanied by costly interest payments that gradually reduce the ability of governments to make other growth-enhancing public investments. Moreover, the effect of additional fiscal spending on GDP – what is known as the fiscal multiplier – is smaller when public debt is high.

Figure 4: Debt-to-GDP ratios in MENA and EMDE oil exporters and importers

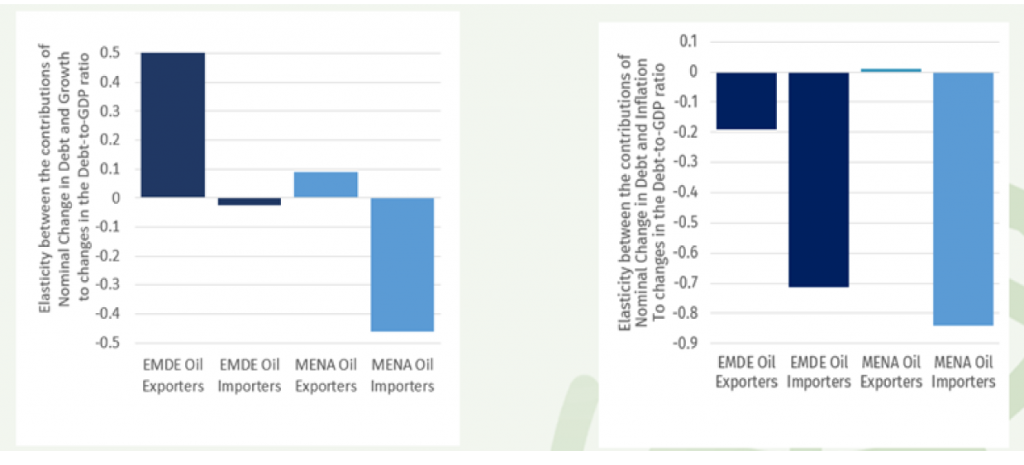

To shed light on the factors behind the recent rise in debt-to-GDP ratios among MENA countries, the Conflict and Debt in the Middle East and North Africa report uses an accounting framework that breaks down changes in debt-to-GDP ratios into three broad components: first, nominal changes in gross debt; second, real GDP growth; and third, inflation, as captured by changes in the GDP price deflator. In turn, the first component – changes in debt – is further decomposed into subcomponents related to the government’s fiscal balance and to changes in the value of pre-existing debt and other factors.

The sharp rise in the nominal stock of debt that occurred in MENA oil importers and exporters in 2020 stemmed from a sizeable increase in primary deficits. Expressed as a percentage of the previous year’s GDP, primary deficits were more than three times larger in 2020 than in 2019 or 2018. The increase in nominal debt stocks that year is likely to reflect both pandemic support spending and lower fiscal revenues.

MENA oil exporters quickly reined back their primary deficits in 2021 and although nominal debt stocks continued to increase, they did so at a much lower rate than in the previous year. In contrast, the large primary deficits of MENA oil importers in 2020 persisted into 2021. Moreover, despite decreasing in 2022 and 2023, the primary deficit of MENA oil-importing countries remained twice as large as in 2018 and 2019.

Two strategies to such circumstances that are widely discussed in the public domain are growing out of debt and inflating it away. But oil-importing economies in MENA have been unable to ‘grow out of debt’ or ‘inflate debt away’.

On their own, real GDP growth and inflation can bring down the debt-to-GDP ratio. But MENA oil-importing economies have found it harder to do so because over the past ten years, episodes of higher growth or higher inflation have coincided with faster debt accumulation, which pushes the debt-to-GDP ratio back up. For every additional percentage point decrease in the debt-to-GDP ratio attributable to real GDP growth, almost half is offset by increasing nominal debt stocks (see Figure 5).

This contrasts with other oil-importing EMDEs, where this offsetting pattern is absent. In oil-importing economies in MENA, GDP growth did not reduce debt-to-GDP ratios largely because of extra-budgetary factors and of the effect of exchange rate fluctuations on the value of debt denominated in foreign currencies.

Figure 5: Impacts of growth and inflation on debt-to-GDP ratios in MENA and EMDE oil exporters and importers

Recent spikes in inflation are unlikely to have alleviated the debt burden for MENA oil importers. For every percentage point decrease in the debt-to-GDP ratio attributable to inflation, almost all of it – more than 80% – is undone by increases in the nominal quantity of debt. Again, the key drivers behind this are the effects of exchange rate fluctuations, which have been substantial in a country like Egypt, and other extra-budgetary factors such as off-budget expenditures and asset accumulation.

Oil importers in the MENA region have little room for manoeuvre if significant economic threats were to appear. They are borrowing against an uncertain future. Their inability to grow out of debt over the past ten years is a further reason for concern.

Even worse, in many countries, the degree of debt vulnerabilities is obscured by extra-budgetary outlays. GDP growth can ease indebtedness, but it must come hand in hand with fiscal discipline, including curbing extra-budgetary expenditures. Improving the quality and availability of data will not only serve debt transparency, but also help to mitigate uncertainty, which historically has been high in MENA.

Further reading

Fan, RY, D Lederman, H Nguyen and CJ Rojas (2024) ‘Calamities, Debt, and Growth in Developing Countries’, IMF Economic Review 72: 487-507.

World Bank (2024) Note on the Impacts of the Conflict in the Middle East on the Palestinian Economy.