In a nutshell

Growth in the Middle East and North Africa is forecast to experience a sharp deceleration in 2023, bringing to an end the diverging growth patterns observed between oil exporters and oil importers in the region – what some called ‘A Tale of Two MENAs’.

The global shocks that hit the region in 2020-22 resulted in over five million more people becoming unemployed above the already high levels of unemployment that characterised the region even before the Covid-19 pandemic hit.

With negative shocks, labour demand falls and there is a trade-off between more unemployment and lower real wages; while neither is desirable, the policy implications are clear: real wage flexibility coupled with targeted cash transfers are the best way to reduce the long-term costs facing families.

The Arab Spring. Armed conflict. Rising public debt. Sovereign default. Covid-19. The Russian invasion of Ukraine. Inflation. Rising interest rates. Oil price volatility. Natural disasters. While these shocks are expected to be temporary, will they permanently scar the MENA region’s most precious resource, its people?

A new report – Balancing Act: Jobs and Wages in the Middle East and North Africa When Crises Hit – answers this question by highlighting the trade-offs facing labour markets in the aftermath of macroeconomic shocks. After analysing the region’s macroeconomic prospects, the October 2023 edition of the MENA Economic Update assesses the human toll of macroeconomic shocks in terms of lost jobs and deteriorating livelihoods. It provides one of the first systematic analyses of labour market adjustments to shocks in the region.

MENA is forecast to experience a sharp deceleration in growth in 2023. Successive oil production cuts from OPEC+ members combined with relatively low oil prices compared with mid-2022 have brought an end to ‘A Tale of Two MENAs’ – the diverging growth patterns observed between the developing oil exporters and members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) on one hand, and developing oil importers on the other.

Forecasts for growth in the region at the time of the new report’s publication on 5 October averaged 1.9% in 2023, down from 6% in 2022. This deceleration is most marked among GCC countries, where growth in 2023 is projected to average 1%, considerably less than the 7.3% in 2022.

Improvements in the livelihoods of people in the region depend on growth in income per capita, which at the time of the report’s publication was forecast to decelerate in the region as a whole from 4.3% in 2022 to 0.4% in 2023. The slowdown is pervasive across country groups, but it is more marked among oil exporters. By the end of 2023, the authors estimate that only eight out of 15 MENA economies will have returned to their pre-pandemic level of real GDP per capita.

In the current economic context – which is marked by heightened volatility in terms of trade stemming from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a global surge in interest rates, currency depreciations and inflationary pressures – the report underscores the long-lasting impacts of even transitory macroeconomic shocks. It is a reminder to keep sight on what matters: the livelihoods of the people of the region.

When contrasting labour market adjustments in MENA with those in other emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs), the report shows that, by and large, labour markets in MENA and other EMDEs adjust to shocks in similar ways. This evidence challenges the prevailing notion that labour markets in MENA are fundamentally distinct from the global landscape.

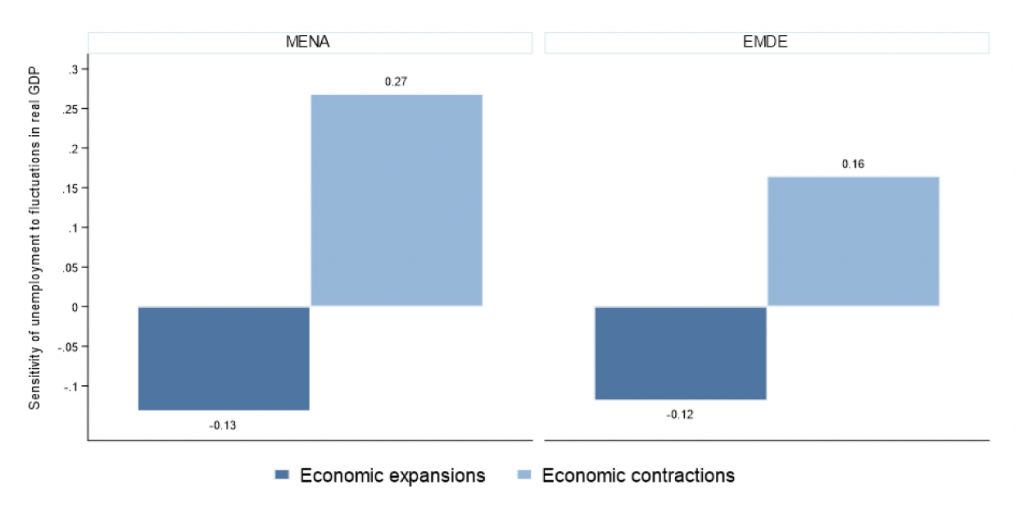

But labour market dynamics in MENA differ in one critical dimension: during economic downturns, the response of unemployment in MENA is nearly double that of other EMDEs (see Figure 1). In other words, when negative shocks strike labour markets, the consequence is a higher number of unemployed people in MENA compared with their counterparts in other EMDEs.

The authors estimate that the macroeconomic shocks of 2020-22 led to an additional 5.1 million individuals becoming unemployed in MENA. If MENA exhibited the same responsiveness of unemployment to negative shocks as other EMDEs, the cumulative effect during 2020-22 would have been 2.1 million fewer unemployed individuals.

Figure 1: The response of unemployment to fluctuations in real GDP in MENA and EMDEs

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the International Labour Organization.

When economic shocks strike without triggering inflation, it is unemployment that takes centre stage as the primary margin of labour market adjustment in MENA. Whether it is the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic or the impact of adverse shocks to the terms of trade, the report underscores that in the MENA region, these shocks can potentially lead to an increase in the number of individuals finding themselves unemployed.

The COVID-19 MENA monitor surveys conducted by the ERF in November 2020 show that 29% of wage workers in Morocco and Tunisia reported experiencing a permanent or temporary layoff, but only 15% reported a decline in pay. Evidence from Iran also suggests that following the global decline in oil prices in 2014-15, which led to a decline in aggregate demand and downward pressure on prices, unemployment rate rose by around 5% in the quarter following the shock and by up to 15% three quarters later.

On the other hand, when economic shocks trigger inflation, unemployment may be less responsive but real incomes fall. For example, following large currency devaluations, workers may find themselves sheltered from unemployment, as employment levels remain relatively stable. But their purchasing power declines as a result of the drop in their real incomes.

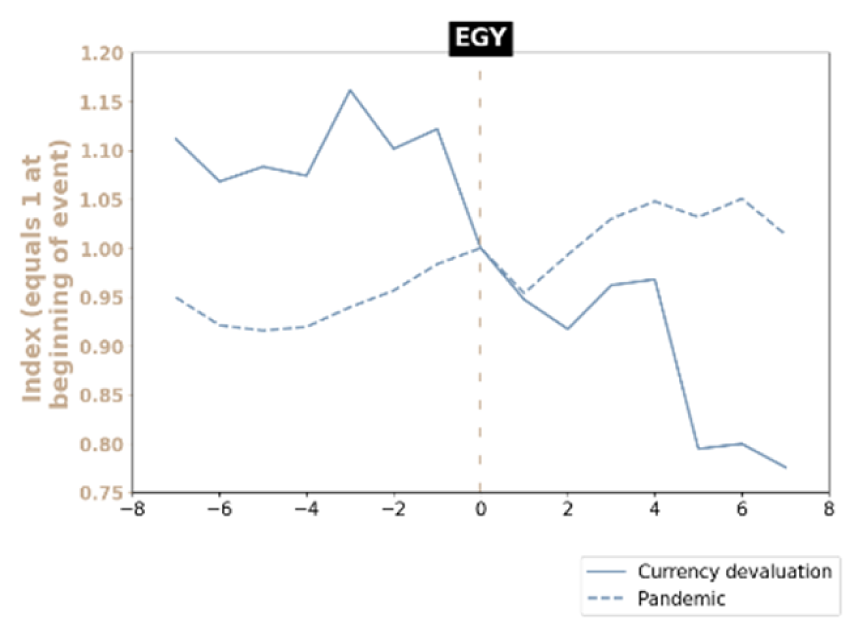

This type of adjustment took place after the 2016 currency devaluation in Egypt. Following the decision of the Central Bank of Egypt to end foreign exchange controls and the managed float regime on 3 November 2016, the Egyptian pound went into a steep depreciation. This led to inflation of 30% in 2017. Unemployment rates did not surge. Instead, over the following six months, real wages declined by 10%. Fifteen months after the currency depreciation, real wages had fallen by 20% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Real monthly wages following Egypt’s 2016 currency devaluation and the pandemic

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Labor Force Surveys.

The balancing act of the new report’s title involves navigating the trade-offs in the labour market when an economy confronts economic shocks that lead to a decrease in labour demand. One critical trade-off is the decline in employment and the decrease in real wages in inflationary environments, neither of which is desirable. Temporary job losses can have long-term negative repercussions for workers – what is referred to in economic research as labour scarring (see, for example, Ruhm, 1991; Jacobson et al, 1993; Pissarides, 1992; Kroft et al, 2013; Arias and Lederman, 2023) – and the erosion in real wages has dire implications in terms of standards of living and income inequality.

During macroeconomic shocks, the policy challenge is to balance the risks of declines in employment against the risks of declines in real wages. Even temporary job losses can have long-lasting negative consequences. In Egypt, for example, men who were involuntarily displaced from their work due to firm shutdown or job termination by the employer have a greater likelihood of remaining unemployed or of being informally employed even 10 years post-job displacement.

The short-term erosion of real wages by high inflation raises different challenges. As highlighted in the April 2023 MENA Economic Update, the poorest households typically experience higher levels of inflation than the richest households, a difference that has dire implications for inequality.

The new report discusses policy options in the face of this balancing act. It highlights the importance of preserving the flexibility of real wages during periods of adverse economic shocks, which can help to reduce job losses, while simultaneously safeguarding the vulnerable segments of the population through well-targeted cash transfer programmes.

Further reading

Arias, F, and D Lederman (2023) ‘Plant Closings and the Labor Market Outcomes of Displaced Workers: Evidence from Mexico’.

Gatti, R, D Lederman, N Elmallakh, J Torres, J Silva, R Lotfi and I Suvanov (2023) Balancing Act: Jobs and Wages in the Middle East and North Africa When Crises Hit, MENA Economic Update, October 2023, World Bank.

Jacobson, LS, RJ LaLonde and DG Sullivan (1993) ‘Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers’, American Economic Review 83(4): 685-709.

Kroft, K, F Lange and MJ Notowidigdo (2013) ‘Duration Dependence and Labor Market Conditions: Evidence from a Field Experiment’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(3): 1123-67.

Pissarides, CA (1992) ‘Loss of Skill During Unemployment and the Persistence of Employment Shocks’, Quarterly Journal of Economics (107(4): 1371-91.

Ruhm, CJ (1991) ‘Are Workers Permanently Scarred by Job Displacements?’, American Economic Review 81(1): 319-24.