In a nutshell

Poverty is a complex and interconnected policy challenge which requires a broad suite of interventions.

Policy-makers in the Arab region should recognise that reforms must take into account the various ways in which different dimensions of deprivation interact with one another.

Innovative policy solutions should rest on an understanding of this complexity, while acknowledging that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution for fighting poverty in the Arab region.

There are many factors that affect poverty levels. This makes measuring poverty challenging, and means that a variety of methods need to be used. Important as it may be, the money metric approach to poverty is a narrow lens to view such a complex and multidimensional phenomenon. Recognising the importance of this insight, Arab countries have commissioned the League of Arab States (LAS) and several UN agencies to prepare the Second Arab Multidimensional Poverty Report. The report adopts a regional Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), which reflects more directly the experiences and multiple overlapping deprivations of the poor in Arab countries. To design effective policies to combat poverty, accurate measurement is a crucial first step.

The report’s method is backed by institutions around the world. Among the proponents of the multidimensional approach is the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, which, along with ESCWA, have proposed a revised Arab MPI that builds on the conceptual framework used in the first report and embraces Amartya Sen’s capability approach, all while being guided by recent developments in multidimensional poverty research. As researcher’s understanding of the origins and effects of poverty change, so too should the methods for analysing potential policy interventions.

Better measurement is the route to better policy, and this gives governments in the Arab region the opportunity to keep improving people’s lives. The revised MPI offers a more regional perspective. This helps to better capture the manifestations of moderate poverty in middle-income Arab countries. To this end, the new method focuses on moderate levels of deprivation in its structure, dimensions and indicators. In terms of the index’s structure (and based on a wide consultation process), the main innovation in the revised Arab MPI is its assessment of poverty in both material and social capability spaces, giving both pillars equal importance. Social capabilities include health – child mortality, nutrition and early pregnancy – as well as education – school attendance, age-schooling gap and adult education. Material capabilities include housing, access to services of water, sanitation and electricity, and assets for communication, mobility and livelihood. Arab countries have witnessed progress in social wellbeing but less so in material and living-conditions wellbeing, hence this normative stance. This is reflected in the adoption of the equal weighting scheme between the two pillars.

Poverty levels across Arab countries with different income levels

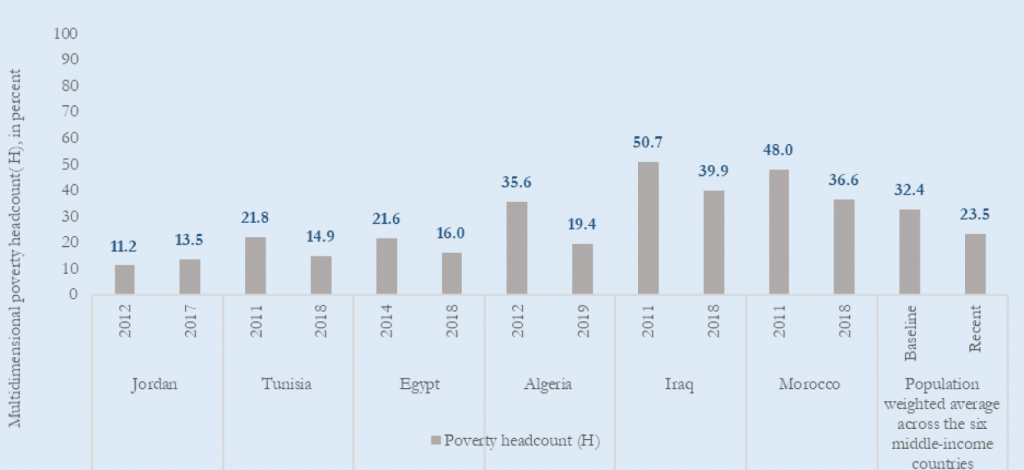

The report has some good news and some bad news. The good news is that many middle-income Arab countries managed to reduce multidimensional poverty over the past decade (Figure 1). The bad news is that one in four people in these countries was multidimensionally poor in 2019. The report also finds that educational deprivations are the most important challenge facing these countries, followed by deprivation in living conditions (including asset ownership indicators which are closely related to household income and expenditure). The other piece of bad news is that multidimensional poverty is significantly higher in less developed countries (or LDCs), especially in conflict-affected countries within the Arab region.

Figure 1: Multidimensional poverty headcount ratio in Arab middle-income countries over time

Source: Second Arab Multidimensional Poverty Report (ESCWA, LAS, UNICEF, UNDP, UNFPA and OPHI, 2023)

Innovative policy solutions

Three things need to be done. First, policy-makers need to recognise that actions to reduce income poverty will not always reduce multidimensional poverty. So, reducing poverty faster will mean playing it smart with public policy. Right now, many Arab countries focus on making cash transfers to the income poor as a main pillar of their poverty reduction strategy. But this needs to change. Interventions need to target income and multidimensional poverty at the same time.

Can this be done? Yes, but it won’t be easy. For example, cash transfers might help a poor family headed by a single mother make ends meet. But if the state also provides her with access to a close by and affordable nursery, this might empower her to find a job with higher and more sustained income. If that nursery offers a subsidised balanced diet to her child, this might significantly reduce the possibility that the child will suffer from malnutrition or stunting. So, poverty reduction efforts, whether income or multidimensional, require a concerted and coordinated effort from multiple line ministries and partners, not just one entity. A joined-up approach is vital.

Second, in some countries national efforts alone will not be enough. In Arab LDCs and conflict-affected countries, additional regional and global support is necessary. The good news is that the Arab region has enough resources to foot the bill. According to a recent ESCWA paper, the resources required to close the poverty gap are miniscule when compared with the region’s income and wealth. But eradicating poverty is not only a problem of finding financial resources. There are other critical factors to consider.

This brings us to the third and final recommendation. Arab countries need to reform their governance systems to make their public sectors more efficient in delivering the kinds of support that are needed by the poor. This means (among other things) having more effective delivery of public schooling and health systems, better infrastructure and communications systems, and better targeted public investments. This will enable the private sector to thrive and generate more jobs for the poor. No doubt such institutional reforms will be the toughest part of any policy agenda, but they are necessary to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Finally, it should be noted that unfortunately there are no ready-made international fixes and recipes for making these policy recommendations work. The Arab region will have to draw on home-grown solutions that build on centuries of accumulated wisdom. Fortunately, the region has significant untapped potential, including educated, youthful and passionate future leaders. The challenge is to transform Arab economies and governance systems in a way that allows these potential leaders equal opportunities and spaces for innovative approaches to fighting poverty. This will not only reduce income poverty but will also ensure the region’s trend of improvement in terms of multidimensional poverty reduction is sustained.

Notes:

The Second Arab Multidimensional Poverty Report was prepared by the League of Arab States in partnership with the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Population Fund, (UNFPA), and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI).