In a nutshell

A body of research evidence suggests that revolutions and wars – including the Iranian revolution and the subsequent war with Iraq – tend to result in a significant decrease in the level of income inequality within the country.

Without the regime change from monarchy to the Islamic Republic and the war conditions, the average annual income inequality in Iran would have been approximately nine units higher.

The revolution and war reduced income inequality in Iran by negatively affecting the higher income earners, rather than elevating the bottom income groups.

Open resistance to the Pahlavi monarchy in Iran began in 1977, reached its peak in 1978 and eventually led to the collapse of the regime in February 1979. This resulted in the establishment of the Islamic Republic, with Ayatollah Khomeini as its leader. A year later, in 1980, the devastating war with Iraq began, following the Iraqi invasion of Iran, and lasted for eight years, until 1988. (See Kurzman, 2005, for a comprehensive analysis and timeline of the revolution.)

Several studies have evaluated the economic costs of the Islamic revolution and war with Iraq for Iran. These include Alnasrawi (1986), Amirahmadi (1990), Mofid (1990), and Jahan-Parvar (2016), all of which demonstrate substantial economic damage as a result of regime change and the war with Iraq.

Farzanegan (2022) employs a synthetic control approach to estimate, for the first time in the case of Iran, the income loss or opportunity costs resulting from the revolution and war with Iraq. The estimates show that the average Iranian lost an accumulated sum of approximately US$34,660 during the period 1978-88, with an average annual real per capita income loss of US$3,150.

While these studies measure the economic costs and lost income of Iranians following the revolution and during the war, they do not examine the development of income distribution under the new political regime and war conditions.

Social scientists have recognised that major social revolutions and widespread wars often result in a reduction of income inequality (Scheidel, 2018). Some other scholars have also suggested that revolutions and wars are often the outcome of pre-existing social and economic changes within a society and its governing structure (Beck, 2020). Therefore, it becomes challenging to isolate and examine the specific impact of revolutions on changes in income inequality.

Our recent study (Farzanegan and Kadivar, 2023) addresses this issue by employing a research tool known as the synthetic control method to evaluate the combined effect of the Iranian Revolution and the subsequent Iran-Iraq war from 1980 to 1988 on the country’s income inequality levels.

Our research has three main contributions:

This is the first study using the synthetic control method to examine the impact of revolution and war on income inequality in Iran. Previous studies have applied this method to analyse the effect of events such as the Cuban revolution of 1959 (Jales et al, 2018), the Islamic revolution in Iran (Farzanegan, 2022) and political turmoil such as the Arab Spring (for example, Echevarría and García-Enríquez, 2020) on economic performance measured mainly by GDP.

The distributional effects of regime changes and wars have been understudied. A few studies cover income inequality among other issues and apply the synthetic control method to measure the effects of political regimes, revolution or other shocks. For example, Grier and Maynard (2016) examine the effect of populist government of Hugo Chavez on a set of macroeconomic indicators including Gini, while Lawson et al (2019) study the effect of the (Rose) revolution in Georgia on inequality.

Second, while studies of the effects and determinants of income inequality in post-revolution Iran have been conducted (Farzanegan and Alaedini, 2016; Salehi-Isfahani, 2017), the causal impact of the revolution and war on the distribution of income in Iran remains unexamined. To estimate this effect accurately, we require a counterfactual Iran that mimics factual Iran before the revolution.

Factual Iran experienced revolution and war while its counterfactual does not. The synthetic control method provides us with a means of estimating this counterfactual scenario and investigating the impact of the revolution and war on income inequality in Iran.

Finally, our research contributes to the growing field of quantitative studies on contentious politics in the Middle East, particularly in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. By documenting the impact of contentious politics on income inequality, we expand on this body of work by examining a structural outcome of collective action.

Key results

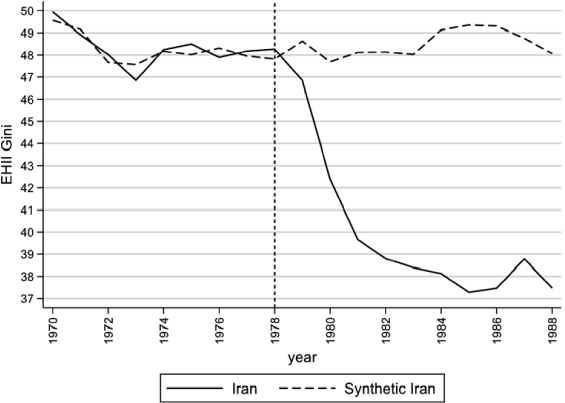

Figure 1 illustrates the trajectory of income inequality in Iran and its counterfactual for the period between 1970 and 1988. The synthetic Iran accurately replicates the pre-revolution income inequality pattern. But post-1978 and during the Iran-Iraq War, the two lines significantly diverge.

The factual Iran experiences a decline in income inequality post-revolution, while the estimated index for the counterfactual Iran remains stable and even increases during the war period. This result supports the findings of previous research that socialist revolutions and wars, including the Iranian revolution and subsequent war with Iraq, result in a significant decrease in the level of income inequality within the country.

Figure 1. Income inequality (EHII-Gini): Iran versus Synthetic Iran.

Note: Estimated Household Income Inequality Data Set (EHII)—is derived from the econometric relationship between UTIP-UNIDO, other conditioning variables, and the Deininger and Squire (1996) dataset. For more details, see Galbraith and Kum (2005).

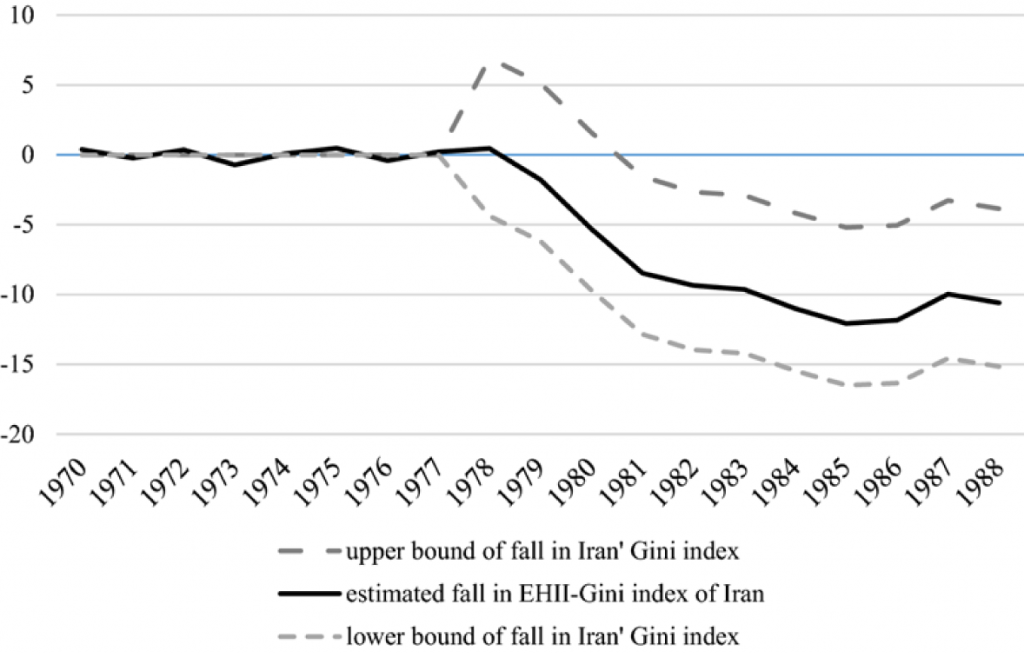

Figure 2 demonstrates the estimated joint effect of the revolution and war on income inequality as the difference between the factual Iran and its counterfactual. Our findings show that during the post-1978 revolution and the war with Iraq, income inequality in Iran was decreased by an average of nine units per year.

This represents a substantial decrease in income inequality, as the standard deviation of the EHII-Gini index in the post-1978 period was 2.97 units. Without the regime change from monarchy to the Islamic Republic and the war conditions, the average annual income inequality in Iran would have been approximately nine units higher.

Figure 2. Income inequality (EHII-Gini) gap between Iran and synthetic Iran (with confidence intervals).

We have conducted several sensitivity tests and employed an alternative measure of income inequality from the Standardized World Income Inequality Database. The impact of the revolution and war on income inequality in Iran remains robust and consistent.

Why did the war and revolution result in a significant reduction in Iran’s income inequality?

Although our data on Iran’s Gini does not permit a quantitative analysis of the underlying mechanisms, we draw on existing accounts of the Iranian economy during this period and relevant data sources to present a qualitative discussion of the drivers of this change.

Our discussion suggests that the revolution and the war reduced income inequality in Iran by negatively affecting the higher income earners, rather than elevating the bottom income groups. Overall, our findings provide valuable insight into the mechanisms shaping income inequality in Iran during this critical period.

Conclusion

Research on the impact of social revolutions and large-scale wars on income inequality posits that these violent upheavals have a reducing effect on levels of inequality within countries. But accurately assessing the independent effect of such events is a challenging task as they often result from sequences of internal political and socio-economic transformations.

To examine this issue, our study focuses on the case of Iran during the 1978-79 revolution and the subsequent war with Iraq. It employs the synthetic control method to estimate the joint impact of these events on changes in the country’s income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient.

Our results show a significant effect of the revolution and war on reducing income inequality. Over the entire 1979-88 period, on average and per year, the Gini index of Iran was reduced by approximately three standard deviations of the index. The results are robust to a series of sensitivity checks.

Finally, this study explores the various drivers behind the reduction of income inequality in post-revolution Iran, suggesting that the impact of the regime change and war conditions was more damaging to the higher income earners.

Further reading

Alnasrawi, A (1986) ‘Economic Consequences of the Iraq-Iran War’, Third World Quarterly 8(3): 869-95.

Amirahmadi, H (1990) ‘Economic Reconstruction of Iran: Costing the War Damage’. Third World Quarterly 12(1): 26-47.

Beck CJ (2020) ‘Revolutions against the State’, in: Janoski, T, C de Leon, J Misra and IW Martin (eds) The New Handbook of Political Sociology, Cambridge University Press.

Deininger, K, and L Squire (1996) ‘A new data set measuring income inequality’, World Bank Economic Review 10: 565-91.

Echevarría CA, and J García-Enríquez (2020) ‘The economic cost of the Arab Spring: the case of the Egyptian revolution’, Empirical Economics 59: 1453-77.

Farzanegan MR (2022) ‘The economic cost of the Islamic revolution and war for Iran: synthetic counterfactual evidence’, Defence and Peace Economics 33: 129-49.

Farzanegan MR, and P Alaedini (2016) Economic Welfare and Inequality in Iran: Developments since the Revolution, Palgrave Macmillan.

Farzanegan, MR, and MA Kadivar (2023) ‘The effect of Islamic revolution and war on income inequality in Iran’, Empirical Economics.

Galbraith JK, and H Kum (2005) ‘Estimating the inequality of household incomes: a statistical approach to the creation of a dense and consistent global data set’, Review of Income and Wealth 51: 115-43.

Grier K, and N Maynard (2016) ‘The economic consequences of Hugo Chavez: a synthetic control analysis’, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 125: 1-21.

Jahan-Parvar, MR (2016) ‘The Cost of a Revolution’, Iran Nameh: A Quarterly Journal of Iranian Studies 30: 78-101.

Jales H, TH Kang, G Stein and RF Garcia (2018) ‘Measuring the role of the 1959 revolution on Cuba’s economic performance’, World Economy 41: 2243-74.

Kurzman C (2005) The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, Harvard University Press.

Lawson R, K Grier and S Absher (2019) ‘You say you want a (Rose) revolution? The effects of Georgia’s 2004 market reforms’, Economics of Transition 27: 301-23.

Mofid, K (1990) The Economic Consequences of the Gulf War, Routledge.

Salehi-Isfahani D (2017) ‘Poverty and income inequality in the Islamic Republic of Iran’, Revue Internationale Des Études Du Développement 1: 113-36.

Scheidel W (2018) The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-first Century, Princeton University Press.