In a nutshell

The Development Challenges Index makes an important shift from development achievements to development challenges; this reverses the narrative to foreground countries that are most rather than least challenged.

Countries with the largest deteriorations in DCI between 2000 and 2020 are mainly in the Arab region and in Latin America and the Caribbean; several of these countries have confronted domestic or regional conflict.

Environmental sustainability or governance challenges make up the highest shares in most regions except sub-Saharan Africa, where quality-adjusted human development challenges are greater.

The capability approach to development offers a comprehensive conceptual framework for analysing challenges and a widely used measure in the form of the Human Development Index (HDI). But since the global development landscape has changed considerably over the past three decades, a change in conventional measurement approaches is now necessary.

Many developing countries have made quantitative achievements on various development goals, but traditional measures have largely overlooked the quality of those achievements. In addition, challenges related to sustainability and good governance have often been dealt with separately from the core human development achievements represented in the HDI’s health, education and income dimensions.

The World Development Challenges Report proposes a new global Development Challenges Index (DCI) to measure development from a broader perspective.

As a first step towards this goal, the DCI adapts the global HDI to reflect the quality of human development achievements, which implies discounting HDI achievements by measures of quality. But the report also goes well beyond that adjustment. Since a broader development measurement framework should entail integrating other dimensions (Jahan, 2022), the report takes up two challenges of fundamental importance at all levels: environmental sustainability and governance.

The case for integrating these aspects is strong. Environmental sustainability is an important operating condition for human development. Sen and Anand (1994) endeavoured to address the integration of sustainability and human development using a theoretical and systematic approach. They argued that sustainability is essentially entwined with intergenerational equity. In the context of the environment, sustainability means that ‘the present generation should strive to preserve the environment in such a fashion as to equitably bequeath comparable human-development benefits to future generations’ (McKinley, 2016).

With wellbeing increasingly realised through advances in human capabilities, it has become more important to emphasise agency, namely, that freedom has an independent and intrinsic worth of its own and an instrumental value in enhancing wellbeing. Exercising agency requires the rule of law, civic political participation, and accountable and efficient institutions.

Without these elements, achievements in health, education and environmental sustainability cannot be ensured. In fact, the capability approach views people not just as beneficiaries of development, but as the architects of their lives (UNDP, 2002). When people are coerced into an action, submissive or desirous to please or simply passive, they are not exercising agency – a concept related to but distinct from wellbeing.

Agency is fundamentally linked to truly functional, participatory democracy. Much broader than just the voting process, it leads to a virtuous cycle. Political freedoms empower people to demand policies that expand their opportunities to hold governments accountable. Debate and discussion help communities to shape their priorities. A free press, a vibrant civil society and the political freedoms guaranteed by a constitution underpin inclusive institutions and human development.

Introducing the DCI

Building on these ideas, the proposed DCI measures shortfalls in three development achievements: basic wellbeing freedoms as measured by the three quality-adjusted dimensions of the traditional HDI; environmental sustainability; and good governance (see Abu-Ismail et al, 2022).

In line with the normative position that these challenges are intrinsically of equal importance, each of the challenges and their dimensions are awarded an equal weight. To maintain simplicity, the report’s authors used an arithmetic average rather than a geometric one. There are good reasons for doing so when many indicators are involved. This also leads to an index that is easy to compute and interpret.

Framework for the DCI’s three sets of challenges to development

Note: Dimension and sub-dimension weights are in parenthesis

The DCI makes an important shift from development achievements to development challenges. This reverses the narrative to foreground countries that are most rather than least challenged, which helps to draw attention to them in the global discussion on human development and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Scores on the DCI and its components are distributed among five categories: very low, low, medium, high and very high challenges. Country scores up to 0.2 denote the very low challenge category. Scores from 0.2-0.299 are the low challenge category. Scores from 0.3-0.449 are in the medium challenge group while scores from 0.455-0.5499 are at the high challenge level. Scores above 0.55 mark the very high challenge group.

Main findings of the report

Of the 163 countries assessed by the DCI, 49 face high and 25 face very high development challenges. They are home to nearly 3.5 billion people, or 45% of the world’s population. Only 15 countries with around 5% of the world’s population have very low development challenges. Consistent with the findings of other indices, the most challenged countries measured by the DCI are mainly in sub-Saharan Africa. The least challenged are mainly in Europe.

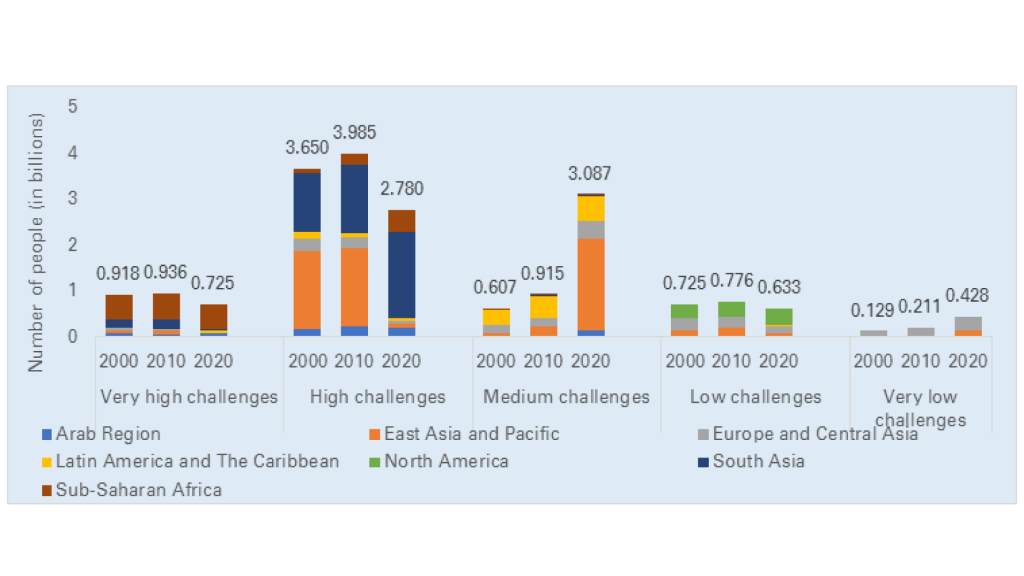

The graduation of East Asia and the Pacific from the high challenge group to the medium challenge group resulted in a significant drop in the share of the world’s population in the former category, from 60% in 2000 to 36% in 2020 (see Figure 1). Without gains made by this region, specifically by China, the world’s DCI picture in 2020 would look nearly identical to that of 2000, given little movement in the very high to high challenge groups. The very high challenge countries in 2020 are essentially the same as in 2000.

At the country level, Haiti ranked highest in DCI worldwide at 0.658, while Switzerland ranked lowest at 0.124. This shows that even the least challenged country still has room for improvement.

Countries with the largest deteriorations in DCI between 2000 and 2020 are mainly in the Arab region and in Latin America and the Caribbean. Several of these countries have confronted domestic or regional conflict. Countries with the greatest improvements on DCI, such as Rwanda, had recovered from severe deprivations since 2000. Post-Soviet countries, including Azerbaijan, Georgia and Uzbekistan, have also made substantial improvements over the past two decades.

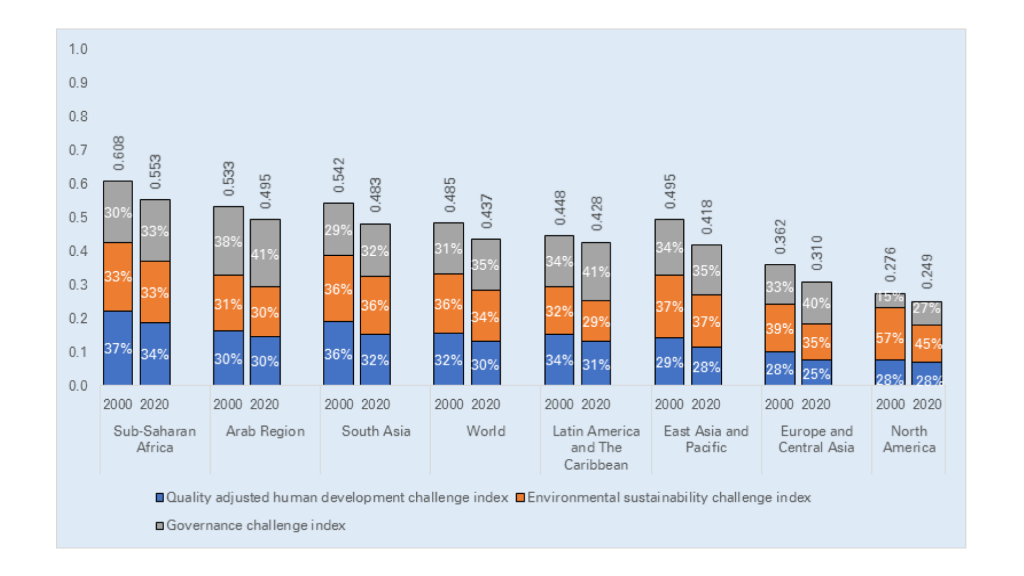

When considering the share of each of the three challenges in the DCI scores, a distinct regional pattern emerges. Environmental sustainability or governance challenges make up the highest shares in most regions except sub-Saharan Africa, where quality-adjusted human development challenges are greater.

Globally, given a significant rise in governance challenges over the past two decades, by 2020 the governance dimension comprised 35% of the global DCI score. But the relative equal share of each dimension at the global level and for developing regions lends support to our conceptual framework in treating them as equally important.

Figure 1: Population in each DCI category by region, 2000, 2010 and 2020

Source: ESCWA, 2022

No region has a very low quality-adjusted human development challenge index (see Figure 2). This means there is still much to be achieved on core human development dimensions, even in the two most developed regions of the world: Europe and North America. Similar to other regions, the Arab region is particularly challenged in education, with the quality-adjusted education component contributing to nearly half of the quality-adjusted human development challenge index.

Global governance challenges increased over the period from 2000 to 2020. The overall increase is largely due to greater democratic governance challenges in most regions. The Arab region faces the highest governance challenge and thus has the highest score on the democratic governance challenge dimension.

Figure 2: DCI regional scores and shares of the three challenges, 2000 and 2020

Source: ESCWA, 2022

Policy implications

- Although the Covid-19 pandemic caused new institutional challenges, it has pressured countries to act swiftly amid increased uncertainty. Rapid changes in lifestyle and increases in non-communicable diseases have widened the gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy. Improving healthy life outcomes depends on protecting the health of environmental systems, which can only happen by adopting new technologies and by changing prevailing consumption patterns. Countries must therefore shift to more sustainable economic growth models that work for both the people and the planet.

- Governments should focus on developing well-rounded and integrated educational systems that reach young men and women in all regions of a country, including the most vulnerable people in rural areas. Subsidies and scholarship programmes allow more students to complete their education and enter the labour market with required skills. This should also be matched with macroeconomic policies that aim to encourage decent job creation in order to preserve and reinforce the relationship between high-quality education, decent employment and the reduction of poverty and inequality.

- When rethinking human development measurement, it is imperative to recognise that without effective institutions, wellbeing cannot be ensured or sustained. At the same time, wellbeing is not a substitute for agency. Both agency and wellbeing are essential aspects of human development. Strong institutions should ensure that government effectiveness and democratic principles operate in a virtuous nexus. By the same token, democratic governance without quality public services is also not a solution. Governments must therefore aim to advance both democracy and effectiveness.

- Human development and conflict are highly interlinked and directly connected to wellbeing and agency. Lower risks of conflict are more likely where policies create institutional and governance reform plans, close gaps between formal and actual rights, strengthen civil society’s capacity to hold dialogues with the authorities, develop strong political checks to protect accountability, and raise awareness of the importance of accountability in building public trust and confidence. Therefore, good governance and respect for human rights and basic freedoms are vital to ending conflict.

- Resolving the world’s development challenges requires focusing first on the highly challenged countries. They face multifaceted challenges, and lag in all dimensions of quality-adjusted human development, environmental sustainability and governance. To provide support to these countries, the global community should implement measures similar to those provided to the least developed countries, including international tax cooperation to reduce tax evasion from multinational companies and to set standard wages to avoid inequalities.

- To ensure that no one is left behind, the emphasis should be on a deep understanding of threats, risks and crises, and of the interlinkages between human development and human security. To that end, countering the shock-driven response to global threats and promoting a culture of prevention are of utmost importance.

Further reading

Abu-Ismail, K, V Hlasny, A Jaafar and others (2022) Development challenges index: statistical measurement and validity, ESCWA.

ESCWA, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (2022) World Development Challenges Report: Development from a broader lens.

Jahan, S (2022) Rethinking Human Development: Concepts and Measurements, ESCWA.

McKinley, T (2016) The Need for a New Framework for Defining a Development Measure for the Arab Countries, ESCWA.

Sen, A, and S Anand (1994) ‘Sustainable Human Development: Concepts and Priorities’, Human Development Report Office Occasional Paper #8.

UNDP, United Nations Development Programme (2002) Human Development Report.